An excavation report of the Shuidonggou Locality 9, Ningxia

Received date: 2024-01-08

Accepted date: 2024-05-29

Online published: 2025-04-15

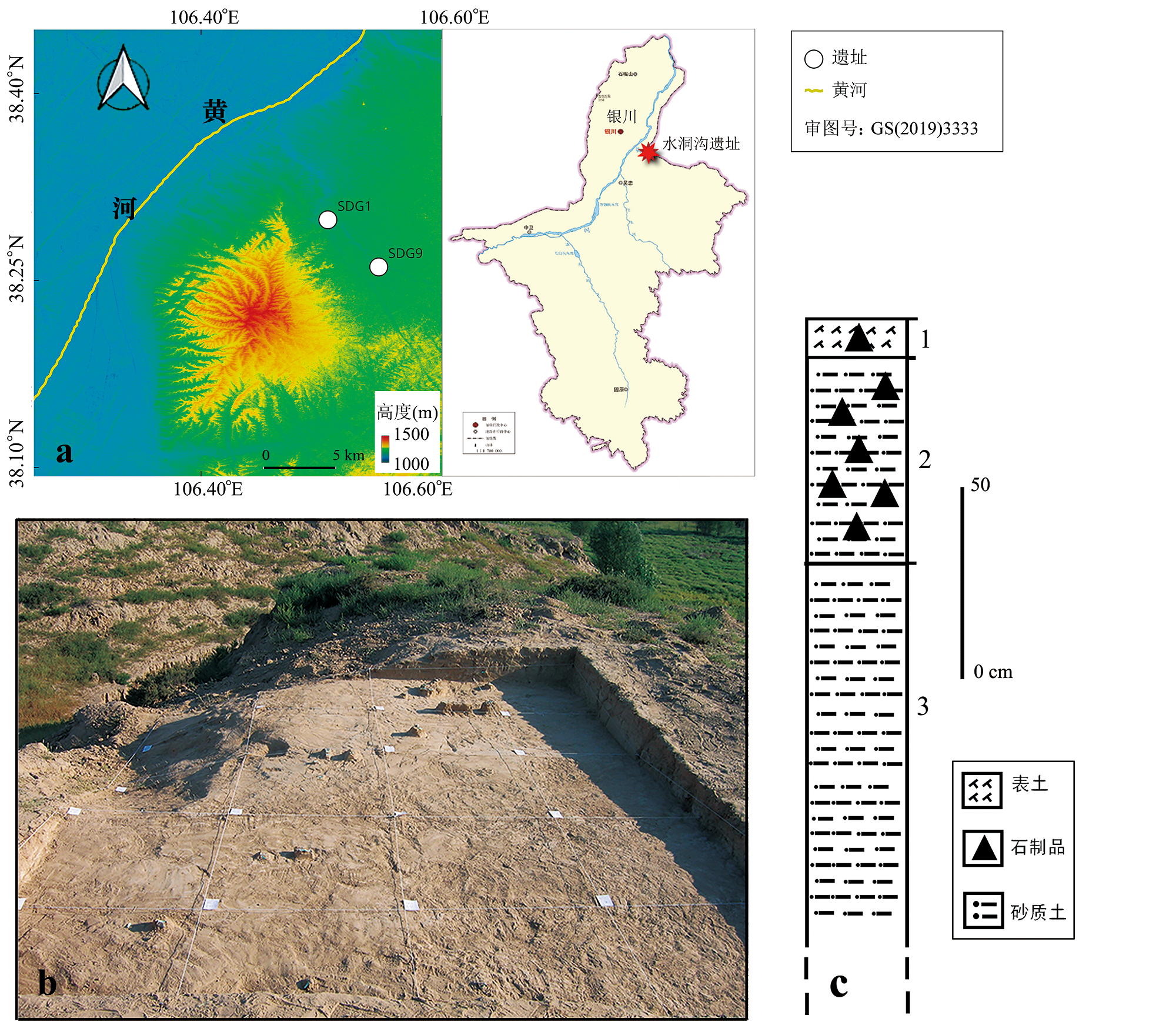

In 2007, the Institute of Vertebrate Paleontology and Paleoanthropology of the Chinese Academy of Sciences, in collaboration with the Ningxia Institute of Archaeology and Cultural Relics, initiated a formal excavation at Shuidonggou Locality 9. The excavation uncovered an area of 20 m2, revealing relatively thin cultural deposits that were situated directly beneath the surface soil layer. Over the course of the excavation, a total of 414 lithic artifacts were unearthed from this cultural layer. These findings suggest that while the lithic artifacts at SDG9 were largely in-situ burials, they had experienced some degree of post-depositional disturbance over time. A detailed analysis of the lithic assemblage revealed cultural characteristics at this site that were strikingly similar to those documented at SDG1, indicating a shared technological tradition. The predominant raw material used in the lithic assemblage was siliceous limestone, reflecting the local availability of resources and suggesting a pattern of raw material exploitation focused on efficiency. In addition to simple core-flake technology, researchers uncovered evidence of a more sophisticated technique involving the systematic production of elongated flakes and blades from prepared cores using hard hammer percussion. This advanced production method points to a deliberate technological choice aimed at maximizing material utility and reflects a highly organized approach to lithic reduction. Furthermore, artifacts related to bladelet production were also identified, providing valuable insights into the diversity of technological practices at the site. However, only three formal stone tools were recovered from the assemblage, suggesting a relatively narrow range of tool types present. Luminescence dating of the cultural layer yielded an approximate age of 29,000 years, although it was suggested that this date may have been underestimated due to the shallow burial of the artifacts, which may have led to some post-depositional alterations. The discovery of the SDG9 lithic assemblage provides yet another important example of blade production technology, closely resembling that documented at SDG1 and characteristic of Initial Upper Paleolithic (IUP) technology in this region. Despite the overall similarities, the SDG9 assemblage exhibits differences from SDG1, most notably the absence of prismatic and sub-prismatic cores, as well as fewer retouched pieces. Such disparities likely indicate regional variations and diversities in IUP assemblages across different sites at Shuidonggou. These findings contribute valuable material for advancing the study of blade technology in northern China, examining the cultural attributes associated with the Initial Upper Paleolithic, and shedding light on the broader behavioral evolution of prehistoric human populations inhabiting arid regions.

Key words: Shuidonggou site; archeological excavation; stone artifact; blade

PENG Fei , CHEN Guo , PEI Shuwen , WANG Huimin , GAO Xing . An excavation report of the Shuidonggou Locality 9, Ningxia[J]. Acta Anthropologica Sinica, 2025 , 44(02) : 283 -294 . DOI: 10.16359/j.1000-3193/AAS.2024.0089

| [1] | Bo?da E, Hou YM, Forestier H, et al. Levallois and non-Levallois blade production at Shuidonggou(Province of Ningxia, North China)[J]. Quaternary International, 2013, 295: 191-203 |

| [2] | Peng F, Wang H, Gao X. Blade production of Shuidonggou Locality 1 (Northwest China): a technological perspective[J]. Quaternary International, 2014, 347: 12-20 |

| [3] | Li F, Kuhn SL, Chen F, et al. Intra-assemblage variation in the macro-blade assemblage from the 1963 excavation at Shuidonggou locality 1, northern China, in the context of regional variation[J]. PLOS ONE, 2020, 15(6): e0234576 |

| [4] | 宁夏回族自治区文物考古研究所, 中国科学院古脊椎动物与古人类研究所. 水洞沟2003-2007年度考古发掘与研究报告[M]. 北京: 科学出版社, 2013 |

| [5] | Madsen DB, Oviatt CG, Zhu Y, et al. The early appearance of Shuidonggou core-and-blade technology in north China: Implications for the spread of Anatomically Modern Humans in northeast Asia?[J]. Quaternary International, 2014, 347: 21-28 |

| [6] | Li F, Kuhn SL, Gao X, et al. Re-examination of the dates of large blade technology in China: A comparison of Shuidonggou Locality 1 and Locality 2[J]. Journal of Human Evolution, 2013, 64(2): 161-168 |

| [7] | Niu D, Pei S, Zhang S, et al. The Initial Upper Palaeolithic in Northwest China: New evidence of cultural variability and change from Shuidonggou locality 7[J]. Quaternary International, 2016, 400: 111-119 |

| [8] | 高星, 裴树文, 王惠民, 等. 宁夏旧石器考古调查报告[J]. 人类学学报, 2004, 23(4): 307-325 |

| [9] | Pei S, Gao X, Wang H, et al. The Shuidonggou site complex: new excavations and implications for the earliest Late Paleolithic in North China[J]. Journal of Archaeological Science, 2012, 39(12): 3610-3626 |

| [10] | Li L, Lin SC, Peng F, et al. Simulating the impact of ground surface morphology on archaeological orientation patterning[J]. Journal of Archaeological Science, 2021, 126: 105310 |

| [11] | 彭菲. 中国北方旧石器时代石叶技术研究:以水洞沟与新疆材料为例[D]. 博士研究生论文, 北京: 中国科学院研究生院, 2012, 86-90 |

| [12] | 王社江. 洛南花石浪龙牙洞1995年出土石制品的拼合研究[J]. 人类学学报, 2005, 24(1): 1-17 |

| [13] | Schick KD. Stone Age sites in the making: experiments in the formation and transformation of archaeological occurrences[D]. Oxford: British Archaeological Reports, International Series 319, 1986 |

| [14] | 宁夏文物考古研究所. 水洞沟:1980年发掘报告[M]. 北京: 科学出版社, 2003 |

| [15] | Derevianko AP, Shimkin DB, Power WR(eds). The Paleolithic of Siberia: new discoveries and interpretations[M]. Chicago: University of Illinois Press, 1998 |

| [16] | Shimelmitz R, Barkai R, Gopher A. Systematic blade production at late lower Paleolithic (400-200 kyr) Qesem Cave, Israel[J]. Journal of Human Evolution, 2011, 61(4): 458-479 |

| [17] | Soriano S, Villa P, Wadley L. Blade technology and tool forms in the Middle Stone Age of South Africa: the Howiesons Poort and post-Howiesons Poort at rose Cottage Cave[J]. Journal of Archaeological Science, 2007, 34(5): 681-703 |

| [18] | Meignen L. Levantine perspectives on the Middle to Upper Paleolithic “transition”[J]. Archaeology, Ethnology and Anthropology of Eurasia, 2012, 40(3): 12-21 |

| [19] | Morgan C, Barton L, Yi M, et al. Redating shuidonggou locality 1 and implications for the initial upper paleolithic in East Asia[J]. Radiocarbon, 2014, 56(1): 165-179 |

| [20] | Peng F, Lin SC, Patania I, et al. A chronological model for the late paleolithic at shuidonggou locality 2, North China[J]. PLOS ONE, 2020, 15(5): e0232682 |

| [21] | Nian X, Gao X, Zhou L. Chronological studies of Shuidonggou (SDG) Locality 1 and their significance for archaeology[J]. Quaternary International, 2014, 347: 5-11 |

/

| 〈 |

|

〉 |