The incisive canal position of the Chinese Pleistocene humans and its evolutionary implications

Received date: 2020-02-08

Revised date: 2020-04-10

Online published: 2020-09-11

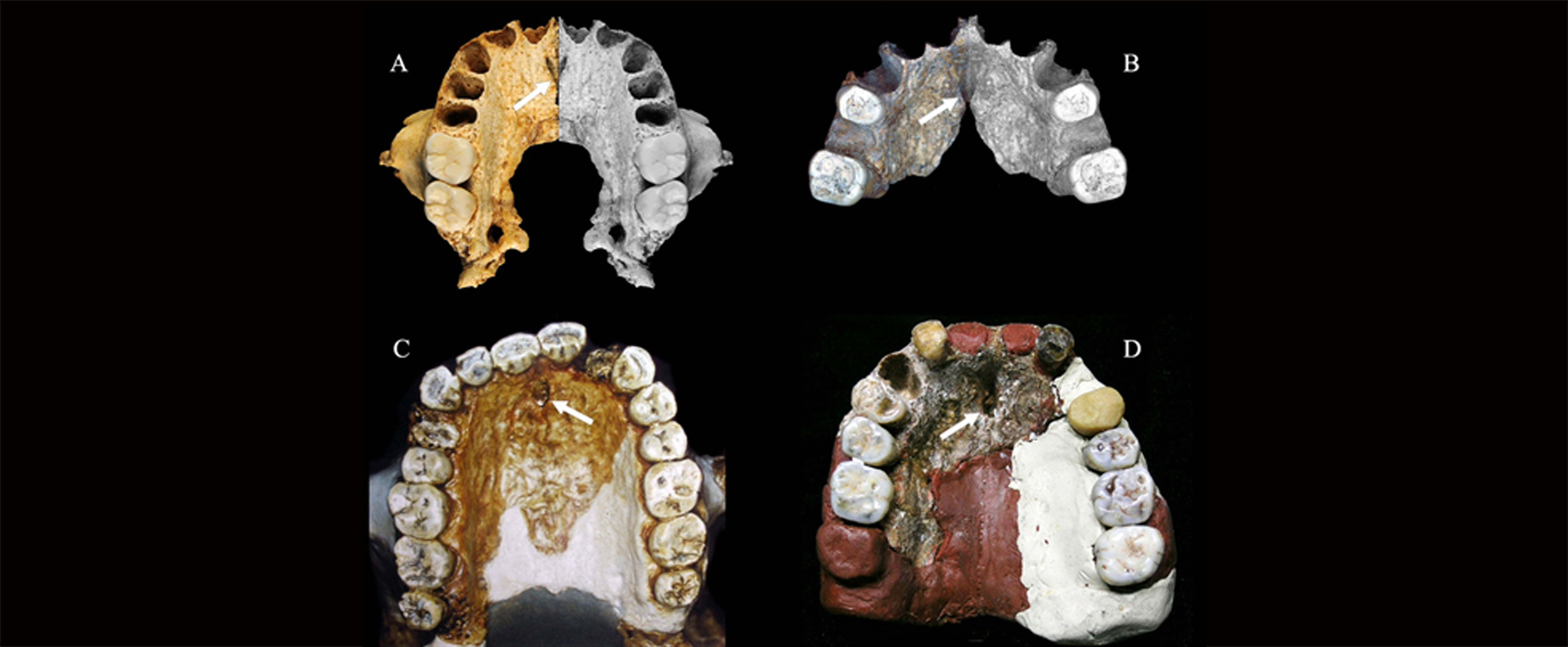

When studying the fossils of Homo erectus from Zhoukoudian, Weidenreich pointed out that the incisive foramen is more posteriorly positioned compared with that of modern humans in which the foramen is situated anteriorly more close to alveolar border. Since then, incisive foramen have been used in paleoanthroology studies as an indicator with evolutionary value. However, till now, only one Chinese human fossil from Zhoukoudian was studied for the position of incisive foramen while no study of incisive foramen positions in modern Chinese has been conducted. In this study, the positions of incisive foramen of Chinese human fossils and specimens of modern Chinese population were observed and measured. Based on these, in conjunction with previous studies of incisive foramen of human fossils around the world, the expression pattern and evolutionary implications of the incisive foramen positions for Chinese human fossils were explored. Our study indicates that from Early Pleistocene to Late Pleistocene, the positions of incisive foramens in Chinese human fossils follow the trend to the anterior positions. The positions of incisive foramens in Early and Middle Pleistocene Homo erectus (Yunxian and Zhoukoudian) are more posteriorly positioned; In late Middle Pleistocene, the positions of incisive foramens in some specimens (Dali, Changyang, Hualongdong) are moved forwardly resembling those of modern humans, while other specimens (Jinniushan, Chaoxian) exhibit posteriorly positioned incisive foramens, which are within the variation ranges of Homo erectus; In all the specimens of Late Pleistocene humans, the positions of incisive foramens situate anteriorly within the variation ranges of modern humans. The investigation of the incisive foramen in modern Chinese population show that although the positions in modern humans are anterior, the size and shape of the incisive foramens in modern humans exhibit pronounced variabilities. This expression pattern of the incisive foramens in modern humans will affect the evaluations to the position and evolutionary implications of the incisive foramens. In additions, nearly all the incisive foramens in modern human specimens are open in their anterior borders and the incisive canals take inclined trends towards superoposterior directions from the entrance. This discovery is different from the vertical direction of the incisive canals in modern humans proposed by Weidenreich. In considering the investigated data of the incisive foramens in Chinese human fossils, modern Chinese specimens and incisive foramen positions of other human fossils around the world, the authors believe that the positions of incisive foramens exhibit relatively fixed pattern in the human evolution and posteriorly positioned incisive foramens should be treated as a primitive traits.

Key words: Incisive canal; Fossil humans in China; Modern humans; Human evolution

Wu LIU , Jiaming HUI , Jianing HE , Xiujie WU . The incisive canal position of the Chinese Pleistocene humans and its evolutionary implications[J]. Acta Anthropologica Sinica, 2021 , 40(05) : 739 -750 . DOI: 10.16359/j.cnki.cn11-1963/q.2020.0015

| [1] | White T. Human Osteology[M]. New York: Academic Press, 2000, 1-563 |

| [2] | 柏树令, 段坤昌, 陈金宝. 人类解剖学彩色图谱[M]. 上海: 上海科学技术出版社, 2002, 1-267 |

| [3] | Drake RL, Vogl AW, Mitchell AWM. Gray’s Anatomy for Students(2nd Edition)[M]. Philadelphia: Churchill Livingstone Press. 2010, 1-1150 |

| [4] | 杜希哲, 杨玉田. 国人切牙孔和切牙管的观察和测量[J]. 西安医学院学报, 1984, 5:291-294 |

| [5] | 姜陵, 叶凌云. 切牙孔、中切牙及鼻底平面关系观察[J]. 医学研究通讯, 2005, 34:53-54 |

| [6] | 颜冬, 谢宁, 张晗, 等. 切牙管及其与上颌中切牙位置关系的研究进展[J]. 口腔医学, 2019, 39:957-960 |

| [7] | Weidenreich F. The Skull of Sinanthropus pekinensis: A Comparative Study of A Primitive Hominid Skull[M]. Palaeontologica Sinica N.S. D10, The Geological Survey of China, 1943, 1-484 |

| [8] | Rightmire GP. Evidence from facial morphology for similarity of Asian and African representatives of Homo erectus[J]. American Journal of Physical Anthropology, 1998, 106:61-85 |

| [9] | Rightmire GP, Ponce de Leon MS, Lordkipanidze D, et al. Skull 5 from Dmanisi: Descriptive anatomy, comparative studies, and evolutionary significance[J]. Journal of Human Evolution, 2017, 104:50-79 |

| [10] | Rightmire GP. The human cranium from Bodo, Ethiopia: evidence for speciation in the Middle Pleistocene?[J]. Journal of Human Evolution, 1996, 31:21-39 |

| [11] | Arsuaga JL, Martínez I, Lorenzo C, et al. The human cranial remains from Gran Dolina lower Pleistocene site (Sierra de Atapuerca, Spain)[J]. Journal of Human Evolution, 1999, 37:431-457 |

| [12] | Heim JL. Les Hommes Fossiles de La Ferrassie. Tome I. Le gisement, les squelettes adultes (crâne et squelette du tronc). Archives de L’Institut de Paléontologie Humaine, mémoire[J]. 1976, 35:1-331 |

| [13] | Martin H. L’homme fossile de la Quina[M]. Paris: Doin, 1923 |

| [14] | Hershkovitz I, Weber G, Quam R, et al. The earliest modern humans outside Africa[J]. Science, 2018, 359:456-459 |

| [15] | Wu XJ, Pei SW, Cai YJ, et al. Archaic human remains from Hualongdong, China, and Middle Pleistocene human continuity and variation[J]. PNAS, 2019, 116:9820-8924 |

| [16] | 贾兰坡. 长阳人化石及共生的哺乳动物群[J]. 古脊椎动物与古人类, 1957, 1:247-257 |

| [17] | 吴新智. 大荔中更新世人类颅骨[M]. 北京: 科学出版社, 2020 |

| [18] | Liu W, Schepartz L, Xing S, et al. Late Middle Pleistocene hominin teeth from Panxian Dadong, South China[J]. Journal of Human Evolution, 2013, 64:337-355 |

| [19] | Wu XJ, Trinkaus E. The Xujiayao 14 mandibular ramus and Pleistocene Homo mandibular variation[J]. Comptes Rendus Palevol, 2014, 13:333-341 |

| [20] | Xing S, Martinón-Torres M, Bermúdez de Castro JM, et al. Hominin teeth from the early Late Pleistocene site of Xujiayao, Northern China[J]. American Journal of Physical Anthropology, 2015, 156:224-240 |

| [21] | Wu XJ, Bruner M. The endocranial anatomy of Maba 1[J]. American Journal of Physical Anthropology, 2016, 160:633-643 |

| [22] | Li ZY, Wu XJ, Zhou LP, et al. Late Pleistocene archaic human crania from Xuchang, China[J]. Science, 2017, 355:969-972 |

| [23] | Xing S, Martinón-Torres M, Bermúdez de Castro JM. Late Middle Pleistocene hominin teeth from Tongzi, southern China[J]. Journal of Human Evolution, 2019, 130:96-108 |

| [24] | 刘武, 邢松, 吴秀杰. 中更新世晚期以来中国古人类化石形态特征的多样性[J]. 中国科学:地球科学, 2016, 46:906-917 |

| [25] | 刘武, 吴秀杰, 邢松. 更新世中期中国古人类演化区域连续性与多样性的化石证据[J]. 人类学学报, 2019, 38:473-490 |

| [26] | 戴静桃, 李平, 李安, 等. 切牙管与上颌中切牙牙根位置关系的CBCT研究[J]. 中国美容医学, 2014, 23:1904-1908 |

| [27] | 姜滨, 王振常, 鲜军舫. 上颌切牙管解剖及病变的多层螺旋CT 表现[J]. 中国美容医学, 2014, 23:1904-1908 |

| [28] | Song WC, Jo DI, Lee JY, et al. Microanatomy of the incisive canal using three-dimensional reconstruction of micro CT images: An ex vivo study[J]. Oral Surgery, Oral Medicine, Oral Pathology and Endodontology, 108:583-590 |

| [29] | Bornstein MM, Balsiger R, Sendi P, et al. Morphology of the nasopalatine canal and dental implant surgery: A radiographic analysis of 100 consecutive patients using limited cone-beam computed tomography[J]. Clinical Oral Implants Research, 2011, 22:295-301 |

/

| 〈 |

|

〉 |