A taphonomic study of early Pleistocene mammalian assemblages from the Chuifeng Cave site in South China

Received date: 2024-12-19

Revised date: 2025-03-11

Online published: 2025-06-18

Caves in South China yield abundant and well-preserved vertebrate fossils, which provide a significant foundation for the study of Quaternary biostratigraphy, species evolution, and palaeoecology. These fossils offer crucial insights into the exploration of human evolution and activities. However, the origin, burial processes, and characteristics of cave fossils in South China have not been sufficiently explored. This insufficiency impedes a comprehensive understanding of the taphonomic processes of fauna assemblages across different temporal periods in the region.

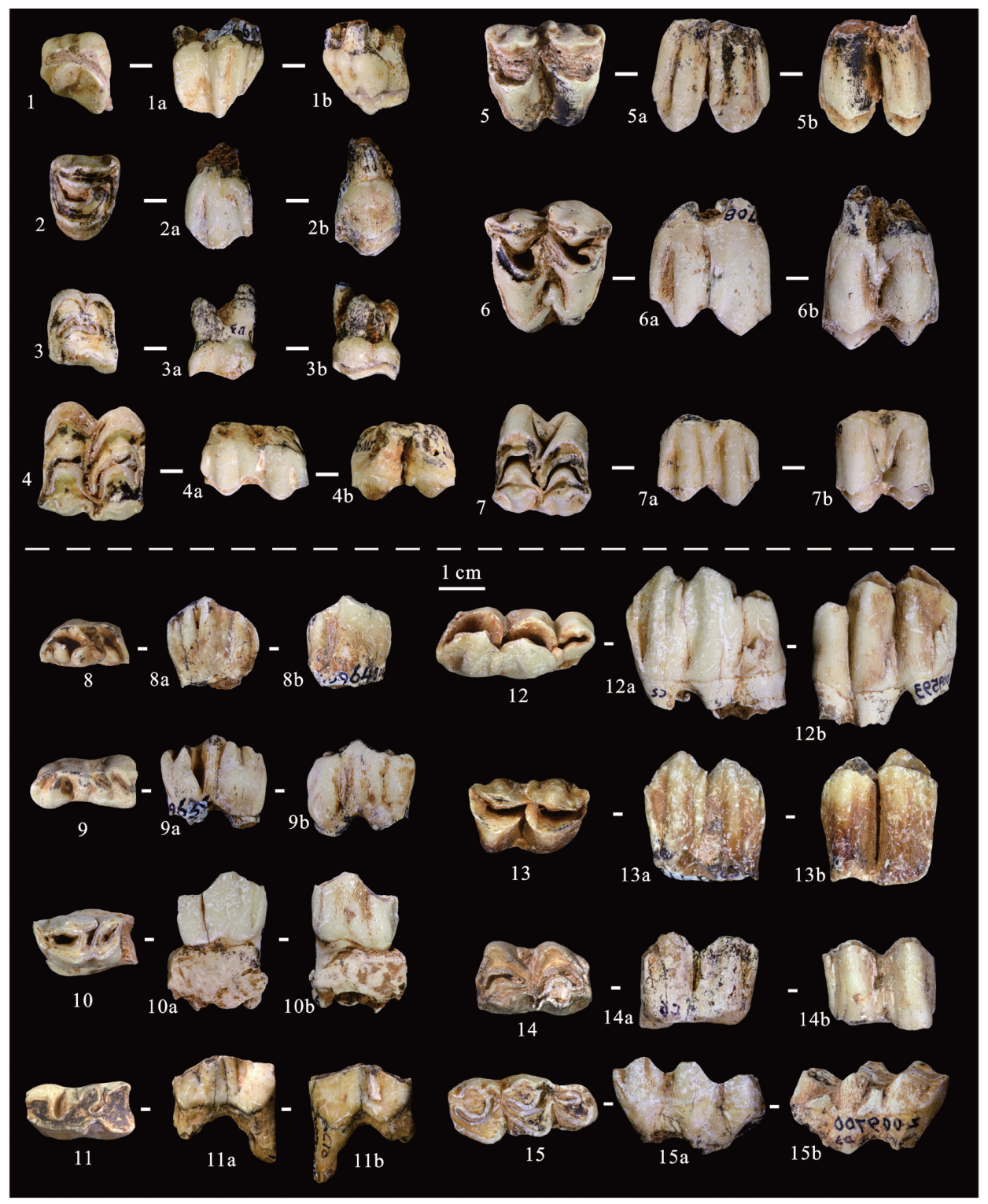

This study presents a detailed analysis of the burial characteristics of nearly 1,000 fossil mammalian teeth and fragmented bones unearthed from the Early Pleistocene Chuifeng Cave site (ca. 1.9 MaBP) in the Bubing Basin, Guangxi. The age-at-death was determined by the degree of tooth abrasion of the dominant populations, and the causes of death were analyzed based on the mortality patterns of the species.

The mortality profile of rhinos shows an attritional pattern, with fewer sub-adults. This is likely the result of both natural mortality and predation. In addition, the mortality profiles of cervids and suids exhibit a prime-dominated structure, which is usually associated with human hunting. However, since no human fossils have been found at the Chuifeng Cave site and no remains of human activities from this period have been found in the Bubing Basin, it is possible that the mortality profiles of these species are the result of a combination of factors.

The gnawing marks on the surface of the fossils suggest that the death of the dominant population could have been due to predation or natural death. The gnawing marks could have been caused either by a predator’s (e.g., hyena) consumption or handling or by porcupines collecting bones. The varying degrees of rounding and weathering marks on the surface of the fossils indicate that the accumulation of faunal bones was not a one-off burial following a disaster. This further demonstrates that the phenomenon may have been a relatively slow burial process resulting from natural death or predation by carnivores.

The present case-study of the taphonomy of Chuifeng Cave provides an important reference for re-conceptualizing the origin and accumulation process of fossils from caves in South China. Admittedly, there are numerous fossil-producing caves in South China, with diverse accumulation conditions and complex causes. Further in-depth studies are needed to comprehensively reveal the burial characteristics of South China’s caves and to lay an important foundation for paleoanthropological research.

YAO Yanyan , HUANG Shengmin , LIAO Wei , LI Jinyan , ZHANG Yijing , MO Jinyou , WANG Wei . A taphonomic study of early Pleistocene mammalian assemblages from the Chuifeng Cave site in South China[J]. Acta Anthropologica Sinica, 2025 , 44(03) : 514 -528 . DOI: 10.16359/j.1000-3193/AAS.2025.0033

| [1] | Bacon AM, Duringer P, Antoine PO, et al. The Middle Pleistocene mammalian fauna from Tam Hang karstic deposit, northern Laos: New data and evolutionary hypothesis[J]. Quaternary International, 2011, 245: 315-332 |

| [2] | Duringer P, Bacon AM, Sayavongkhamdy T, et al. Karst development, breccias history, and mammalian assemblages in Southeast Asia: A brief review[J]. Science Direct, 2012, 11: 133-157 |

| [3] | Fan YB, Shao QF, Bacon AM, et al. Late Pleistocene large-bodied mammalian fauna from Mocun cave in south China: Palaeontological, chronological and biogeographical implications[J]. Quaternary Science Reviews, 2022, 294: 107741 |

| [4] | Liang H, Liao W, Shao QF, et al. New discovery of a late Middle Pleistocene mammalian fauna in Ganxian Cave, Southern China[J]. Historical Biology, 2022, 1-18 |

| [5] | Liao W, Harrison T, Yao YY, et al. Evidence for the latest fossil Pongo in southern China[J]. Journal of Human Evolution, 2022, 170: 103233 |

| [6] | Vu T L, Vos JD, Ciochon RL. The fossil mammal fauna of the Lang Trang caves, Vietnam, compared with Southeast Asian fossil and recent mammal faunas: the geographical implications[J]. Bulletin of the Indo-Pacific Prehistory Association, 1996, 14: 100-109 |

| [7] | Wang W, Liao W, Li DW, et al. Early Pleistocene large-mammal fauna associated with Gigantopithecus at Mohui Cave, Bubing Basin, South China[J]. Quaternary International, 2014, 354: 122-130 |

| [8] | Yao YY, Fan YB, Bae CJ, et al. Early Mid-Pleistocene mammal fauna from Yanlidong Cave, South China[J]. Historical biology, 2023, 1-18 |

| [9] | Christopher J.B, Wang W, Zhao JX, et al. Modern human teeth from Late Pleistocene Luna Cave (Guangxi, China)[J]. Quaternary International, 2014, 354: 169-183 |

| [10] | Liao W, Xing S, Li DW, et al. Mosaic dental morphology in a terminal Pleistocene hominin from Dushan Cave in southern China[J]. Scientific Reports, 2019, 9(1): 1-14 |

| [11] | Yao YY, Liao W, Christopher J.B, et al. New discovery of Late Pleistocene modern human teeth from Chongzuo, Guangxi, southern China[J]. Quaternary International, 2020, 563: 5-12 |

| [12] | 金昌柱, 潘文石, 张颖奇, 等. 广西崇左江州木榄山智人洞古人类遗址及其地质时代[J]. 科学通报, 2009, 54(19): 2848-2856 |

| [13] | 王頠, Potts R, 侯亚梅, 等. 广西布兵盆地么会洞新发现的早更新世人类化石[J]. 科学通报, 2005, 17: 85-89 |

| [14] | Tong HW, Zhang SQ, Chen FY, et al. Rongements sélectifs des os par les porcs-épics et autres rongeurs: cas de la grotte Tianyuan, un site avec des restes humains fossiles récemment découvert près de Zhoukoudian (Choukoutien)[J]. L'Anthropologie, 2008, 112(3): 353-369 |

| [15] | Tong HW. Age Profiles of Rhino Fauna from the Middle Pleistocene Nanjing Man Site, South China -Explained by the Rhino Specimens of Living Species[J]. International Journal of Osteoarchaeology, 2001, 11: 231-237 |

| [16] | Schepartz LA, Stoutamire S, Bekken DA. Stegodon orientalis from Panxian Dadong, a Middle Pleistocene archaeological site in Guizhou, South China: taphonomy, population structure and evidence for human interactions[J]. Quaternary International, 2005, (126-128): 271-282 |

| [17] | Schepartz LA, Miller-Antonio S. Taphonomy, Life History, and Human Exploitation of Rhinoceros sinensis at the Middle Pleistocene Site of Panxian Dadong, Guizhou, China[J]. International Journal of Osteoarchaeology, 2010, 20: 253-268 |

| [18] | 李占扬, 张双权. 灵井遗址动物群埋藏学研究方法与思路[J]. 中原文物, 2008, 5: 26-32 |

| [19] | 张双权, 李占扬, 张乐, 等. 河南灵井许昌人遗址大型食草类动物死亡年龄分析及东亚现代人类行为的早期出现[J]. 科学通报, 2009, 54(19): 2857-2863 |

| [20] | 陈曦, 同号文. 泥河湾山神庙嘴化石点直隶狼埋藏学研究[J]. 人类学学报, 2015, 34(4): 553-564 |

| [21] | 陈君, 王頠, 李大伟, 等. 广西田东中山遗址洞外岩厦出土动物骨骼的初步研究[J]. 人类学学报, 2017, 36(4): 527-536 |

| [22] | Bacon AM, Westaway K, Antoine PO, et al. Late Pleistocene mammalian assemblages of Southeast Asia: New dating,mortality profiles and evolution of the predator-prey relationships in an environmental context[J]. Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology, 2015, 422: 101-127 |

| [23] | Wang W. New discoveries of Gigantopithecus blacki teeth from Chuifeng Cave in the Bubing Basin, Guangxi, south China[J]. Journal of Human Evolution, 2009, 57(3): 229-240 |

| [24] | Wang W, Potts R, Yuan BY, et al. Sequence of mammalian fossils, including hominoid teeth, from the Bubing Basin caves, South China[J]. Journal of Human Evolution, 2007, 52(4): 370-379 |

| [25] | Shao QF, Wang W, Deng CL, et al. ESR, U-series and paleomagnetic dating ofGigantopithecus fauna from Chuifeng Cave, Guangxi, southern China[J]. Quaternary Research, 2014, 82(1): 270-280 |

| [26] | Welker F, Ramos-Madrigal J, Kuhlwilm M, et al. Enamel proteome shows that Gigantopithecus was an early diverging pongine[J]. Nature, 2019, 576(7786): 262-265 |

| [27] | Zhang YQ, Westaway KE, Haberle S, et al. The demise of the giant ape Gigantopithecus blacki[J]. Nature, 2024, 625: 535-539 |

| [28] | 李大伟, 王伟, 胡超涌, 等. 广西更新世早期吹风洞的古环境——来自巨猿动物群牙釉质C、O同位素的证据[J]. 第四纪研究, 2021, 41(5): 1357-1365 |

| [29] | Liao W, Liang H, Li JY, et al. Early Pleistocene large-mammal assemblage associated with Gigantopithecus at Chuifeng Cave Bubing Basin South China[J]. Historical Biology, 2023, 3: 1-18 |

| [30] | Brown WAB. The dentition of red deer (Cervus elaphus): a scoring scheme to assess age from wear of the permanent molariform teeth[J]. The Zoological Society of London, 1991, 224: 519-536 |

| [31] | 张明海, 许庆翔, 路秉信, 等. 马鹿臼齿磨损率与年龄关系的研究[J]. 兽类学报, 2000, 20(4): 250-257 |

| [32] | Smith H. Age estimation of the White rhinoceros Ceratotherium simum[J]. Journal of Zoology, 1986, 210: 355-379 |

| [33] | Stiner MC. The Use of Mortality Patterns in Archaeological Studies of Hominid Predatory Adaptations[J]. Journal of Anthropological Archaeology, 1990, 9: 305-351 |

| [34] | 李青, 同号文. 周口店田园洞梅花鹿年龄结构分析[J]. 人类学学报, 2008, 27(2): 141-150 |

| [35] | Rolett BV, Chiu MY. Age Estimation of Prehistoric Pigs (Sus scrofa) by Molar Eruption and Attrition[J]. Journal of Archaeological Science, 1994, 21: 377-386 |

| [36] | Wilson B, Grigson C, Payne S. Ageing and sexing animal bones from archaeological sites[M]. England: BAR British Series, 1982 |

| [37] | 严亚玲, 金昌柱, 朱敏, 等. 广西扶绥岩亮洞早更新世独角犀年龄结构的分析[J]. 人类学学报, 2014, 33(4): 534-544 |

| [38] | Voorhies M. Taphonomy and population dynamics of an early Pliocene vertebrate fauna, Knox County, Nebraska[J]. Contributions to geology Special paper, 1969, 1-69 |

| [39] | 张双权, Christopher JN, 张乐. 考古动物群中的偏移现象——埋藏学的视角[J]. 人类学学报, 2007, 4: 379-388 |

| [40] | Behrensmeyer AK. Taphonomic and ecologic information from bone weathering[J]. Paleobiology, 1978, 4(2): 150-162 |

| [41] | 刘金毅. 繁昌人字洞与硕鬣狗漫谈[J]. 化石, 2018, 4: 26-32 |

| [42] | Brank CK. The hunters or the hunted? An introduction to African cave taphonomy[M]. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1981 |

| [43] | 曲彤丽. 旧石器时代埋藏学[M]. 北京: 北京大学出版社, 2022 |

| [44] | 王頠. 广西田东么会洞早更新世人猿超科化石及其在早期人类演化研究上的意义[D]. 博士研究生毕业论文, 武汉: 中国地质大学, 2005 |

| [45] | Steele TE, Weaver TD. The Modified Triangular Graph: A Refined Method for Comparing Mortality Profiles in Archaeological Samples[J]. Journal of Archaeological Science, 2002, 29(3): 317-322 |

| [46] | Lemine G. Morlan RE. Spiral fractures on limb bones: which ones are artificial?[M]. In: MacEachern A(eds). Carnivores, Human Scavengers and Predators: A Question of Bone Technology[M]. Calgary: The Archaeological Association of The University of Calgary, 1983 |

| [47] | Munson PJ. Age-correlated differential destruction of bones and its effect on archaeological mortality profiles of domestic sheep and goats[J]. Journal of Archaeological Science, 2000, 27: 391-407 |

| [48] | Kahlke RD, Gaudzinski S. The blessing of a great flood: differentiation of mortality patterns in the large mammal record of the Lower Pleistocene fluvial site of Untermassfeld (Germany) and its relevance for the interpretation of faunal assemblages from archaeological sites[J]. Journal of Archaeological Science, 2005, 32: 1202-1222 |

| [49] | Bacon AM, Demeter F, Duringe P, et al. The Late Pleistocene Duoi U’Oi cave in northern Vietnam: palaeontology, sedimentology, taphonomy and palaeoenvironments[J]. Quaternary Science Reviews, 2008, 27(15): 1627-1654 |

| [50] | 武仙竹, 李禹阶, 裴树文, 等. 湖北郧西白龙洞遗址骨化石表面痕迹研究[J]. 第四纪研究, 2008, 6: 1023-1033 |

/

| 〈 |

|

〉 |