Analysis methods on Paleolithic age archaeological remains of ochre using

Received date: 2023-02-27

Revised date: 2023-05-26

Online published: 2024-04-02

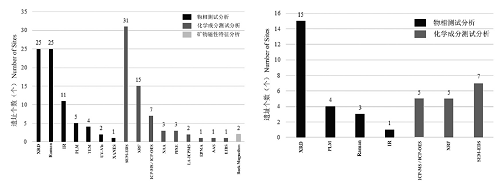

Ochre is one of the most common mineral pigments in archaeological studies. The current archaeological evidence suggests that the use of ochre became more common since 100 ka years ago, which was important for human adaptation to the more drastic environmental changes and the continuous interaction of social culture network. Recently, more and more archaeological remains related to ochre-using have been unearthed and identified in China, however, the research work needs to be further developed. Therefore, how to make comprehensive use of various test schemes to deeply explore the development pattern and ethnological significance of human behavior indicated by the ochre pigment needs us to make a systematic summary. In this paper, referring to the international studies in the fields of archaeology, geophysics and chemistry, ethnology and so on, we concluded the main parts of paleolithic age archaeological ochre analysis asthe qualitative chemical composition, analysis of provenance, and operational technology. The multidisciplinary comprehensive analysis on archaeological remains of ochre using is a potential research field, hitherto, the examples of domestic ochre using is still limited.

Key words: Paleolithic; Ochre; Physicochemical analysis; Anthropology

XU Jingwen , HUAN Faxiang , YANG Shixia . Analysis methods on Paleolithic age archaeological remains of ochre using[J]. Acta Anthropologica Sinica, 2024 , 43(02) : 331 -343 . DOI: 10.16359/j.1000-3193/AAS.2023.0061

| [1] | Foley RA, Martin L, Lahr MM, et al. Major transitions in human evolution[J]. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B, 2016, 371: 20150229 |

| [2] | Cornell RM, Schwertmann U. The iron oxides: structure, properties, reactions, occurrences and uses[M]. Wiley-VCH. 2003 |

| [3] | Nicola M, Mastrippolito C, Masic A. Iron Oxide-Based pigment and their use in history[A]. In Faivre D. Iron oxide: from nature to applications[C]. New Jersey: Wiley Press. 2016: 544-566 |

| [4] | Watts I, Chazan M, Wilkins J. Early evidence for brilliant ritualized display: specularite use in the Northern Cape (South Africa) between similar to 500 and similar to 300 Ka[J]. Current Anthropology, 2016, 57(3): 287-310 |

| [5] | Brooks AS, Yellen JE, Potts Richard, et al. Long-distance stone transport and pigment use in the earliest Middle Stone Age[J]. Science, 2018, 360(6384): 90-94 |

| [6] | 杨石霞, 许竞文, 浣发祥. 古人类对赭石的利用行为在其演化中的意义[J]. 人类学学报, 2022, 41(4): 649-658 |

| [7] | Barham LS. Systematic pigment use in the Middle Pleistocene of South-Central Africa[J]. Current Anthropology, 2002, 43(1): 181-190 |

| [8] | 周玉端, 翟天民, 李桓. 旧石器时代人类对赭石的利用[J]. 江汉考古, 2017(2): 43-51 |

| [9] | 申艳茹. 中国旧石器时代遗址中赭石的功能[J]. 南方文物, 2020(1): 187-192 |

| [10] | D’Errico F, Moreno RC, Rifkin RF. Technological, elemental and colorimetric analysis of an engraved ochre fragment from the Middle Stone Age levels of Klasies River Cave 1, South Africa[J]. Journal of Archaeological Science, 2012, 39(4): 942-952 |

| [11] | Velliky EC, Porr M, Conard NJ. Ochre and pigment use at Hohle Fels cave: results of the first systematic review of ochre and ochre-related artefacts from the Upper Palaeolithic in Germany[J]. PLoS One, 2018, 13(12): e0209874 |

| [12] | D'Errico F, Pitarch Martí A, Wei Y. Zhoukoudian Upper Cave personal ornaments and ochre: rediscovery and reevaluation[J]. Journal of human evolution, 2021, 161: 103088 |

| [13] | Wang FG, Yang SX, Ge JY, et al. Innovative ochre processing and tool use in China 40,000 years ago[J]. Nature, 2022, 603(7900): 284-289 |

| [14] | Marean CW, Bar-Matthews M, Bernatchez J, et al. Early human use of marine resources and pigment in South Africa during the Middle Pleistocene[J]. Nature, 2007, 449(7164): 905-908 |

| [15] | Cuenca-Solana D, Gutiérrez-Zugasti I, Ruiz-Redondo A, et al. Painting Altamira Cave? Shell tools for ochre-processing in the Upper Palaeolithic in northern Iberia[J]. Journal of Archaeological Science, 2016, 74: 135-151 |

| [16] | Pitarch Martí A, Zilh?o J, d’Errico F, et al. The symbolic role of the underground world among Middle Paleolithic Neanderthals[J]. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 2021, 118: 33 |

| [17] | Bar-Yosef Mayer DE, Vandermeersch B, Bar-Yosef O. Shells and ochre in Middle Paleolithic Qafzeh Cave, Israel: indications for modern behavior[J]. Journal of Human Evolution, 2009, 56(3): 307-314 |

| [18] | Song YH, Cohen DJ, Shi JM. Diachronic change in the utilization of Ostrich Eggshell at the Late Paleolithic Shizitan Site, North China[J]. Frontiers in Earth Science, 2022 |

| [19] | Aldhouse-Green S, Pettitt P. Paviland Cave: contextualizing the ‘Red Lady’[J]. Antiquity, 1998, 72(278): 756-772 |

| [20] | Trinkets E, Buzhilova AP. The death and burial of sunghir 1[J]. International Journal of Osteoarchaeology, 2010, 22(6): 655-666 |

| [21] | Vanhaeren M, d’Errico F, Stringer C, et al. Middle Paleolithic shell beads in Israel and Algeria[J]. Science, 2006, 312(5781): 1785-1788 |

| [22] | Bouzouggar A, Barton N, Vanhaeren M, et al. 82,000-year-old shell beads from North Africa and implications for the origins of modern human behavior[J]. Anthropology, 2007, 104(24):9964-9969 |

| [23] | Wadley L, Hodgskiss T, Grant M. Implications for complex cognition from the hafting of tools with compound adhesives in the Middle Stone Age, South Africa[J]. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 2009, 106(24): 9590-9594 |

| [24] | Wojcieszak M, Wadley L. Raman spectroscopy and scanning electron microscopy confirm ochre residues on 71000-year-old bifacial tools from Sibudu, South Africa[J]. Archaeometry, 2018, 60(5): 1062-1076 |

| [25] | Villa P, Pollarolo L, Degano I, et al. A milk and ochre paint mixture used 49,000 years ago at Sibudu, South Africa[J]. PLoS One, 2015, 10(6): e0131273 |

| [26] | Zhang Y, Doyon L, Peng F, et al. An Upper Paleolithic perforated red deer canine with geometric engravings from QG10, Ningxia, Northwest China[J]. Frontiers in Earth Science, 2022, 10:814761 |

| [27] | Dayet L, d’Errico F, García-Diez M, et al. Critical evaluation of in situ analyses for the characterisation of red pigments in rock paintings: a case study from El Castillo, Spain[J]. PLoS One, 2022, 17(1): e0262143 |

| [28] | Kurniawan R, Kadja GTM, Setiawan P, et al. Chemistry of prehistoric rock art pigments from the Indonesian island of Sulawesi[J]. Microchemical Journal, 2019, 146: 227-233 |

| [29] | Dayet L, d’ Errico F, Garcia-Moreno R. Searching for consistencies in Chatelperronian pigment use[J]. Journal of Archaeological Science, 2014, 44: 180-193 |

| [30] | Maryanti E, Ilmi MM, Nurdini N, et al. Hematite as unprecedented black rock art pigment in Jufri Cave, East Kalimantan, Indonesia: the microscopy, spectroscopy, and synchrotron X-ray-based investigation[J]. Archaeological and Anthropological Sciences, 2022, 14: 122 |

| [31] | Rifkin RF, Prinsloo LC, Dayet L, et al. Charaterising pigments on 30 000-year-old portable art from Apollo 11 Cave, Karas Region, southern Namibia[J]. Journal of Archaeological Science: Reports, 2016, 5: 336-347 |

| [32] | Gomes H, Martins AA, Nash G, et al. Pigment in western Iberian schematic rock art: An analytical approach[J]. Mediterranean Archaeology and Archaeometry, 2015, 15(1) |

| [33] | Rigon C, Izzo FC, Pascual MLVDá, et al. New results in ancient Maya rituals researches: The study of human painted bones fragments from Calakmul archaeological site (Mexico)[J]. Journal of Archaeological Science: Reports, 2020, 32: 102418 |

| [34] | Hodgskiss T, Wadley L. How people used ochre at Rose Cottage Cave, South Africa: Sixty thousand years of evidence from the Middle Stone Age[J]. PLoS One, 2017, 12(4): e0176317 |

| [35] | Huntley J, Aubert M, Ross J, et al. One colour, (at least) two minerals: a study of mulberry rock art pigment and a mulberry pigment ‘quarry’ from the Kimberley, Northern Australia[J]. Archaeometry, 2015, 57(1): 77-99 |

| [36] | Behera PK, Thakur N. Late Middle Palaeolithic Red Ochre Use at Torajunga, an Open-Air Site in the Bargarh Upland, Odisha, India: Evidence for Long Distance Contact and Advanced Cognition[J]. Heritage: Journal of Multidisciplinary Studies in Archaeology, 2018, 6: 129-147 |

| [37] | Dayet L, Le Bourdonnec FX, Daniel F, et al. Ochre provenance and procurement strategies during the Middle Stone Age at Diepkloof Rock Shelter, South Africa[J]. Archaeometry, 2015, 58(5): 807-829 |

| [38] | Iriarte E, Foyo A, Sánchez MA, et al. The origin and geochemical characterization of red ochres from the Tito Bustillo and Monte Castillo Caves (Northern Spain)[J]. Archaeometry, 2009, 51(2): 231-251 |

| [39] | Moyo S, Mphuthi D, Cukrowska E, et al. Blombos Cave: Middle Stone Age ochre differentiation through FTIR, ICP OES, ED XRF and XRD[J]. Quaternary International, 2016, 404: 20-29 |

| [40] | Hovers E, Ilani Shimon, Bar-Yosef O, et al. An Early Case of Color Symbolism: Ochre Use by Modern Humans in Qafzeh Cave[J]. Current Anthropology, 2003, 44(4): 491-522 |

| [41] | Dayet Bouillot L, Wurz S, Daniel F. Ochre resources, behavioural complexity and regional patterns in the Howiesons Poort: new insights from Klasies River main site, South Africa[J]. Journal of African Archaeology, 2017, 15(1): 20-41 |

| [42] | Velliky EC, MacDonald BL, Porr M, et al. First large-scale provenance study of pigments reveals new complex behavioural patterns during the Upper Palaeolithic of south-western Germany[J]. Archaeometry, 2021, 63(1): 173-193 |

| [43] | Cavallo G, Fontana F, Gonzato F, et al. Sourcing and processing of ochre during the late upper Palaeolithic at Tagliente rock-shelter (NE Italy) based on conventional X-ray powder diffraction analysis[J]. Archaeological and Anthropological Sciences, 2017, 9: 763-775 |

| [44] | Darchuk L, Tsybrii Z, Worobiec A, et al. Argentinean prehistoric pigments’ study by combined SEM/EDX and molecular spectroscopy[J]. Spectrochimica Acta Part A: Molecular and Biomolecular Spectroscopy, 2010, 75(5): 1398-1402 |

| [45] | Charrié-Duhaut A, Porraz G, Cartwright C, et al. First molecular identification of a hafting adhesive in the Late Howiesons Poort at Diepkloof Rock Shelter (Western Cape, South Africa)[J]. Journal of Archaeological Science, 2012, 40(9): 3506-3518 |

| [46] | Dayet L, Texier PJ, Daniel F, et al. Ochre resources from the Middle Stone Age sequence of Diepkloof Rock Shelter, Western Cape, South Africa[J]. Journal of Archaeological Science, 2013, 40: 3492-3505 |

| [47] | Mortimore JL, Marshall LJR, Almond MJ, et al. Analysis of red and yellow ochre samples from Clearwell Caves and ?atalh?yük by vibrational spectroscopy and other techniques[J]. Spectrochimica Acta Part A Molecular and Biomolecular Spectroscopy, 2004, 60(5): 1179-1188 |

| [48] | Henshilwood CS, d’Errico F, van Niekerk KL, et al. An abstract drawing from the 73,000-year-old levels at Blombos Cave, South Africa[J]. Nature, 2018, 562: 115-118 |

| [49] | D’Errico F, Vanhaeren M, van Niekerk K, et al. Assessing the accidental versus deliberate colour modification of shell beads: a case study on perforated Nassarius kraussianus from Blombos Cave Middle Stone Age levels[J]. . Archaeometry, 57(1): 51-76 |

| [50] | Henshilwood CS, d’Errico F, van Niekerk KL, et al. A 100,000-year-old ochre-processing workshop at Blombos Cave, South Africa[J]. Science, 2011, 334(6053): 219-222 |

| [51] | Dayet L, Erasmus RM, Val A, et al. Beads, pigments and early Holocene ornamental traditions at Bushman Rock Shelter, South Africa[J]. Journal of Archaeological Science: Reports, 2017, 13(24): 635-651 |

| [52] | Langley MC, O’Connor S, Piotto E. 42,000-year-old worked and pigment-stained Nautilus shell from Jerimalai (Timor-Leste): Evidence for an early coastal adaptation in ISEA[J]. Journal of Human Evolution, 2016, 97: 1-16 |

| [53] | Peresani M, Vanhaeren M, Quaggiotto E, et al. An Ochered Fossil Marine Shell From the Mousterian of Fumane Cave, Italy[J]. PLoS One, 2013, 8(7): e68572 |

| [54] | Cortés-Sánchez M, Riquelme-Cantal JA, Simón-Vallejo MD, et al. Pre-Solutrean rock art in southernmost Europe: Evidence from Las Ventanas Cave (Andalusia, Spain)[J]. PLoS One 13(10): e0204651. |

| [55] | Pitarch Martí A, Wei Y, Gao X, et al. The earliest evidence of coloured ornaments in China: The ochred ostrich eggshell beads from Shuidonggou Locality 2[J]. Journal of Anthropological Archaeology, 2017, 48(1): 102-113 |

| [56] | Li ZY, Doyon L, Li H, et al. Engraved bones from the archaic hominin site of Lingjing, Henan Province[J]. Antiquity, 2019, 93(370): 886-900 |

| [57] | Pitarch Martí A, Zilh?o J, Mu?oz J R, et al. Geochemical characterization of the earliest Palaeolithic paintings from southwestern Europe: Ardales Cave, Spain[R]. The Art of Prehistoric Societies, VI Internacional Doctoral and Postdoctoral Meeting, 2019 |

| [58] | Ward I, Watchman A L, Cole N, et al. Identification of minerals in pigments from aboriginal rock art in the Laura and Kimberley regions, Australia[J]. Rock Art Research, 2001, 18(1): 15-23 |

| [59] | D’Errico F, Salomon H, Vjgnaud C, et al. Pigments from the Middle Palaeolithic levels of Es-Skhul (Mount Carmel, Israel)[J]. Journal of Archaeological Science, 2010, 37(12): 3099-3110 |

| [60] | Salomon H, Vignaud C, Lahlil S, et al. Solutrean and Magdalenian ferruginous rocks heat-treatment: acciental and/or deliberate action[J]. Journal of Archaeological Science, 2015, 55: 100-112 |

| [61] | Gialanella S, Belli R, Dalmeri G, et al. Artificial or natural origin of hematite-based red pigments in archaeological contexts: the case of Riparo Dalmeri(Ternto, Italy)[J]. Archaeometry, 2011, 53(5): 950-962 |

| [62] | Cavallo G, Fontana F, Gonzato F, et al. Textural, microstructural, and compositional characteristics of Fe-based geomaterials and Upper Paleolithic ocher in the Northeast Italy: implications for provenance studies[J]. Geoarchaeology, 2017, 32(4): 437-455 |

| [63] | Hunt A, Thomas P, James D, et al. The characterisation of pigments used in X-ray rock art at Dalakngalarr 1, central-western Arnhem Land[J]. Microchemical Journal, 2016, 126: 524-529 |

| [64] | De Faria DLA, Venancio Silva S, Raman microspectroscopy of some iron oxides and oxyhydroxides[J]. Journal of Raman Spectroscopy, 1997, 28(11): 873-878 |

| [65] | Bersani D, Lottici PP, Montenero A. Micro-Raman investigation of iron oxide films and powders produced by sol-gel syntheses[J]. Journal of Raman Spectroscopy, 1999, 30(5): 355-360 |

| [66] | Needham A, Croft S, Kr?ger R, et al. The application of micro-Raman for the analysis of ochre artefacts from Mesolithic palaeo-lake Flixton[J]. Journal of Archaeological Science: Reports, 2018, 17: 650-656 |

| [67] | Stuart BH, Thomas PS. Pigment characterisation in Australian rock art: a review of modern instrumental methods of analysis[J]. Heritage Science, 2017, 5: 10 |

| [68] | Wojcieszak M, Wadley L. A Raman micro-spectroscopy study of 77,000 to 71,000 year old ochre processing tools from Sibudu, KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa[J]. Heritage Science, 2019, 7: 24 |

| [69] | Texier PJ, Porraz G, Parkington J, et al. A Howiesons Poort tradition of engraving ostrich eggshell containers dated to 60,000 years ago at Diepkloof Rock Shelter, South Africa[J]. Anthropology, 2010, 107(14): 6180-6185 |

| [70] | Rosso DE, d’ Errico F, Queffelec A. Patterns of change and continuity in ochre use during the late Middle Stone Age of the Horn of Africa: The Porc-Epic Cave record[J]. PLoS One, 2017, 12(5): e0177298 |

| [71] | Lofrumento C, Ricci M, Bachechi L, et al. The first spectroscopic analysis of Ethiopian prehistoric rock painting[J]. Journal of Raman Spectroscopy, 2011, 43(6): 809-816 |

| [72] | 刘青松, 邓成龙, 潘永信. 磁铁矿和磁赤铁矿磁化率的温度和频率特性及其环境磁学意义[J]. 第四纪研究, 2007, 27(6): 955-962 |

| [73] | Stacey FD, Banerjee SK. The physical principles of rock magnetism[M]. Amsterdam: Elsevier, 1974, 1-195 |

| [74] | Mooney SD, Geiss C, Smith MA. The use of mineral magnetic parameters to characterize archaeological ochres[J]. Journal of Archaeological Science, 2003, 30(5): 511-523 |

| [75] | McPherron SP. Lithics[M]. Richards MP, Britton K. Archaeological Science: an Introduction. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. 2020: 387-404 |

| [76] | 赵丛苍. 科技考古学概论[M]. 北京: 高等教育出版社, 2018: 291-359 |

| [77] | MacDonald BL, Hancock RGV, Cannon A, et al. Geochemical characterization of ochre from central coastal British Columbia, Canada[J]. Journal of Archaeological Science, 2011, 38(12): 3620-3630 |

| [78] | MacDonald BL, Hancock RGV, Cannon A, et al. Elemental analysis of ochre outcrops in southern British Columbia, Canada[J]. Archaeometry, 2013, 55(6): 1020-1033 |

| [79] | Popelka-Filcoff RS, Robertson JD, Glascock MD, et al. Trace element characterization of ochre from geological sources[J]. Journal of Radioanalytical and Nuclear Chemistry, 2007, 272(1): 17-27 |

| [80] | Popelka-Filcoff RS, Miksa EJ, Robertson JD, et al. Elemental analysis and characterization of ochre sources from southern Arizona[J]. Journal of Archaeological Science, 2008, 35(3): 752-762 |

| [81] | 乔治 R, 克里斯托弗 LH.地质考古学:地球科学方法在考古学中的应用[M]. 译者:杨石霞,赵克良,李小强. 北京: 科学出版社, 2020 |

| [82] | 伦福儒 C, 巴恩 P. 考古学:理论方法与实践[M]. 译者:陈淳. 第6版. 上海: 上海古籍出版社, 2015 |

| [83] | 王德滋, 谢磊. 光性矿物学[M]. 北京: 科学出版社, 2008: 1-26 |

| [84] | Erlandson JM, Robertson JD, Descantes C. Geochemical analysis of eight red ochres from western North America[J]. American Antiquity, 1999, 64(3): 517-526 |

| [85] | Jacobs Z, Roberts RG, Galbraith RF, et al. Ages for the Middle Stone Age of southern Africa: implications for human behavior and dispersal[J]. Science, 2008, 322(5902): 733-735 |

| [86] | Chase BM. South African palaeoenvironments during marine oxygen isotope stage 4: a context for the Howiesons Poort and Still Bay industries[J]. Journal of Archaeological Science, 2010, 37(6): 1359-1366 |

| [87] | Mackay A. Nature and significance of the Howiesons Poort to post-Howiesons Poort transition at Klein Kliphuis rockshelter, South Africa[J]. Journal of Archaeological Science, 2011, 38(7): 1430-1440 |

| [88] | Porraz G, Texier PJ, Archer W, et al. Technological successions in the Middle Stone Age sequence of Diepkloof Rock Shelter, Western Cape, South Africa[J]. Journal of Archaeological Science, 2013, 40(9): 3376-3400 |

| [89] | Tobias PV. From tools to symbols: from early hominids to modern humans[M]. In:d’Errico F and Backwell L(eds). Johannesburg: Wits University Press, 2005 |

| [90] | Rifkin RF. The symbolic and functional exploitation of ochre during the South African Middle Stone Age[M]. Johannesburg: Wits University Press, 2013 |

| [91] | Wreschner EE, Bolton R, Butzer KW, et al. Red ochre and human evolution: a case for discussion[J]. Current Anthropology, 1980, 21(5): 631-644 |

| [92] | Mcbrearty S, Brooks AS. The revolution that wasn't: a new interpretation of the origin of modern human behavior[J]. Journal of Human Evolution, 2000, 39(5): 453-563 |

| [93] | Keeley LH. Experimental determination of stone tool uses[M]. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 1980 |

| [94] | Rifkin RF. Processing ochre in the Middle Stone Age: testing the inference of prehistoric behaviours from actualistically derived experimental data[J]. Journal of Anthropological Archaeology, 2012, 31(2): 174-195 |

| [95] | Hodgskiss T. Ochre use in the Middle Stone Age[J]. Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Anthropology, 2020 |

| [96] | Kozowyk PRB, Langejans GHJ, Poulis JA. Lap Shear and impact testing of ochre and beeswax in experimental Middle Stone Age compound adhesives[J]. PLoS One, 2016, 11(3): e0150436 |

| [97] | Siddall R. Mineral pigments in archaeology: Their analysis and the range of available materials. Minerals, 2018, 8(5): 201 |

| [98] | Ismunandar, Nurdini N, Ilmi MM, et al. Investigation on the crystal structures of hematite pigments at different sintering temperatures[J]. Key Engineering Materials, 2021, 874: 20-27 |

| [99] | 靳桂云. 土壤微形态分析及其在考古学中的应用[J]. 地球科学进展, 1999, 14(2): 197-200 |

| [100] | 张海, 庄奕杰, 方燕明, 等. 河南禹州瓦店遗址龙山文化壕沟的土壤微形态分析[J]. 华夏考古, 2016, 4: 86-95, I0009-I0014 |

| [101] | 魏屹, d'Errico F, 高星. 旧石器时代装饰品研究:现状与意义[J]. 人类学学报, 2016, 35(1): 132-148 |

| [102] | Klein RG. Out of Africa and the evolution of human behavior[J]. Evolutionary Anthropology: Issues, News, and Reviews, 2008, 17(6): 267-281 |

| [103] | 黄淑娉, 龚佩华. 文化人类学理论方法研究(第3版)[M]. 广州: 广东高等教育出版社, 2004 |

| [104] | 庄孔韶. 人类学通论[M]. 太原: 山西教育出版社, 2005 |

| [105] | Scott DA, Scheerer S, Reeves DJ. Technical examination of some rock art pigments and encrustations from the Chumash Indian site of San Emigdio, California[J]. Studies in Conservation, 2002, 47(3): 184-194 |

| [106] | D’Errico F, Vanhaeren M. Evolution or Revolution? New evidence for the origin of symbolic behaviour in and out of Africa[M]. Mellars P, Boyle K, Bar-Yosef O, et al. Rethinking the human revolution: new behavioural and biological perspectives on the origin and dispersal of modern humans[C]. Cambridge: McDonald Institute for Archaeological Research, 2007: 257-286 |

| [107] | Wang C, Lu HY, Zhang JP, et al. Prehistoric demographic fluctuations in China inferred from radiocarbon data and their linkage with climate change over the past 50,000 years[J]. Quaternary Science Reviews, 2014, 98: 45-59 |

| [108] | Feng Y, Wang Y. The environmental and cultural contexts of early pottery in south China from the perspective of behavioral diversity in the Terminal Pleistocene[J]. Quaternary International, 2022, 608-609: 33-48 |

| [109] | Yang SX, Zhang YX, Li YQ, et al. Environmental change and raw material selection strategies at Taoshan: a terminal Late Pleistocene to Holocene site in north-eastern China[J]. Journal of Quaternary science, 2017, 32(5): 553-563 |

| [110] | Bae CJ, Douka K, Petraglia MD. On the origin of modern humans: Asian perspectives[J]. Science, 2017, 358(6368): eaai9067. |

| [111] | Rifkin RF. Ethnographic insight into the prehistoric significance of red ochre[J]. Digging stick, 2015, 32(2): 7-10 |

| [112] | Huntley J. Australian Indigenous Ochres: Use, Sourcing, and Exchange[A]. In: Ian J, Bruno D(Eds). The Oxford Handbook of the Archaeology of Indigenous Australia and New Guinea[C]. Oxford University Press, 2018, 1-33 |

/

| 〈 |

|

〉 |