The scope of movement of modern humans during the Late Pleistocene in Northeast Asia

Received date: 2018-06-20

Revised date: 2018-12-12

Online published: 2021-02-25

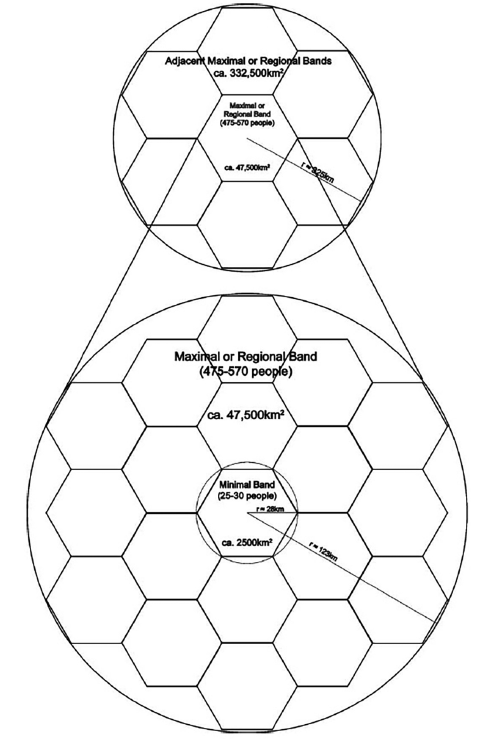

Due to the development of technology and the increase in the number of specialized researchers, a considerable amount of Late Pleistocene sites have been found in Northeast Asia. Issues concerning modern human fossils, Pleistocene environment, lithic manufacturing techniques and human adaptation have been debated based on these archaeological sites. In particular, the provenance analysis of special raw materials as obsidian enables the researches on the movement and the scope of activities of modern humans during the late Pleistocene who had to continuously be on the move for survival. Most researchers have estimated the mobility of hunter-gatherers based on ethnographic researches. The direct and indirect scope of migration of the modern humans can be assumed through the range of Tanged Points and obsidian artifacts of Mt. Baekdu(Changbai). Unlike other lithic manufacturing techniques, the obsidian artifacts were not passed on to several generations but usually used and discarded by a single generation. Benefited from obsidian’s unique chemical composition, it could been seen as the most reliable evidence to indicate the scope of migration.

Lithic manufacturing techniques such as Levallois, Crest, and Yubetsu were widely disseminated over a long time, which is not appropriate to use these lithic techniques to estimate the scope of movement of modern humans. However, the Tanged Point, which had been popularly utilized in a short chronological period and enjoyed a limited distribution in the Northeast Asian region. Based on the distribution of obsidian artifacts from Mt. Baekdu (Changbai) and the Tanged Points, the scope of activity of the modern humans during the Late Pleistocene (MIS 2) is estimated as 193,000~520,000 km2.

Key words: Late Pleistocene; Movement of modern humans; Obsidian; Artifacts; Tanged Points

Cheolmin CHOI , Xing GAO , Wenting XIA , Wei ZHONG . The scope of movement of modern humans during the Late Pleistocene in Northeast Asia[J]. Acta Anthropologica Sinica, 2021 , 40(01) : 12 -27 . DOI: 10.16359/j.cnki.cn11-1963/q.2019.0055

| [1] | Bar-Yosef Mayer DE, Vandermeersch B, Bar-Yosef O. Shells and ochre in Middle Paleolithic Qafzeh Cave, Israel: indications for modern behavior[J]. Journal of Human Evolution, 2009, 56:307-314 |

| [2] | 吕红亮. 更新世晚期到全新世中期青藏高原的狩猎采集者——考古发现与西藏文明史[M]. 北京: 科学出版社, 2015: 45-88 |

| [3] | Bettinger RL. Hunter-Gatherers: Archaeological and Evolutionary Theory[M]. New York: Plenum Press, 1991 |

| [4] | Grove M. Hunter-Gatherer Movement Patterns: Causes and Constraints[J], Journal of Anthropological Archaeology, 2009, 28:222-233 |

| [5] | Kelly RL. The Foraging Spectrum: Diversity in Hunter-Gatherer Lifeways[M]. Washington, DC: Smithsonian, 1995 |

| [6] | Kelly RL. The Lifeways of Hunter-gatherers[M]. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2013 |

| [7] | Binford LR. Willow smoke and dogs’ tails: Hunter-gatherer settlement and archaeological site formation[J]. American Antiquity, 1980, 45:4-20 |

| [8] | Seong CT. Hunter-Gatherer Mobility and Postglacial Cultural Change in the Southern Korean Peninsula[J]. Hanguk Gogo Hakbo, 2009, 72:4-35 |

| [9] | Bird DW, O’Connell JF. Behavioral ecology and archaeology[J]. Journal of Archaeological Research, 2006, 14:143-188 |

| [10] | Merrick HV, Brown FH. Obsidian sources and patterns of source utilization in Kenya and northern Tanzania: Some initial findings[J]. African Archaeological Review, 1984, 2:129-152 |

| [11] | Gamble C. Origins and Revolutions: Human Identity in Earliest Prehistory[M]. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2007 |

| [12] | Le Bourdonnec F, Nomade S, Poupeau G, et al. Multiple origins of Bondi Cave and Ortvale Klde (NW Georgia) obsidians and human mobility in Transcaucasia during[J]. Journal of Archaeological Science, 2012, 39:1317-1339 |

| [13] | Newlander K. Exchange, Embedded Procurement, and Hunter-Gatherer Mobility: A Case Study from the North American Great Basin[D]. Ann Arbor: The University of Michigan, 2012 |

| [14] | Barberena R, Hajduk A, Gil A, et al. Obsidian in the south-central Andes: geological, geochemical, and archaeological assessment of north Patagonian sources (Argentina)[J]. Quaternary International 2011, 245(1): 25-36. |

| [15] | Yakushige M, Sato H. Shirataki obsidian exploitation and circulation in prehistoric northern Japan[J]. Journal of Lithic Studies, 2014, 1:319-342 |

| [16] | Glascock MD, Kuzmin YV, Grebennikov AV, et al. Obsidian provenance for prehistoric complexes in the Amur River basin (Russian Far East)[J]. Journal of Archaeological Science, 2011, 38:1832-1841 |

| [17] | Jia PW, Doelman T, Chen CJ, et al. Moving sources: A preliminary study of volcanic glass artifact distributions in northeast China using PXRF[J]. Journal of Archaeological Science, 2010, 37:1670-1677 |

| [18] | 侯哲. 旧石器时代晚期黑曜岩石器研究——以中国东北地区与南韩地区比较为中心[D]. 首尔:庆熙大学, 2015 |

| [19] | Renfrew C, Dixon JE, Cann JR. Further analysis of Near Eastern Obsidian[J]. Proceedings of the Prehistoric Society, 1968, 34(9): 319-331 |

| [20] | O’Brien MJ, Lyman RL. Applying Evolutionary Archaeology: A Systematic Approach[M]. New York: Kluwer, 2000 |

| [21] | Binford LR. Archaeological perspectives. In New perspectives in Archaeology[M]. New York: A1dine, 1968 |

| [22] | Trigger BG. A History of Archaeological Thought 2nd[M]. Cambridge: Cambride University Press, 2006 |

| [23] | Steward JH. Diffusion and independent invention: a critique of logic[J]. American Anthropologist, 1929, 31:491-495 |

| [24] | Kroeber AL. Historical reconstruction of culture growths and organic evolution[J]. American Anthropologist, 1931, 33:149-156 |

| [25] | Clark G. World Prehistory: A new outline 2nd[M]. Cambridge: Cambride University Press, 1969 |

| [26] | Foley RA, Lahr M. Mode 3 technologies and the evolution of modern humans[J]. Cambridge Archaeological Journal, 1997, 7:3-36 |

| [27] | Bar-Yosef O, Kuhn SL. The big deal about blades: Laminar technologies and human evolution[J]. American Anthropologist, 1999, 101:322-338 |

| [28] | Klein RG. The human career: Human biological and cultural origins 3rd[M]. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2009 |

| [29] | Derevianko AP. Blade and microblade industries in northern, eastern, and central asia. Scenario 1: African orijin and spread to the near east[J]. Archaeology, Ethnology and Anthropology of Eurasia, 2015, 43(2): 3-22 |

| [30] | 木村英明. 総論-旧石器時代の日本列島とサハリン·沿海州[J]. 考古学ジャーナル, 2006, 40:3-6 |

| [31] | 刘玉英, 张淑芹, 刘嘉麒, 等. 东北二龙湾玛珥湖晚更新世晚期植被与环境变化的孢粉记录[J]. 微体古生物学报, 2008, 25(3): 274-280 |

| [32] | 文物保护科学技术研究所14C实验室. 14C年代测定报告(WB) I[A].见:第四纪冰川与第四纪地质论文集第四集:碳十四专集[M]. 北京: 地质出版社, 1987, 13-15 |

| [33] | Akihiro Y, kudo Y, Shimada K, et al. Impact of landscape changes on obsidian exploitation since the Plaeolithic in the central highland of Japan[J]. Veget Hist Archaeobot, 2016, 25:45-55 |

| [34] | Bar-Yosef O. The dispersal of modern humans in Eurasia: a cultural interpretation, In Rethinking Human Revolution[M] Cambridge: McDonald Institute for Archaeological Research, 2007 |

| [35] | Diamond J. Guns, Germs, and Steel: The Fates of Human Societies[M]. New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 1999 |

| [36] | Hassan FA. Population dynamics, in Companion Encyclopedia of Archaeology[M]. London: Routledge, 1999 |

| [37] | Whallon R. Social networks and information: Non-“utilitarian” mobility among hunter-gatherers[J]. Journal of Anthropological Archaeology, 2006, 25:259-270 |

| [38] | Gamble C. The Palaeolithic societies of Europe[M]. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1999 |

| [39] | Phillips SC, Speakman RJ. Initial source evaluation of archaeological obsidian from the Kuril Islands of the Russian Far East using portable XRF[J]. Journal of Archaeological Science, 2009, 36:1256-1263 |

| [40] | Kuzmin YV, Popov VK, Glascock MD, et al. Sources of archaeological volcanic glass in the Primorye (Maritime) province, Russian Far East[J]. Archaeometry, 2002, 44:505-515 |

| [41] | Kim DK, Youn M, Yun CC, et al. PIXE Provenancing of Obsidian Artefacts from Paleolithic Sites in Korea[J]. Bulletin of the Indo-Pacific Prehistory Association, 2007, 27:122-128 |

| [42] | Lee GK, Kim JC. Obsidians from the Sinbuk archaeological site in Korea-Evidences for strait crossing and long distance exchange of raw material in Paleolithic Age[J]. Journal of Archaeological science: Reports 2015, 2:458-466 |

| [43] | Chang YJ. Human activity and lithic technology between Korea and Japan from MIS 3 to MIS 2 in the Late Paleolithic period[J]. Quaternary International, 2013, 308-309: 13e26 |

| [44] | Gyeore Institute Of Cultural Heritage, II Youngsujaeyul, Jung-ri Site, Phocheon[R], Gyeore Institute Of Cultural Heritage, 2016: 1-980 |

| [45] | Yi SB, Jwa YJ. On Provenance of the Prehistoric Obsidian Artifacts in Korea[J]. Hanguk Guseokgi Hakbo, 2015, 31:156-180 |

| [46] | Popov VK, Sakhno VG, Kuzmin YV, et al. Geochemistry of volcanic glasses from the Paektusan volcano[J]. Doklady Earth Science, 2005, 403:803-807 |

| [47] | 陈全家, 田禾, 陈晓颖, 等. 海林炮台山旧石器遗址发现的石器研究[J]. 边疆考古研究, 2010, 9:9-24 |

| [48] | 陈全家, 田禾, 陈晓颖, 等. 秦家东山旧石器地点发现的石器研究[J]. 北方文物, 2014, 2:3-11 |

| [49] | 藁科哲男, 東村武信. 石器の原材産地分析.日本文化財科学会第15回大会研究発表要旨集[M]. 日本文化財科学会, 1998 |

| [50] | Hong MY, Kononenko N. Obsidian use at Hopyeong-dong site, Namyangju[J]. Journal of the Korean Palaeolithic Society, 2005, 12:91-105 |

| [51] | Gangwon Institute for archaeology. Jangheung-ri Paleolithic site[R]. Gangwon Institute for archaeology, 2001: 1-243 |

| [52] | Gangwon Institute for archaeology. Hahwagye-ri III Paleolithic, Mesolithic Site, Hongcheon(III)[R]. Gangwon Institute for archaeology, 2004: 1-264 |

| [53] | Sohn PK. HPaleoenvironment of Middle and Upper Pleistocene KoreaH[A]. In: Paleoenvironment of East Asia from the Mid-Tertiary[C]. Hong Kong, 1983 |

| [54] | Giho Culture Heritage Research Center. Report on the Excavation of Jung-ri Neulgeori Site in Phocheon[R]. Giho Culture Heritage Research Center, 2016: 1-576 |

| [55] | 宁夏文物考古研究所. 水洞沟——1980年发掘报告[R]. 北京: 科学出版社, 2003, 212-215 |

| [56] | 于汇历, 邹向前. 黑龙江省龙江县缸窑地点的细石器遗存[J]. 北方文物, 1992, 8:15 |

| [57] | 崔哲慜, 侯哲, 高星. 朝鲜半岛旧石器时代晚期有柄尖刃器相关研究[J]. 人类学学报, 2017, 36(4): 465-477 |

| [58] | 萟原博文. ナイフ形石器文化後半期の集団領域[J]. 考古研究, 2004, 51(2): 35-54 |

| [59] | Lee HJ. A study of cultural character and changing process of the end of late paleolithic in northeast asia[J]. Journal of the Korean Palaeolithic Society, 1998, 39:58-88 |

| [60] | 李鲜馥, 李婷银, Basra. 蒙古Rashaan Khad遗址调查发掘成果[A]. 见:朝鲜半岛中部内陆的旧石器模样——第11回韩国旧石器学会定期学术大会[C].韩国旧石器学会, 2011 |

| [61] | 张森水. 周口店地区旧石器遗址的发现与研究,中国考古学研究的世纪回顾——旧石器时代考古卷[M]. 北京: 科学出版社, 2004, 29-71 |

| [62] | 安蒜政雄. 剝片尖頭器,湧別技法,黑曜石: 日本海を巡る旧石器時代回廊[J]. 考古學ジャ一ナル 2005, 527 |

| [63] | 陈全家, 赵海龙, 方启, 等. 延边和龙石人沟旧石器遗址2005年试掘报告[J]. 人类学学报, 2010, 29(2): 105-114 |

| [64] | Kuhn SL. Upper Paleolithic raw material economies at ü?ag?izli cave, Turkey[J]. Journal of Anthropological Archaeology. 2004, 23:431-448 |

| [65] | 董祝安. 大布苏的细石器[J]. 人类学学报, 1989, 8(1): 49-59 |

| [66] | 付永平, 陈全家, 袁文明. 沈阳柏家沟西山旧石器地点石器研究[J]. 文物春秋, 2015(1): 3-29 |

/

| 〈 |

|

〉 |