Discovery and research of the engraved remains in the early and middle Paleolithic periods

Received date: 2021-11-11

Revised date: 2022-03-07

Online published: 2023-04-03

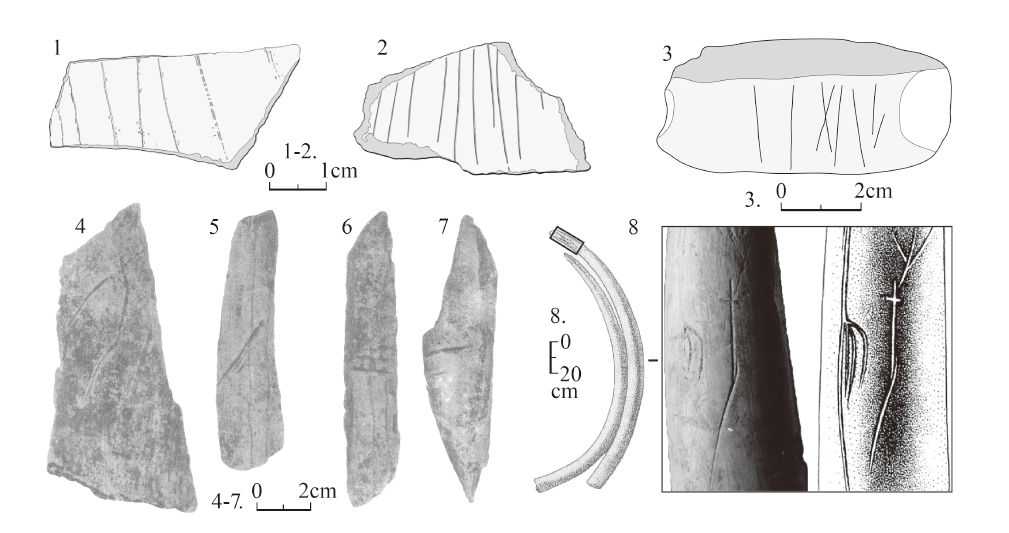

Engravings are important archaeological materials that prehistoric humans deliberately scribed, and play an important role in revealing and exploring the development and evolution of cognitive and thinking expression abilities of ancient humans. At present, the discovery and research of engravings are mainly concentrated in Europe, southern Africa and west Asia, but there are few engravings found in China. This article emphatically introduces the current findings and researches on engravings at home and abroad. On this basis, we summarize the identification and analysis methods of engravings and try to explore the differences of engravings in different time and space. The interference factors for the identification of engravings mainly include two aspects: One is the unconscious or functional modification by prehistoric humans; The other one is the taphonomic influence. Macroscopically, the scratches produced by these interference factors are usually scattered and irregular, and different from the purposeful, conscious and designable engravings. Microscopically, the researchers usually use microscope and build 3D digital models, so that they can more carefully observe the characteristics of the engravings and get more quantitative statistics, which can be used for comparative analysis to identify authenticity more scientifically and rigorously. In the early Paleolithic, there are few engravings, and the carved patterns are simple, but they have obvious artificial design intention. In the middle Paleolithic, the engravings not only increased in distribution area and the number of specimens, but also became more diverse in carrier types and graphical representations. More than 20 middle Paleolithic sites with engravings were found in Europe. The types of carrier include bone, nummulite, chert and bedrock. Engraving patterns are mainly parallel or sub-parallel lines, stacked chevrons with more complex graphic design and technological process also appear. In addition, there are also cross intersection, zigzag and cross-hatched design. Compared to Europe, the sites with engravings in Africa are less, but the specimens in individual site are more. The non-utilitarian ochre and ostrich eggshells become the main carriers, which is obviously different from the situation in Europe. The carved patterns found in Africa are generally more standardized, more designable, and more complex in graphical representation, mainly reflect in fan shaped motif, hatched band motif, curved lines that cross a central line and diamond shaped pattern found in Klipdrift Shelter, Dieploof Rock Shelter and Blombos Cave. And part of these patterns are often found in different layers of the site, there is inheritance and continuation. The engravings of the Middle Paleolithic in Asia are mainly found in Western Asia and Lingjing site in China. Among them, the engravings at Quneitra site in Israel with some disconnected parts forming a unified whole are the most distinctive. The characteristics of the engravings at Mar-Tarik, Qafzeh Cave and Lingjing site are similar to those in Europe, with parallel or sub-parallel lines being the main pattern and with bones being the main carrier. It is worth noting that ochre pigments are found on the engravings of Lingjing site, further increases the symbolic significance of these specimens.

Key words: Paleolithic; Engravings; Geometric figure; Bones; Ochre

Sanling LI . Discovery and research of the engraved remains in the early and middle Paleolithic periods[J]. Acta Anthropologica Sinica, 2023 , 42(02) : 288 -303 . DOI: 10.16359/j.1000-3193/AAS.2022.0046

| [1] | Henshilwood CS, d’Errico F, Yates R, et al. Emergence of modern human behavior: Middle Stone Age engravings from South Africa[J]. Science, 2002, 295(5558): 1278-1280 |

| [2] | Li ZY, Doyon L, Li H, et al. Engraved bones from the archaic hominin site of Lingjing, Henan Province[J]. Antiquity, 2019, 93(370): 886-900 |

| [3] | 彭菲, 高星, 王惠民, 等. 水洞沟旧石器时代晚期遗址发现带有刻划痕迹的石制品[J]. 科学通报, 2012, 57(26): 2475-2481 |

| [4] | Shaham D, Belfer-Cohen A, Rabinovich R, et al. A Mousterian Engraved Bone: Principles of Perception in Middle Paleolithic Art[J]. Current Anthropology, 2019, 60(5): 708-716 |

| [5] | Texier P-J, Porraz G, Parkington J, et al. A Howiesons Poort tradition of engraving ostrich eggshell containers dated to 60,000 years ago at Diepkloof Rock Shelter, South Africa[J]. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 2010, 107: 6180-6185 |

| [6] | Henshilwood CS, d’Errico F, Watts I. Engraved ochres from the Middle Stone Age levels at Blombos Cave, South Africa[J]. Journal of Human Evolution, 2009, 57: 27-47 |

| [7] | Boule M, Breuil H, Licent E, et al. Le Paléolithique de la Chine[M]. Paris: Archives de 1’ Institut de Paléontologie Humaine, 1928, 4: 1-138 |

| [8] | Pei WC. Preliminary Note on Some Incised, Cut and Broken Bones Found in Association with Sinanthropus Remains and Lithic Artifacts from Choukoutien[J]. Bulletin of the Geological Society of China, 1933, 12: 105-112 |

| [9] | 裴文中. 旧石器时代之艺术[M]. 上海: 商务印书馆,1935 |

| [10] | 高星, 黄万波, 徐自强, 等. 三峡兴隆洞出土12-15万年前的古人类化石和象牙刻划[J]. 科学通报, 2003, 48(23): 2466-2472 |

| [11] | Norton CJ, Jin JJH. The evolution of modern human behavior in East Asia: Current perspectives[J]. Evolutionary Anthropology, 2009, 18: 247-260 |

| [12] | Li ZY, Wu XJ, Zhou LP, et al. Late Pleistocene archaic human crania from Xuchang, China[J]. Science, 2017, 355: 969-972 |

| [13] | 尤玉柱. 峙峪遗址刻划符号初探[J]. 科学通报, 1982(16): 1008-1010 |

| [14] | Pei WC. A preliminary report on the Late Palaeolithic cave of Choukoutien[J]. Acta Geologica Sinica, 1934, 13: 327-358 |

| [15] | Li F, Bae CJ, Ramsey CB, et al. Re-dating Zhoukoudian Upper Cave, northern China and its regional significance[J]. Journal of Human Evolution, 2018, 121: 170-177 |

| [16] | Bednarik RG. Palaeolithic art found in China[J]. Nature, 1992, 356: 116 |

| [17] | Bednarik RG. The Pleistocene art of Asia[J]. Journal of World Prehistory, 1994, 8: 351-375 |

| [18] | d’Errico F, Vanhaeren M, Henshilwood CS, et al. From the origin of language to the diversification of languages: What can archaeology and palaeoanthropology say?[A]. In: Becoming Eloquent: Advances in the emergence of language, human cognition, and modern cultures[C]. Amsterdam: John Benjamins Publishing Company, 2009, 13-68 |

| [19] | Mackay A, Welz A. Engraved ochre from a Middle Stone Age context at Klein Kliphuis in the Western Cape of South Africa[J]. Journal of Archaeological Science, 2008, 35(6): 1521-1532 |

| [20] | d’Errico F, GarcíaMoreno R, Rifkin RF. Technological, elemental and colorimetric analysis of an engraved ochre fragment from the Middle Stone Age levels of Klasies River Cave 1, South Africa[J]. Journal of Archaeological Science, 2012, 39: 942-952 |

| [21] | Hodgskiss T. Cognitive requirements for ochre use in the middle stone age at Sibudu, South Africa[J]. Cambridge Archaeological Journal, 2014, 24(3): 405-428 |

| [22] | Watts I. The pigments from Pinnacle Point Cave 13B, Western Cape, South Africa[J]. Journal of Human Evolution, 2010, 59: 392-411 |

| [23] | Henshilwood CS, van Niekerk KL, Wurz S, et al. Klipdrift Shelter, southern Cape, South Africa: preliminary report on the Howiesons Poort layers[J]. Journal of Archaeological Science, 2014, 45: 284-303 |

| [24] | Vogelsang R, Richter J, Jacobs Z, et al. New excavations of Middle Stone Age deposits at Apollo 11 Rockshelter, Namibia: stratigraphy, archaeology, chronology and past environments[J]. Journal of African Archaeology, 2010, 8(2): 185-218 |

| [25] | Texier P-J, Porraz G, Parkington J, et al. The context, form and significance of the MSA engraved ostricheggshell collection from Diepkloof Rock Shelter, Western Cape, South Africa[J]. Journal of Archaeological Science, 2013, 40: 3412-3431 |

| [26] | Henshilwood CS, d’Errico F, Marean CW, et al. An Early Bone Tool Industry from the Middle Stone Age at Blombos Cave, South Africa: Implications for the Origins of Modern Human Behaviour, Symbolism and Language[J]. Journal of human evolution, 2002, 41(6): 631-678 |

| [27] | d’Errico F, Henshilwood CS. Additional evidence for bone technology in the southern African Middle Stone Age[J]. Journal of Human Evolution, 2007, 52: 142-163 |

| [28] | Cain CR. Notched, flaked and ground bone artefacts from Middle Stone Age and Iron Age layers of Sibudu Cave, KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa[J]. South African Journal of Science, 2004, 100: 195-197 |

| [29] | Sirakov N, Guadelli J-L, Ivanova S, et al. An ancient continuous human presence in the Balkans and the beginnings of human settlement in western Eurasia: a Lower Pleistocene example of the Lower Palaeolithic levels in Kozarnika cave (North-western Bulgaria)[J]. Quaternary International, 2010, 223: 94-106 |

| [30] | Mania D, Mania U. The natural and socio-cultural environment of Homo erectus at Bilzingsleben, Germany[A]. In: The hominid individual in context: Archaeological Investigations of Lower and Middle Palaeolithic landscapes, locales and artefacts[C]. United Kingdom: Routledge, 2005, 98-114 |

| [31] | Bednarik RG. The Bilzingsleben engravings in the context of Lower Palaeolithic palaeoart[J]. Erkenntnisj?ger: Kultur und Umwelt des frühen Menschen, Landesamt für Arch?ologie Sachsen-Anhalt, 2003, 43-49 |

| [32] | Rodríguez-Vidal J, d’Errico F, Pacheco FG, et al. A rock engraving made by Neanderthals in Gibraltar[J]. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 2014, 111: 13301-13306 |

| [33] | Majki? A, d’Errico F, Milo?evi? S. Sequential incisions on a cave bear bone from the Middle Paleolithic of Pe?turina Cave, Serbia[J]. Journal of Archaeological Method and Theory, 2018, 25: 69-116 |

| [34] | Bednarik RG. The earliest evidence of palaeoart[J]. Rock Art Research, 2003, 20(2): 89-135 |

| [35] | Bednarik RG. Concept-Mediated Marking in the Lower Palaeolithic[J]. Current Anthropology, 1995, 36(4): 605-634 |

| [36] | Marshack A. Some implications of the Paleolithic symbolic evidence for the origin of language[J]. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 1976, 280: 289-311 |

| [37] | Zilh?o J. The emergence of ornaments and art: an archaeological perspective on the origins of Behavioral modernity[J]. Journal of Archaeological Research, 2007, 15: 1-54 |

| [38] | Frayer DW, Orschiedt J, Cook J, et al. Krapina 3: Cut marks and ritual behavior?[J]. Periodicum Biologorum, 2006, 108(4): 519-524 |

| [39] | Leder D, Hermann R, Hüls M, et al. A 51,000-year-old engraved bone reveals Neanderthals’ capacity for symbolic behaviour. Nature Ecology & Evolution, 2021, 5: 1273-1282 |

| [40] | Crémades M, Laville H, Sirakov N. Une pierregravéede 50 000 ans B.P. dans les Balkans[J]. Paléo, 1995, 7: 201-209 |

| [41] | García-Diez M, Fraile BO, Maestu IB. Neanderthal graphic behavior: the pecked pebble from Axlor rockshelter (northern Spain)[J]. Journal of Anthropological Research, 2013, 69: 397-410 |

| [42] | Majki? A, d’Errico F, Stepanchuk V. Assessing the significance of Palaeolithic engraved cortexes: a case study from the Mousterian site of Kiik-Koba, Crimea[J]. PLoS ONE, 2018, 13: e0195049 |

| [43] | d’Errico F, Julien M, Liolios D, et al. Many awls in our argument: bone tool manufacture and use in the Chatelperronian and Aurignacian levels of the Grotte du Renne at Arcy-sur-Cure[A]. In: The chronology of the Aurignacian and of the transitional technocomplexes: dating, stratigraphies, cultural implications[C]. Lisbon: Instituto Português de Arqueologia, 2003, 247-270 |

| [44] | Vicent A. Remarques préliminaires concernant l’outillage osseux de la Grotte Vaufrey[A]. In: J.P. Rigaud(Ed.), La Grotte Vaufrey. Paléoenvironnement, Chronologie, Activités Humaines[C]. Mémoires de la Société Préhistorique Fran?aise, 1988, 19: 529-533 |

| [45] | Langley MC, Clarkson C, Ulm S. Behavioural complexity in Eurasian Neanderthal populations: a chronological examination of the archaeological evidence[J]. Cambridge Archaeological Journal, 2008, 18: 289-307 |

| [46] | d’Errico F, Doyon L, Colagé I, et al. From number sense to number symbols: an archaeological perspective[J]. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B, 2018, 373(1470): 1-10 |

| [47] | d’Errico F. Palaeolithic origins of artificial memory systems: an evolutionary perspective[A]. In: Cognition and material culture: the archaeology of symbolic storage[C]. Cambridge: McDonald Institute for Archaeological Research, 1998, 19-50 |

| [48] | d’Errico F, Zilh?o J, Julien M, et al. Neanderthal acculturation in Western Europe? A critical review of the evidence and its interpretation[J]. Current Anthropology, 1998, 39: 1-44 |

| [49] | Marshack A. The roots of civilization: the cognitive beginnings of man’s first art, symbol and notation[M]. Mt. Kisco: Moyer Bell Ltd., 1991 |

| [50] | Pradel L, Pradel JH. Le Moustérien évolué de l’Ermitage[J]. L’Anthropologie, 1954, 58: 433-445 |

| [51] | Joordens JCA, d’Errico F, Wesselingh FP, et al. Homo erectus at Trinil on java used shells for tool production and engraving[J]. Nature, 2015, 518: 228-231 |

| [52] | Hovers E, Vandermeersch B, Bar-Yosef O. A Middle Paleolithic engraved artefact from Qafzeh Cave, Israel[J]. Rock Art Research, 1997, 14: 79-87 |

| [53] | Jaubert J, Biglari F, Mourre V, et al. The Middle Palaeolithic occupation of Mar-Tarik, a new Zagros Mousterian site in Bisotun massif (Kermanshah, Iran)[A]. In: Iran Palaeolithic/Le paléolithique d’Iran[C]. Oxford: Archaeopress, 2009, 7-27 |

| [54] | d’Errico F, Henshilwood C, Lawson G, et al. Archaeological evidence for the emergence of language, symbolism, and music: an alternative multidisciplinary perspective[J]. Journal of World Prehistory, 2003, 17(1): 1-70 |

| [55] | L’ Homme V, Normand E. Présentation des galets striés de la couche inférieure du gisement moustérien de ‘Chez Pourré-Chez Comte’ (Corrèze)[J]. Paléo, 1993, 5: 121-125 |

| [56] | Peresani M, Dallatorre S, Astuti P, et al. Symbolic or utilitarian? Juggling interpretations of Neanderthal behavior: new inferences from the study of engraved stone surfaces[J]. Journal of Anthropological Sciences, 2014, 92: 233-255 |

| [57] | Stepanchuk VN. Prolom II, a Middle Palaeolithic Cave Site in the Eastern Crimea with Non-Utilitarian Bone Artefacts[J]. Proceedings of the Prehistoric Society, 1993, 59: 17-37 |

| [58] | Behrensmeyer AK, Gordon KD. & Yanagi GT. Trampling as a cause of bone surface damage and pseudo-cutmarks. Nature, 1986, 319: 768-771 |

/

| 〈 |

|

〉 |