A study of the bone awl from the Ziyang Man site, Sichuan Province

Received date: 2022-05-09

Revised date: 2022-05-30

Online published: 2023-02-20

Osseous artifacts manufactured with techniques specifically conceived for such materials, such as cutting, scraping, carving, grinding and polishing, is labeled as formal bone tools and commonly associated with modern human behaviour. Bone awls produced with such techniques are among the most significant components of formal bone tool assemblages uncovered from a large number of the important prehistoric sites in the Old World. In Africa, a bone awl with an age of 98.9±4.5 kaBP was discovered from the Blombos M3 phase; and such implements were also unearthed at a number of sites securely dated to between 75-60 kaBP. In Europe, the earliest age (44-40 kaBP cal) of bone awls which were from the Châtelperronian and the Uluzzian sites in France and Italy, is much younger than that in Africa. In China, the early appearance of bone awls is reported at the Longquan Cave in Henan province and the Ma’anshan Cave in Guizhou province, roughly contemporary to that in Europe.

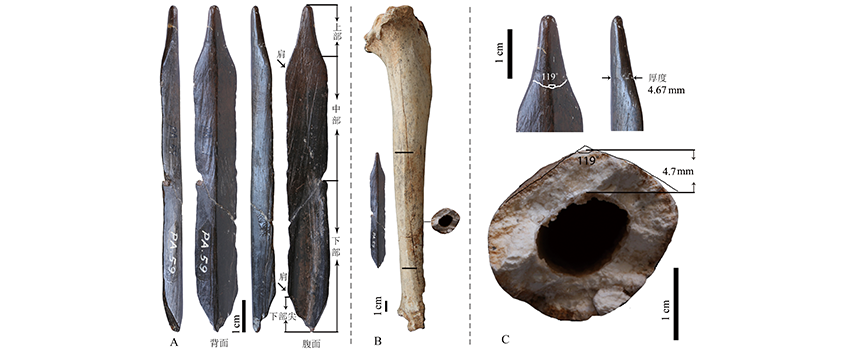

The Ziyang Man site in Sichuan Province is well-known for the discovery of an almost complete skull-cap of late Homo sapiens. However, an entirely modified bone awl, the unique osseous artifact from the site has received little attention after its first appearance in academic works in 1952. In this paper, we present a detailed techno-functional analysis of this bone awl.

By comparing with modern reference collections curated at the IVPP, we conclude this artifact was most probably made from the tibia midshaft of a large-sized deer (most possibly Cervus unicolor), as some anatomical features of this bone element could still be observed on its surface.

Technological and morphometric analyses show the dorsal aspect of this specimen was unevenly scraped, with certain parts of the original compact bone surface still preserved; the ventral aspect, on the contrary, preserved no original bone surface as its distal and medial portion was leveled off by scraping and the proximal portion with a U-shape section was shaped by the repeated gouging with a lithic scraper.

Microscopic observation of the bone awl shows that rounding, fine transverse striations and polish are confined mostly within a limited area of both its tips. This is in full agreement with the features of ethnographic and experimental examples of awls used to piece hide and skins, as well as those of archaeological specimens of well-established functions.

Observation of the specimen under microscope revealed the presence of red residues still adhering to the distal tip of the bone awl. Both the SEM-EDS (Scanning Electron Microscope-Energy Dispersive Spectrometer) and LIBS (Laser-Induced Breakdown Spectroscopy) analyses of the sampled red residues detect Fe-rich components, and yield spectra with peaks centered on Fe element more intense than the control samples lacking red residues. We thus suggest that the distal tip of the awl might have been stained by ochre powder when it was used for hide or skin piercing.

Through comparative studies with the alike finds from the archaeological sites of southern China, the regional specificity as well as human behaviors embodied in this artifact were tentatively explored and it seems reasonable to argue that the bone artifact from the Ziyang Man site was an exemplary osseous tool in prehistoric China with signs of multi-functionality and clearly identified ochre residues on its functional unit.

Key words: Ziyang Man; bone tools; bone awl; ochre; micro-wear

Yue ZHANG , Xiujie WU , Shuangquan ZHANG . A study of the bone awl from the Ziyang Man site, Sichuan Province[J]. Acta Anthropologica Sinica, 2023 , 42(01) : 1 -14 . DOI: 10.16359/j.1000-3193/AAS.2023.0002

| [1] | Gates Saint-Pierre C, Walker RB. Bones as Tools: Current Methods and Interpretations in Worked Bone Studies[J]. British Archaeological Reports International Series. Vol 1622. Oxford: Archaeopress, 2007, 1-182 |

| [2] | Backwell LR, d’Errico F. The first use of bone tools: a reappraisal of the evidence from Olduvai Gorge, Tanzania[J]. Palaeontologia africana, 2004, 40(9): 95-158 |

| [3] | Ma S, Doyon L. Animals for Tools: The Origin and Development of Bone Technologies in China[J]. Frontiers in Earth Science, 2021, 9: 784313 |

| [4] | Klein RG. The Human Career:Human Biological and Cultural Origins (3rd Edition)[M]. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2009 |

| [5] | Mellars P. Renfrew C (ed). The character of the Middle-Upper Palaeolithic transition in south-west FranceIn: Renfrew C (ed). The Explanation of Culture Change:Models in Prehistory[C]. London: Duckworth, 1973, 255-276 |

| [6] | McBrearty S, Brooks AS. The revolution that wasn’t: a new interpretation of the origin of modern human behavior[J]. Journal Of Human Evolution, 2000, 39(5): 453-563 |

| [7] | Henshilwood CS, d’Errico F, Marean CW, et al. An early bone tool industry from the Middle Stone Age at Blombos Cave, South Africa: implications for the origins of modern human behaviour, symbolism and language[J]. Journal Of Human Evolution, 2001, 41 (6): 631-678 |

| [8] | d’Errico F, Henshilwood C, Lawson G, et al. Archaeological evidence for the emergence of language, symbolism, and music-an alternative multidisciplinary perspective[J]. Journal of World Prehistory, 2003, 17(1): 1-70 |

| [9] | 安家瑗. 华北地区旧石器时代的骨、角器[J]. 人类学学报, 2001, 20: 319-330 |

| [10] | Breitborde R. A functional bone tool analysis[D]. M.A Thesis. Northridge: california state university northridge, 1983 |

| [11] | Keddie G. Bone Awls: Bridging or Widening the Gaps between Archaeology and Ethnology[J]. The Midden, 2016, 44 (1): 10-12 |

| [12] | Owen L. distoring the past[M]. Tübingen: Kerns Verlag, 2005 |

| [13] | Wilbur CK. The New England Indians[M]. Chester, Connecticut: Globe Pequot Press, 1978 |

| [14] | Miles C. Indian and Eskimo Artifacts of North America[M]. New York: American Legacy Press, 1963 |

| [15] | Birket-Smith K. Ethnological collections from the northwest passage[J]. Report of the Fifth Thule Expedition, 1921-24. Vol 6. Copenhagen: Nordisk Forlag; 1945 |

| [16] | d’Errico F, Julien M, Liolios D, et al. Many awls in our argument. Bone tool manufacture and use in the Chatelperronian and Aurignacian levels of the Grotte du Renne at Arcy-sur-Cure[A]. In: Zilhao J, d’Errico F (eds). The Chronology of the Aurignacian and of the Transitional Technocomplexes: Dating, Stratigraphies, Cultural Implications: Proceedings of Symposium 6.1 of the XIVth Congress of the UISPP[C]. Lisbon: Instituto Portugués de Arqueología, 2003, 247-270 |

| [17] | d’Errico F, Backwell LR, Wadley L. Identifying regional variability in Middle Stone Age bone technology: The case of Sibudu Cave[J]. Journal of Archaeological Science, 2012, 39 (7):2479-2495 |

| [18] | Zhang S, Doyon L, Zhang Y, et al. Innovation in bone technology and artefact types in the late Upper Palaeolithic of China: Insights from Shuidonggou Locality 12[J]. Journal of Archaeological Science, 2018, 93 (3): 82-93 |

| [19] | 刘旻, 王运辅, 付永旭, 等. 简论贵州高原史前时代的骨角铲、锥系统[J]. 南方文物, 2019, 5: 210-219 |

| [20] | Jacobs Z, Duller GA, Wintle AG, et al. Extending the chronology of deposits at Blombos Cave, South Africa, back to 140ka using optical dating of single and multiple grains of quartz[J]. Journal Of Human Evolution, 2006, 51(3): 255-273 |

| [21] | d’Errico F, Henshilwood CS. Additional evidence for bone technology in the southern African middle stone age[J]. Journal Of Human Evolution, 2007, 52(2): 142-163 |

| [22] | Backwell L, d’Errico F, Wadley L. Middle Stone Age bone tools from the Howiesons Poort Layers, Sibudu Cave, South Africa[J]. Journal of Archaeological Science, 2008, 35(6): 1566-1580 |

| [23] | d’Errico F, Borgia V, Ronchitelli A. Uluzzian bone technology and its implications for the origin of behavioural modernity[J]. Quaternary International, 2012, 259: 59-71 |

| [24] | d’Errico F. The invisible frontier. A multiple species model for the origin of behavioral modernity[J]. Evolutionary Anthropology, 2003, 12(4): 188-202 |

| [25] | 北京师范大学历史学院, 洛阳市文物考古研究院, 栾川县文物管理所. 河南栾川龙泉洞遗址2011年发掘报告[J]. 考古学报, 2017, 2: 227-248 |

| [26] | Du S, Li X, Zhou L, et al. Longquan Cave: an early Upper Palaeolithic site in Henan Province, China[J]. Antiquity, 2016, 90(352): 876-893 |

| [27] | Zhang S, d’Errico F, Backwell LR, et al. Ma’anshan cave and the origin of bone tool technology in China[J]. Journal of Archaeological Science, 2016, 65: 57-69 |

| [28] | 裴文中, 吴汝康, 资阳人. 中国科学院古脊椎动物与古人类研究所甲种专刊(第1号)[J]. 北京:科学出版社, 1957, 1-71 |

| [29] | 成都地质学院第四纪科研组. 资阳人化石地层时代问题的商榷[J]. 考古学报, 1974, 2: 111-124 |

| [30] | 安志敏. 关于我国若干原始文化年代的讨论[J]. 考古, 1972, 42(1): 57-89 |

| [31] | 李宣民, 张森水. 资阳人B地点发现的旧石器[J]. 人类学学报, 1984, 3(3): 215-224 |

| [32] | 吴汝康, 吴新智. 中国古人类遗址[M]. 上海: 上海科技教育出版社, 1999 |

| [33] | 吴秀杰, 严毅. 资阳人头骨化石的内部解剖结构[J]. 人类学学报, 2020, 39(4): 511-520 |

| [34] | 中国科学院考古研究所实验室. 放射性碳素测定年代报告(一)[J]. 考古, 1972, 11: 52-56 |

| [35] | d’Errico F, Doyon L, Zhang S, et al. The origin and evolution of sewing technologies in Eurasia and North America[J]. Journal Of Human Evolution, 2018, 125: 71-86 |

| [36] | Zhang Y, Gao X, Pei SW, et al. The bone needles from Shuidonggou locality 12 and implications for human subsistence behaviors in North China[J]. Quaternary International, 2016, 400: 149-157 |

| [37] | Zhang Y, Doyon L, Peng F, et al. An Upper Paleolithic Perforated Red Deer Canine With Geometric Engravings From QG10, Ningxia, Northwest China[J]. Frontiers in Earth Science, 2022, 10: 814761 |

| [38] | Lyman RL. Vertebrate Taphonomy[M]. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1994, 1-552 |

| [39] | Dominguez-Rodrigo M, de Juana S, Galan AB, et al. A new protocol to differentiate trampling marks from butchery cut marks[J]. Journal of Archaeological Science, 2009, 36(12): 2643-2654 |

| [40] | Buc N. Experimental series and use-wear in bone tools[J]. Journal of Archaeological Science, 2011, 38(3):546-557 |

| [41] | Griffitts JL. Bone tools and technological choice: change and stability on the Northern Plains[D]. Ph.D Dissertation. Arizona: University of Arizona, 2006 |

| [42] | Legrand A, Radi G. Manufacture and use of bone points from Early Neolithic Colle Santo Stefano, Abruzzo, Italy[J]. Journal Of Field Archaeology, 2008, 33(3): 305-320 |

| [43] | Legrand A, Sidéra I. Gates St-Pierre C, Walker R eds. Methods, means and results when studying European bone industries[A]. In: Gates St-Pierre C, Walker R(eds). Bones as Tools: Current Methods and Interpretations in Worked Bone Studies[C]. British Archaeological Reports International Series 1622. Oxford:Archaeopress, 2007, 291-304 |

| [44] | LeMoine GM. Use wear on bone and antler tools from the Mackenzie Delta, Northwest Territories[J]. American Antiquity, 1994, 59 (2): 316-334 |

| [45] | Buc N, Loponte D. Bone Tool Types and Microwear Patterns: Some Examples from the Pampa Region, South America[J]. In: Gates St-Pierre C, Walker R(eds). Bones as Tools: Current Methods and Interpretations in Worked Bone Studies[C]. Oxford: British Archaeological Reports International Series 1622. Archaeopress, 2007, 143-157 |

| [46] | Pasveer J. Bone Artefacts from Liang Lemdubuand Liang Nabulei Lisa, Aru Islands[J]. Terra Australis, 2007, 22: 235-254 |

| [47] | Pasveer JM. The Djief Hunters, 26,000 Years of Rainforest Exploitation on the Bird’s Head of Papua, Indonesia[J]. Modern Quaternary Research in Southeast Asia. Vol 17. Lisse: A. A. Balkema, 2004 |

| [48] | Sillitoe P. Made in Niugini: technology in the Highlands of Papua New Guinea[M]. London: British Museum Publications, 1988 |

| [49] | St-Pierre CG. Bone awls of the St. Lawrence Iroquoians: a microwear analysis[A]. In: Gates St-Pierre C, Walker R(eds). Bones as Tools: Current Methods and Interpretations in Worked Bone Studies, BAR International Series[C]. Oxford: Archaeopress, 2007, 107-118 |

| [50] | Bradfield J. Use-trace analysis of bone tools: a brief overview of four methodological approaches[J]. The South African Archaeological Bulletin, 2015, 70(201): 3-14 |

| [51] | Williamson B. Subsistence Strategies in the Middle Stone Age at Sibudu Cave: The Microscopic Evidence from Stone Tool Residues[A]. In: d’Errico F, Backwell L(eds). From Tools to Symbols: From Early Hominids to Modern Humans[C]. Johannesburg: Witwatersrand University Press, 2005, 493-511 |

| [52] | Rifkin RF. Assessing the Efficacy of Red Ochre as a Prehistoric Hide Tanning Ingredient[J]. Journal of African Archaeology, 2011, 9(2): 131-158 |

| [53] | Henshilwood CS, Sealy JC, Yates R, et al. Blombos Cave, Southern Cape, South Africa: Preliminary Report on the 1992-1999 Excavations of the Middle Stone Age Levels[J]. Journal of Archaeological Science, 2001, 28(4): 421-448 |

| [54] | d’Errico F, Backwell L, Villa P, et al. Early evidence of San material culture represented by organic artifacts from Border Cave, South Africa[J]. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 2012, 109(33): 13214-13219 |

| [55] | Wang FG, Yang SX, Ge JY, et al. Innovative ochre processing and tool use in China 40,000 years ago[J]. Nature, 2022, 603: 284-289 |

| [56] | d’Errico F. La vie sociale de l’art mobilier Paléolithique. Manipulation, transport, suspension des objets on os, bois de cervidés, ivoire[J]. Oxford Journal of Archaeology, 1993, 12(2): 145-174 |

| [57] | Qu TL, Bar-Yosef O, Wang Y, et al. The Chinese Upper Paleolithic: Geography, Chronology and Techno-typology[J]. Journal of Archaeological Research, 2013, 21(1): 1-73 |

| [58] | Pasveer JM, Bellwood P. Prehistoric bone artefacts from the northern Moluccas, Indonesia[A]. In: Keates SG, Pasveer JM (eds). Quaternary Research in Indonesia[C]. Lisse: A.A. Balkema Publishers, 2004, 301-359 |

| [59] | 柳州市博物馆, 广西壮族自治区文物工作队. 柳州市大龙潭鲤鱼嘴新石器时代贝丘遗址[J]. 考古, 1983, 9: 769-774 |

| [60] | 张森水. 穿洞史前遗址(1981年发掘)初步研究[J]. 人类学学报. 1995, 14(2): 132-146 |

| [61] | 毛永琴, 曹泽田. 贵州穿洞遗址1979年发现的磨制骨器的初步研究[J]. 人类学学报, 2012, 31(4): 335-343 |

/

| 〈 |

|

〉 |