A study of pollen and fungal spores extracted from the feces of domestic herbivores in China and their implications for human behavior

Received date: 2020-03-01

Revised date: 2020-04-30

Online published: 2020-09-11

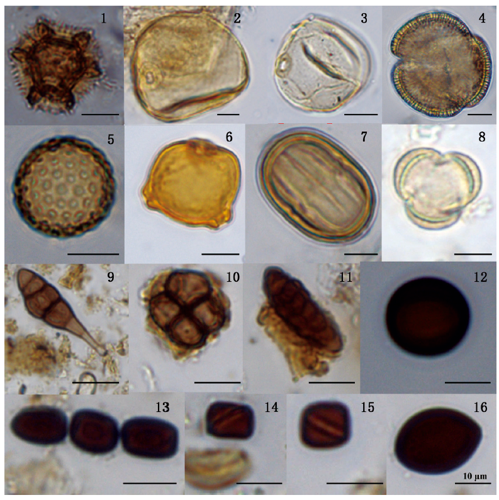

It has been demonstrated that plant microfossils in the coprolites unearthed from archaeological sites are important materials for reconstructing past ecologies and environments as well as human activities. However, the palynological assemblages of animals’ coprolites that reflects human behavior of feeding and grazing are still poorly understood. Here we present the results of a study of the major pollen and fungal spore types found in the feces of six common domestic herbivores in China: goat (Capra aegagrus), sheep (Ovis aries), cattle (Bos taurus), camel (Camelus sp.), yak (Bos grunniens), and horse (Equus caballus). A study of surface soil samples in proximity to a sheepfold was also conducted to evaluate the influence of factors affecting the transmission of coprophilous fungal spores. The pollen characteristics of the feces include overall low taxonomic abundance and a high proportion of just a few pollen types, such as those of the Poaceae and Chenopodiaceae, which are affected by human activities. The main fungal spore types detected in domestic herbivore feces include the genera Sporormiella, Sodaria, Pleospora, Coniochaeta, Thecaphora and Dictyosporium. The distribution of fungal spores is apparently affected by the range of the animals, making it possible to use coprophilous spores (e.g., Sporormiella) to reconstruct the pastoral and animal breeding activities of ancient humans.

Key words: goat; sheep; fungal spores; Sporormiella; paleoecology

Yaping ZHANG , Keliang ZHAO , Xinying ZHOU , Qingjiang YANG , Weiming JIA , Xiaoqiang LI . A study of pollen and fungal spores extracted from the feces of domestic herbivores in China and their implications for human behavior[J]. Acta Anthropologica Sinica, 2021 , 40(05) : 879 -887 . DOI: 10.16359/j.cnki.cn11-1963/q.2020.0026

| [1] | Rasmussen P. Analysis of goat sheep feces from egolzwil-3, switzerland-evidence for branch and twig foddering of livestock in the neolithic[J]. Journal of archaeological science, 1993, 20:479-502 |

| [2] | Harrison T. Paleontology and Geology of Laetoli: Human Evolution in Context[M]. Springer Dordrecht Heidelberg London New York, 2011: 279-292 |

| [3] | Wood JR, Wilmshurst JM, Wagstaff SJ, et al. High-resolution coproecology: Using coprolites to reconstruct the habits and habitats of New Zealand’s extinct upland moa (Megalapteryx didinus)[J]. PloS ONE, 2012, doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0040025 |

| [4] | Gil-Romera G, Neumann FH, Scott L, et al. Pollen taphonomy from hyaena scats and coprolites: preservation and quantitative differences[J]. Journal of Archaeological Science, 2014, 46:89-95 |

| [5] | 王文娟, 吴妍, 宋国定, 等. 灵井许昌人遗址鬣狗粪化石的孢粉和真菌孢子研究[J]. 科学通报, 2013, 58:51-56 |

| [6] | Geel BV, Buurman J, Brinkkemper O, et al. Environmental reconstruction of a Roman Period settlement site in Uitgeest (The Netherlands), with special reference to coprophilous fungi[J]. Journal of Archaeological Science. 2003, 7:873-883 |

| [7] | Scott L. Pollen analysis of hyena coprolites and sediments from Equus Cave, Taung, southern Kalahari (South Africa)[J]. Quaternary Research, 1987, 28:144-156 |

| [8] | Carrión JS, Riquelme JA, Navarro C. Pollen in hyaena coprolites reflects late glacial landscape in southern Spain[J]. Palaeogeography Palaeoclimatology Palaeoecology. 2001, 176:0-205 |

| [9] | López-Sáez JA, López-Merino L. Coprophilous fungi as a source of information of anthropic activities during the Prehistory in the Amblés Valley(Ávila, Spain): The archaeopalynological record[J]. Revista Espanola de Micropaleontologia, 2007, 39(1-2):103-116 |

| [10] | Ejarque A, Miras Y, Riera S. Pollen and non-pollen palynomorph indicators of vegetation and highland grazing activities obtained from modern surface and dung datasets in the eastern Pyrenees[J]. Review of Palaeobotany and Palynology, 2011, 167:123-139 |

| [11] | Graves SS, Burner AW, Edwards JW, et al. Dynamic Deformation Measurements of an Aeroelastic Semispan Model[J]. Journal of Aircraft, 2003, 40:977-984 |

| [12] | Zhang YN, Geel BV, Gosling WD, et al. Local vegetation patterns of a Neolithic environment at the site of Tianluoshan, China, based on coprolite analysis[J]. Review of Palaeobotany and Palynology, 2019, 271 |

| [13] | Mazier F, Galop D, Gaillard MJ, et al. Multidisciplinary approach to reconstructing local pastoral activities: An example from the Pyrenean Mountains (Pays Basque)[J]. The Holocene, 2009, 19:171-188 |

| [14] | Cugny C, Mazier F, Galop D. Modern and fossil non-pollen palynomorphs from the Basque mountains (western Pyrenees, France): the use of coprophilous fungi to reconstruct pastoral activity[J]. Vegetation History and Archaeobotany, 2010, 19:391-408 |

| [15] | 刘炳仑. 粪便孢粉学[J]. 化石, 1993(4):26-26 |

| [16] | 吴玉书, 于浅黎. 粪化石中的孢粉[J]. 化石, 1981(3):19-20 |

| [17] | 杜乃秋, 于浅黎. 周口店鬣狗(Hyaena)粪化石的孢粉分析[J]. 古脊椎动物学报, 1980 (3):83 |

| [18] | 郝瑞辉, 萧家仪, 房迎, 等. 南京汤山驼子洞鬣狗粪化石的孢粉分析[J]. 古生物学, 2008, 47(1):123-138 |

| [19] | 郝秀东, 翁成郁. 粪生真菌孢子在古生态学研究中的指示意义[J]. 海洋地质与第四纪地质, 2015, 35(1):175-184 |

| [20] | Wei HC, Hou GL, Fan QS, et al. Using coprophilous fungi to reconstruct the history of pastoralism in the Qinghai Lake Basin, Northeastern Qinghai-Tibetan Plateau[J]. Progress in Physical Geography: Earth and Environment, 2019, 44(1):030913331986959 |

| [21] | Huang XZ, Zhang J, Storozum M, et al. Long-term herbivore population dynamics in the northeastern Qinghai-Tibetan Plateau and its implications for early human impacts[J]. Review of Palaeobotany and Palynology, 2020, 275:104171 |

| [22] | Moore PD, Webb JA. An illustrated Guide to pollen analysis[M]. New York: Wiley, 1978: 1-133 |

| [23] | 李小强, 杜乃秋. 第四纪花粉的无酸碱分析法[J]. 植物学报, 1999, 41(7):782-784 |

| [24] | 唐领余, 毛礼米, 舒军武. 中国第四纪孢粉图鉴[M]. 北京: 科学出版社, 2016: 1-602 |

| [25] | 王伏雄, 钱南芬, 张玉龙, 等. 中国植物花粉形态(第二版)[M]. 北京: 科学出版社, 1997, 1-461 |

| [26] | 席以珍, 宁建长. 中国干旱半干旱地区花粉形态研究[J]. 玉山生物学报, 1994, 11:119-191 |

| [27] | Taylor, Thomas N. Fossil Fungi[M]. New York: Academic Press, 1988 |

| [28] | Andr A, Geel BV . Fungi of the colon of the Yukagir Mammoth and from stratigraphically related permafrost samples[J]. Review of Palaeobotany & Palynology, 2006, 141:225-230 |

| [29] | Grimm EC. Tilia and Tilia. GRAPH. PC spread sheet and graphics software for pollen data. INQUA, Working Group in Data Handling methods[J]. Newsletter, 1990(4):5-7 |

| [30] | Grimm EC. Tilia version 2.0[CP/OL]. Illinois State Museum, Research and Collections Center, 1991-1993. URL: https://www.tiliait.com/download/ |

| [31] | Carrión JS. A taphonomic study of modern pollen assemblages from dung and surface sediments in arid environments of Spain[J]. Review of Palaeobotany and Palynology, 2002, 120:217-232 |

| [32] | 张新时. 中国植被及其地理格局(2)[M]. 北京: 地质出版社, 2007 |

| [33] | 许清海, 李月丛, 阳小兰, 等. 北方草原区主要群落类型表土花粉分析[J]. 地理研究, 2005(3):394-402 |

| [34] | 邵孔兰, 张健平, 丛德新, 等. 植物微体化石分析揭示阿敦乔鲁遗址古人生存策略[J]. 第四纪研究, 2019, 39(1):37-47 |

| [35] | Caretta G, Piontelli E, Savino E. Some coprophilous fungi from Kenya[J]. Mycopathologia, 1998, 142:125-134 |

| [36] | 赵雪琴, 李宜垠, 杨柳, 等. 食草动物粪便中的真菌孢子-粪壳菌及其在第四纪环境研究中的意义[J]. 第四纪研究, 2013, 33(3) : 613-614 |

| [37] | Ahmed SI, Cain RF. Revision of the genera Sporormia and Sporormiella[J]. Canadian Journal of Botany, 1972, 50:419-477 |

| [38] | Owen D, David S. Sporormiella fungal spores, a palynological means of detecting herbivore density[J]. Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology. 2006, 237:40-50 |

| [39] | Feranec RS, Miller NG, Lothrop JC, et al. The Sporormiella proxy and end-Pleistocene megafaunal extinction: A perspective[J]. Quaternary International, 2011, 245:333-338 |

| [40] | Baker AG, Cornelissen P, Bhagwat SA, et al. Quantification of population sizes of large herbivores and their long-term functional role in ecosystems using dung fungal spores[J]. Methods Ecological Evolution, 2016, 7(11):1273-1281 |

| [41] | Gill JL, Mclauchlan KK, Skibbe AM, et al. Linking abundances of the dung fungus Sporormiella to the density of bison: Implications for assessing grazing by megaherbivores in palaeorecords[J]. Journal of Ecology, 2013, 101(5):1125-1136 |

| [42] | Chepstow AJ, Frogley MR, Baker AS. Comparison of Sporormiella dung fungal spores and oribatid mites as indicators of large herbivore presence: evidence from the Cuzco region of Peru[J]. Archaeology Science, 2019, 102:61-70 |

| [43] | Gauthier E, Bichet V, Massa C, et al. Pollen and non-pollen palynomorph evidence of medieval farming activities in southwestern Greenland[J]. Vegetation History and Archaeobotany, 2010, 19(5-6): 427-438.2 |

| [44] | Finsinger W, Bigler C, Henbühl UK, et al. Human impacts and eutrophication patterns during the past ~200 years at Lago Grande di Avigliana(N. Italy)[J]. Journal of Paleolimnology, 2006, 36:55-67 |

| [45] | Feeser I, Michael O’Connell. Late Holocene land-use and vegetation dynamics in an upland karst region based on pollen and coprophilous fungal spore analyses: an example from the Burren, western Ireland[J]. Vegetation History and Archaeobotany, 2010, 19(5-6):409-426 |

| [46] | 袁靖. 中国古代家养动物的动物考古学研究[J]. 第四纪研究, 2010, 30(2):298-298 |

| [47] | Cai DW, Zhang NF, Zhu SQ, et al. Ancient DNA reveals evidence of abundant aurochs(Bos primigenius) in Neolithic Northeast China[J]. Journal of Archaeological Science, 2018, 98:72-80 |

/

| 〈 |

|

〉 |