Taphonomic observation of faunal remains from the Gezishan Locality 10 in Ningxia Hui Autonomous Region

Received date: 2018-08-16

Revised date: 2019-02-13

Online published: 2020-09-10

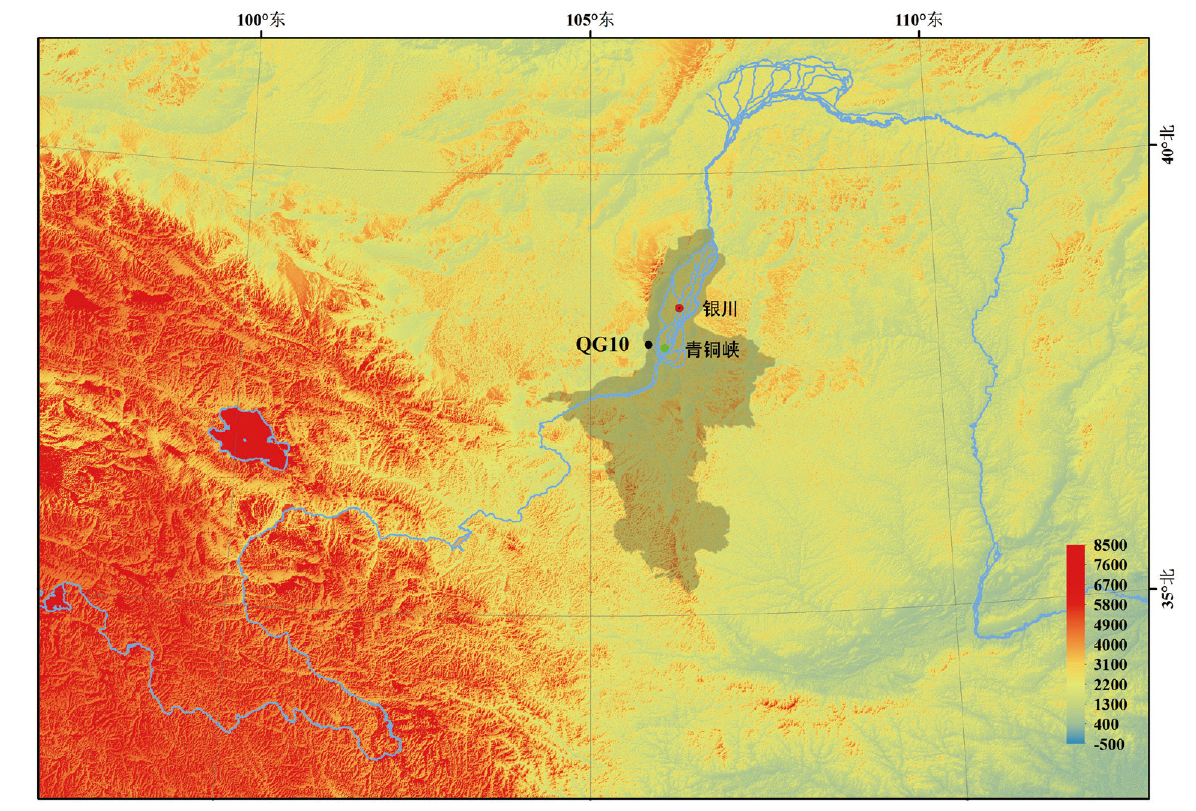

Located in the foothills of Helan Mountain, roughly 20 km to the northwest of Qingtongxia City, locality 10(QG10) of the Gezishan site was systematically excavated in 2014-2017. Along with thousands of lithic tools of microblade technology and dozens of perforated beads and bone artifacts, a large number of faunal remains was recovered from the site. Based on preliminary observations of taphonomic features of the animal bones identifiable to a specific taxon and/or skeletal element from the site, it could be argued that humans are the main agent responsible for the accumulation and modification of the faunal remains at QG10, and they procured the main prey animals through active hunting rather than aggressive scavenging. In addition, hunter-gatherers transported complete carcasses to the site to be processed, butchering the middle/large-sized animals and breaking open their bones mainly for nutritional purposes. However, it seems clear that in addition to their nutritional value, small animals at the site were probably exploited to manufacture bone artifacts as well.

Key words: Gezishan site; Taphonomy; Zooarchaeology; Paleolithic; Adaptive strategy

Shuangquan ZHANG , Fei PENG , Yue ZHANG , Jialong GUO , Huimin WANG , Chao HUANG , Jingwen DAI , Yuzhe ZHANG , Xing GAO . Taphonomic observation of faunal remains from the Gezishan Locality 10 in Ningxia Hui Autonomous Region[J]. Acta Anthropologica Sinica, 2019 , 38(02) : 232 -244 . DOI: 10.16359/j.cnki.cn11-1963/q.2019.0019

| [1] | 彭菲, 郭家龙, 王惠民, 等. 宁夏鸽子山遗址再获重大发现[J]. 中国文物报, 2017 -02-10(第5版) |

| [2] | 张乐, 王春雪, 张双权, 等. 切割痕迹揭示马鞍山遗址晚更新世末人类肉食行为[J]. 科学通报, 2009,54:2871-2878 |

| [3] | Norton CJ, 张双权, 张乐, 等.上/更新世动物群中人类与食肉动物“印记”的识别[J]. 人类学学报, 2007,26:183-192 |

| [4] | Lyman RL. Vertebrate Taphonomy[M]. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1994: 1-552 |

| [5] | Norton CJ, Gao X. Hominin-carnivore interactions during the Chinese Early Paleolithic: Taphonomic perspectives from Xujiayao[J]. Journal Of Human Evolution, 2008,55(1):164-178 |

| [6] | Blumenschine RJ, Marean CW, Capaldo SD. Blind tests of inter-analyst correspondence and accuracy in the identification of cut marks, percussion marks, and carnivore tooth marks on bone surfaces[J]. Journal of Archaeological Science, 1996,23(4):493-507 |

| [7] | Blumenschine RJ. Percussion marks, tooth marks, and experimental determinations of the timing of hominid and carnivore access to long bones at FLK Zinjanthropus, Olduvai Gorge, Tanzania[J]. Journal Of Human Evolution, 1995,29(1):21-51 |

| [8] | Dominguez-Rodrigo M. Flesh availability and bone modifications in carcasses consumed by lions: Palaeoecological relevance in hominid foraging patterns[J]. Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology, 1999,149(1-4):373-388 |

| [9] | Dominguez-Rodrigo M, Barba R. New estimates of tooth mark and percussion mark frequencies at the FLK Zinj site: The carnivore-hominid-carnivore hypojournal falsified[J]. Journal Of Human Evolution, 2006,50(2):170-194 |

| [10] | Zhang Y, Stiner MC, Dennell R, et al. Zooarchaeological perspectives on the Chinese Early and Late Paleolithic from the Ma’anshan site(Guizhou, South China)[J]. Journal of Archaeological Science, 2010,37(8):2066-2077 |

| [11] | Stiner MC, Barkai R, Gopher A. Cooperative hunting and meat sharing 400-200 kya at Qesem Cave, Israel[J]. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 2009,106(32):13207-13212 |

| [12] | Fisher JW. Bone surface modifications in zooarchaeology[J]. Journal of Archaeological Method and Theory, 1995,2(1):7-68 |

| [13] | Brain CK. The Hunters or the Hunted? An Introduction to African Cave Taphonomy[M]. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1981: 1-384 |

| [14] | Capaldo SD, Blumenschine RJ. A quantitative diagnosis of notches made by hammerstone percussion and carnivore gnawing in bovid long bones[J]. American Antiquity, 1994,59(4):724-748 |

| [15] | Bunn HT, Kroll EM, Ambrose SH, et al. Systematic Butchery by Plio/Pleistocene Hominids at Olduvai Gorge, Tanzania[and Comments and Reply][J]. Current Anthropology, 1986,27(5):431-452 |

| [16] | Blumenschine RJ, Selvaggio MM. Percussion marks on bone surfaces as a new diagnostic of hominid behaviour[J]. Nature, 1988,333(6175):763-765 |

| [17] | 张双权. 旧石器遗址动物骨骼表面非人工痕迹研究及其考古学意义[J]. 第四纪研究, 2014,34:131-140 |

| [18] | 张双权, 李占扬, 张乐, 等. 河南灵井许昌人遗址动物骨骼表面人工改造痕迹[J]. 人类学学报, 2011,30:313-326 |

| [19] | Haynes G. A guide for differentiating mammalian carnivore taxa responsible for gnaw damage to herbivore limb bones[J]. Paleobiology, 1983: 164-172 |

| [20] | Binford LR. Bones: Ancient Men and Modern Myth[M]. New York: Academic Press, 1981: 1~ 320 |

| [21] | Olsen SL, Shipman P. Surface modification on bone: Trampling versus butchery[J]. Journal of Archaeological Science, 1988,15(5):535-553 |

| [22] | Fiorillo AR. An introduction to the identification of trample marks[J]. Current Research in the Pleistocene, 1984,1:47-48 |

| [23] | Behrensmeyer AK, Gordon KD, Yanagi GT. Nonhuman bone modification in Miocene fossils from Pakistan[A]. In: Bonnichsen R, Sorg M, eds. Bone Modification[C]. Orono: Center for the Study of the First Americans, 1989, 99-120 |

| [24] | Hill A. Bone Modification by Modem Spotted Hyenas[A]. In: Bonnichsen R, Sorg MH, eds. Bone Modification[C]. Orono: University of Maine Center for the Study of the First Americans, 1989, 169-178 |

| [25] | Nilssen PJ. An actualistic butchery study in South Africa and its implications for reconstructing hominid strategies of carcass acquisition and butchery in the Upper Pleistocene and Plio-Pleistocene[D]. Ph.D Dissertation. Cape Town: University of Cape Town, 2000 |

| [26] | Behrensmeyer AK. Taphonomic and ecologic information from bone weathering[J]. Paleobiology, 1978,4(2):150-162 |

| [27] | Selvaggio MM. Carnivore tooth marks and stone tool butchery marks on scavenged bones—archaeological implications[J]. Journal Of Human Evolution, 1994,27(1-3):215-228 |

| [28] | Capaldo SD. Experimental determinations of carcass processing by Plio-Pleistocene hominids and carnivores at FLK 22(Zinjanthropus), Olduvai Gorge, Tanzania[J]. Journal Of Human Evolution, 1997,33(5):555-597 |

| [29] | Norton CJ, Gao X. Zhoukoudian Upper Cave revisited[J]. Current Anthropology, 2008,49(4):732-745 |

| [30] | Parkinson JA, Plummer T, Hartstone-Rose A. Characterizing felid tooth marking and gross bone damage patterns using GIS image analysis: An experimental feeding study with large felids[J]. Journal Of Human Evolution, 2015,80:114-134 |

| [31] | Faith JT. Sources of variation in carnivore tooth-mark frequencies in a modern spotted hyena(Crocuta crocuta) den assemblage, Amboseli Park, Kenya[J]. Journal of Archaeological Science, 2007,34(10):1601-1609 |

| [32] | Blumenschine RJ, Prassack KA, Kreger CD, et al. Carnivore tooth-marks, microbial bioerosion, and the invalidation of Dominguez-Rodrigo and Barba’s(2006) test of Oldowan hominin scavenging behavior[J]. Journal Of Human Evolution, 2007,53(4):420-426 |

| [33] | Dominguez-Rodrigo M. Meat-eating by early hominids at the FLK 22 Zinjanthropus site, Olduvai Gorge(Tanzania): An experimental approach using cut-mark data[J]. Journal Of Human Evolution, 1997,33(6):669-690 |

| [34] | Lupo KD, O’Connell JF. Cut and tooth mark distributions on large animal bones: Ethnoarchaeological data from the Hadza and their implications for current ideas about early human carnivory[J]. Journal of Archaeological Science, 2002,29(1):85-109 |

| [35] | Zhang Y, Zhang SQ, Xu X, et al. Zooarchaeological perspective on the Broad Spectrum Revolution in the Pleistocene-Holocene transitional period, with evidence from Shuidonggou Locality 12, China[J]. Science China: Earth Sciences, 2013,56(9):1487-1492 |

| [36] | Zeder MA. The Broad Spectrum Revolution at 40: Resource diversity, intensification, and an alternative to optimal foraging explanations[J]. Journal Of Anthropological Archaeology, 2012,31(3):241-264 |

| [37] | Prendergast ME, Yuan JR, Bar-Yosef O. Resource intensification in the Late Upper Paleolithic: A view from southern China[J]. Journal of Archaeological Science, 2009,36(4):1027-1037 |

| [38] | Munro ND. Epipaleolithic subsistence intensification in the Southern Levant: The faunal evidence[A]. In: Hublin J-J, Richards MP, eds. Evolution of Hominin Diets: Integrating approaches to the study of palaeolithic subsistence, 2009, 141-155 |

| [39] | Stiner MC. Thirty years on the “Broad Spectrum Revolution” and paleolithic demography[J]. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA, 2001,98(13):6993-6996 |

| [40] | Stiner MC, Munro ND, Surovell TA. The Tortoise and the Hare: Small-Game Use, the Broad-Spectrum Revolution, and Paleolithic Demography[J]. Current Anthropology, 2000,41(1):39-79 |

| [41] | Zhang Y, Wang CX, Zhang SQ, et al. A zooarchaeological study of bone assemblages from the Ma’anshan Paleolithic site[J]. Science China: Earth Sciences, 2010,53(3):395-402 |

| [42] | Zhang S, Zhang Y, Li J, et al. The broad-spectrum adaptations of hominins in the later period of Late Pleistocene of China—Perspectives from the zooarchaeological studies[J]. Science China Earth Sciences, 2016,59(8):1529-1539 |

| [43] | Pickering TR, Egeland CP. Experimental patterns of hammerstone percussion damage on bones: Implications for inferences of carcass processing by humans[J]. Journal of Archaeological Science, 2006,33(4):459-469 |

| [44] | Bar-Oz G, Adler DS. Taphonomic History of the Middle and Upper Palaeolithic Faunal Assemblage from Ortvale Klde , Georgian Republic[J]. Journal of Taphonomy, 2005,3(4):185-211 |

| [45] | 张双权. 河南许昌灵井动物群的埋藏学研究[D].博士学位论文. 北京: 中国科学院古脊椎动物与古人类研究所, 2009 |

| [46] | 张乐. 马鞍山遗址古人类行为的动物考古学研究[D].博士学位论文. 北京: 中国科学院研究生院, 2008 |

| [47] | Shipman P, Foster G, Schoeninger M. Burnt bones and teeth: An experimental study of color, morphology, crystal structure and shrinkage[J]. Journal of Archaeological Science, 1984,11(4):307-325 |

| [48] | Stiner MC, Kuhn SL, Weiner S, et al. Differential Burning, Recrystallization, and Fragmentation of Archaeological Bone[J]. Journal of Archaeological Science, 1995,22(2):223-237 |

| [49] | Hanson M, Cain. CR. Examining histology to identify burned bone[J]. Journal of Archaeological Science, 2007,34(11):1902-1913 |

| [50] | Gifford-Gonzalez DP. Ethnographic analogues for interpreting modified bones: Some cases from East African[A]. In: Bonnichsen R, Sorg MH, eds. Bone Modification[C]. Orono: University of Maine Center for the Study of the First Americans, 1989, 179-246 |

| [51] | Gifford DP. Taphonomy and paleoecology: A critical review of archaeology’s sister disciplines[A]. In: Schiffer MB, ed. Advances in Archaeological Method and Theory[C]. New York and London: Academic Press, 1981, 365-438 |

| [52] | Johnson E. Current developments in bone technology[A]. In: Schiffer MB, ed. Advances in Archaeological Method and Theory[C]. New York and London: Academic Press, 1985, 157-235. |

| [53] | Bunn HT. Comparative analysis of modern bone assemblages from a San hunter-gatherer camp in the Kalahari Desert, Botswana, and from a spotted hyena den near Nairobi, Kenya[A]. In: Clutton-Brock J, Grigson C, eds. Animals and Archaeology: 1 Hunters and Their Prey [C]. Oxford: British Archaeological Reports(International Series), 1983, 143-148 |

| [54] | Villa P, Mahieu E. Breakage patterns of human long bones[J]. Journal Of Human Evolution, 1991,21(1):27-48 |

| [55] | Bunn HT, III. Meat-eating and human evolution: Studies on the diet and subsistence patterns of Plio-Pleistocene hominids in East Africa[D]. Ph.D Dissertation. California: University of California, 1982 |

| [56] | Binford LR. Nunamiut Ethnoarchaeology[M]. New York: Academic Press, 1978: 1-509 |

| [57] | Bartram LE. Perspectives on skeletal part profiles and utility curves from eastern Kalahari ethnoarchaeology[A]. In: Hudson J, ed. From bones to behavior: Ethnoarchaeological and experimental contributions to the interpretation of faunal remains[C]. Carbondale: Center for Archaeological Investigations at Southern Illinois University, 1993, 115-137 |

| [58] | Bartram LE. Perspectives on skeletal part profiles and utility curves from Eastern Kalahari ethnoarchaeology[A]. In: Hudson J, ed. From Bones to Behavior: Ethnoarchaeological and Experimental Contributions to the Interpretations of Faunal Remains[C]. Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press, 1993, 115-137 |

| [59] | Bunn HT, Bartram LE, Kroll EM. Variability in bone assemblage formation from Hadza hunting, scavenging, and carcass processing[J]. Journal Of Anthropological Archaeology, 1988,7(4):412-457 |

| [60] | White TE. Observations on the butchering technique of some aboriginal people(1)[J]. American Antiquity, 1952,17(3):337— 338 |

| [61] | Metcalfe D, Jones KT. A reconsideration of animal body-part utility indices[J]. American Antiquity, 1988,53(3):486-504 |

| [62] | Grayson DK. Quantitative Zooarchaeology: Topics in the Analysis of Archaeological Faunas[M]. Massachusetts: Academic Press, 1984 |

| [63] | Lyman RL. Quantitative Paleozoology[M]. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2008 |

| [64] | Lam YM, Chen Xb, Pearson OM. Intertaxonomic varibility in patterns of bone density and the differential representation of Bovid, Cervid, and Equid elements in the Archaeological record[J]. American Antiquity, 1999,64(2):343-362 |

| [65] | Klein RG, Cruz-Uribe K. The Analysis of Animal Bones from Archaeological Sites[M]. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1984 |

| [66] | Klein RG, Wolf C, Freeman LG, et al. The use of dental crown heights for constructing age profiles of red deer and similar species in archaeological samples[J]. Journal of Archaeological Science, 1981,8(1):1-31 |

| [67] | Hillson S. Teeth[M]. 2nd ed. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2005 |

| [68] | Levine MA. Archaeo-Zoological Analysis of Some Upper Pleistocene Horse Bone Assemblages in Western Europe[D]. Ph.D dissertation. Cambridge: University of Cambridge, 1979 |

| [69] | Spinage CA. Age estimation of zebra[J]. East African Wildlife Journal, 1972,10:273-277 |

/

| 〈 |

|

〉 |