Evolution of cave system at Hualongdong, Anhui and its relation to human occupation

Received date: 2022-03-04

Revised date: 2022-04-29

Online published: 2022-08-10

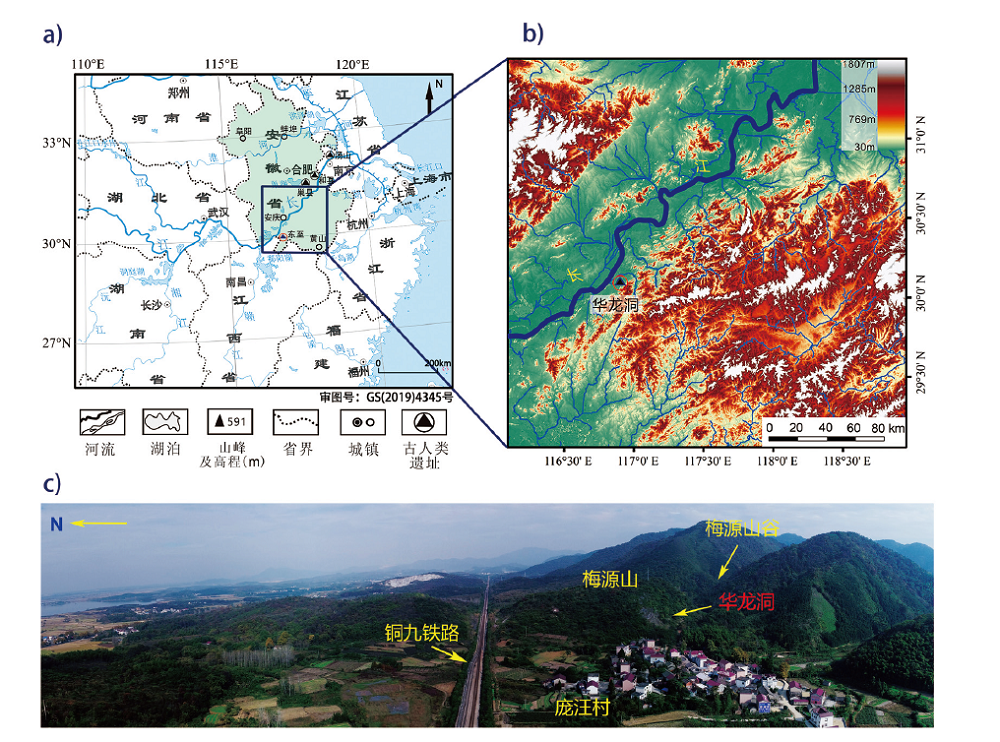

The Hualongdong (HLD) site (latitude 30°06′34.1"N, longitude 116°56′54.2"E, 40 m above sea level) is located in Dongzhi County, Anhui Province, China. It was discovered in 2005. The initial excavations at the HLD site in 2006 yielded a hominin frontal fragment and a lower second molar. Renewed excavations were carried out from 2014 to 2019 field seasons which resulted in the discovery of more than 30 human fossils, an abundance of lithic artifacts and fossil mammal fauna. Biostratigraphic study of faunal remains, as well as Uranium-Thorium dating of speleothems and animal teeth from the brecciated deposits indicated that early human occupied the site most probably took place in the late Middle Pleistocene, ca. 300 ka (270-330 ka). This paper presents the cave development and evolutionary history of the HLD site, and provides explanations of the hominin adapted behavior and the function of the site.

HLD cave is situated in the south slope of a small anticline named Meiyuan Hill. Constrained by the regional geological background, geomorphic features around HLD include lower mountains in the southeast, gentle hills and a lake plain in the northwest. The ancient HLD cave developed in the Upper Cambrian Formation, which consists of banded micritic limestone and dolomitic limestone, materials formed in a deep marine environment, and has been moderately karstified and mineralized over time. The initial formation of the ancient HLD cave likely commenced not later than the early Middle Pleistocene, as many broken speleothems were dated beyond the upper limits of the U-series dating. The original cave deposits were about 20 m higher above its current location, as indicated by the in situ flowstone and stalagmites exposed, which were formed inside the ancient HLD cave. Synsedimentary dismantlement, downward slippage, and bedrock weathering are indicated by the brecciated arrangement of the limestone rock blocks, cemented angular, subangular clasts and archaeological remains within the excavation area. Slipping and collapsing of the cave system proceeded from north to south, probably driven by the down-cutting of the valley and karst erosion.

Bone fragmentation is common and includes both diagenetic and green fractures probably produced by carnivore bone cracking and hominin hammerstone breaking. Additionally, carnivore (tooth pits, gnawing and scores marks) and human (cut marks) actions are documented over the bones. The stone tool assemblage is typical of Mode 1, i.e. the core-and-flake industries. Typologically, the HLD lithic assemblage is small (n=38) and is dominated by quartz (65.8%) and chert (21.1%), plus some lava (10.5%) and limestone (2.6%) artifacts. Most stone tools are complete flakes (60.5%) or debitage (31.6%), with only one specimen each of core, retouched and battered artifact categories. Quartz and lava show fluvial cortex and suggest sourcing from streams, whereas chert nodules derive from the nearby Sinian siliceous carbonate-clastic strata formation. A minimum of 44.4% of the quartz products were obtained through bipolar flaking, whereas all of the chert flakes were knapped with a freehand technique. The raw material quality of chert flakes is high, which may explain heavier reduction observed in their dorsal faces. Most chert flakes show use-wear, probably associated with carcass processing given the presence of cutmarks on some bones.

Although human presence at HLD site is attested by the recovery of their fossils and the small samples of cut-marked bones and stone tools, human activity seems to have been marginal at the site. Two possible scenarios can be deduced, either humans occasionally visited HLD site to briefly process animal remains attracted by carcasses abandoned by carnivores, or natural transport processes such as slope wash or gravity resulted in a fortuitous association between the carnivore-accumulated bone assemblage and lithics.

Shuwen PEI , Yanjun CAI , Zhe DONG , Haowen TONG , Jinchao SHENG , Zetian JIN , Xiujie WU , Wu LIU . Evolution of cave system at Hualongdong, Anhui and its relation to human occupation[J]. Acta Anthropologica Sinica, 2022 , 41(04) : 593 -607 . DOI: 10.16359/j.1000-3193/AAS.2022.0022

| [1] | O'Connor S, Barham A, Aplin K, et al. Cave stratigraphies and cave breccias: Implications for sediment accumulation and removal models and interpreting the record of human occupation[J]. Journal of Archaeological Science, 2017, 77: 143-159 |

| [2] | Goldberge P, Sherwood SC. Deciphering human prehistory through the geoarchaeological study of cave sediments[J]. Evolutionary Anthropology, 2006, 15: 20-36 |

| [3] | 中国科学院地质研究所岩溶研究组. 中国岩溶研究[M]. 北京: 科学出版社, 1979: 1-6 |

| [4] | 北京地方志编辑委员会. 北京志·世界文化遗产卷·周口店遗址志[M]. 北京: 北京出版社, 2004: 1-486 |

| [5] | Liu W, Martinón-Torres M, Cai YJ, et al. The earliest unequivocally modern humans in southern China[J]. Nature, 2015, 526: 696-699 |

| [6] | 宫希成, 郑龙亭, 邢松, 等. 安徽东至华龙洞出土的人类化石[J]. 人类学学报, 2014, 33(4): 427-436 |

| [7] | 陈胜前, 罗虎. 安徽东至县华龙洞旧石器时代遗址发掘简报[J]. 考古, 2013, (4): 7-13 |

| [8] | Wu XJ, Pei SW, Cai YJ, et al. Archaic human remains from Hualongdong, China, and Middle Pleistocene human continuity and variation[J]. PNAS, 2019, 116: 9820-9824 |

| [9] | Wu XJ, Pei SW, Cai YJ, et al. Morphological description and evolutionary significance of 300 ka hominin facial bones from Hualongdong, China[J]. Journal of Human Evolution, 2021, 161: 103052 |

| [10] | 潘桂棠, 肖庆辉. 中国大地构造图(1:2500000)说明书[R]. 北京: 地质出版社, 2015: 1-160 |

| [11] | 安徽省地质矿产局. 安徽省岩石地层[M]. 全国地层多重划分对比研究(34), 武汉: 中国地质大学出版社, 1997 |

| [12] | 都洵, 张永康. 东南区区域地层[M]. 全国地层多重划分对比研究(30), 武汉: 中国地质大学出版社, 1998 |

| [13] | 安徽省地质矿产局区域地质调查队. 中华人民共和国区域地质调查报告:1:5万香隅坂幅(H-50-66-D)、张溪镇幅(H-50-67-A)、东至县幅(H-50-66-C)(地质部分)[R]. 合肥:安徽省地质矿产局, 1991, 1-139 |

| [14] | 李潇丽, 董哲, 裴树文, 等. 安徽东至华龙洞洞穴发育与古人类生存环境[J]. 海洋地质与第四纪地质, 2017, 37(3): 169-179 |

| [15] | 中国科学院地质研究所岩溶研究组. 中国岩溶研究[M]. 北京: 科学出版社, 1979, 148-278 |

| [16] | 同号文, 吴秀杰, 董哲, 等. 安徽东至华龙洞古人类遗址哺乳动物化石的初步研究[J]. 人类学学报, 2018, 37(2): 284-305 |

| [17] | 董哲, 裴树文, 盛锦朝, 等. 安徽东至华龙洞古人类遗址2014-2016年出土的石制品[J]. 第四纪研究, 2017, 37(4): 778-788 |

| [18] | Gao X, Norton CJ. A critique of the Chinese “Middle Palaeolithic”[J]. Antiquity, 2002, 76(292): 397-412 |

| [19] | Pei SW, Xie F, Deng CL. et al. Early Pleistocene archaeological occurrences at the Feiliang site, and the archaeology of human origins in the Nihewan Basin, North China[J]. PLoS One, 2017, 12 (11): e0187251 |

| [20] | Schick KD, Dong ZA. Early Palaeolithic of China and Eastern Asia[J]. Evolutional Anthropology, 1993, 2(1): 22-35 |

| [21] | Binford LR, Ho CK. Taphonomy at a distance: Zhoukoudian, "The Cave Home of Beijing Man"[J]. Current Anthropology, 1985, 26: 413-442 |

| [22] | Boaz NT, Ciochon R, Xu Q. et al. Mapping and taphonomic analysis of the Homo erectus loci at Locality 1 Zhoukoudian, China[J]. Journal of Human Evolution, 2004, 46: 519-549 |

| [23] | Vals A, Dirks PHGM, Backwell LR, d’Errico F. et al. Taphonomic analysis of the faunal assemblage associated with the hominins (Australopithecus sediba) from the Early Pleistocene cave deposits of Malapa, South Africa[J]. PLoS One, 2015, 10: e0126904 |

| [24] | Mangano G. An exclusively hyena-collected bone assemblage in the Late Pleistocene of Sicily: taphonomy and stratigraphic context of the large mammal remains from San Teodoro Cave (North-Eastern Sicily, Italy)[J]. Journal of Archaeological Science, 2011, 38: 3584-3595 |

| [25] | Brain CK. The Hunters or the Hunted? An Introduction to African Cave Taphonomy[M]. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 1981 |

| [26] | Marean CW, Ehrhardt CL. Palaeoanthropological and palaeoecological implications of the taphonomy of a sabertooth's den[J]. Journal of Human Evolution, 1995, 29: 515-547 |

| [27] | Brugal JP, Jaubert J. Les gisements paléontologiques pléistocènes à indices de fréquentation humaine: un nouveau type de comportement de prédation?[J]. Paléo, 1991, 3: 15-41 |

| [28] | Villa P, Soressi M. Stone tools in carnivore sites: The case of Bois Roche[J]. Journal of Anthropological Research, 2000, 56: 187-215 |

| [29] | Stewart M, Andrieux E, Clark-Wilson R, et al. Taphonomy of an excavated striped hyena (Hyaena hyaena) den in Arabia: implications for paleoecology and prehistory[J]. Archaeological and Anthropological Sciences, 2021, 13: 179 |

| [30] | Leslie DE. A dtriped Hyena scavenging event: implications for Oldowan hominid behavior[J]. Field Notes: A Journal of Collegiate Anthropology, 2016, 8 (1): 122-138 |

/

| 〈 |

|

〉 |