Mammalian astragalus fossils excavated at Hualongdong site

Received date: 2025-05-06

Revised date: 2025-07-18

Online published: 2025-10-13

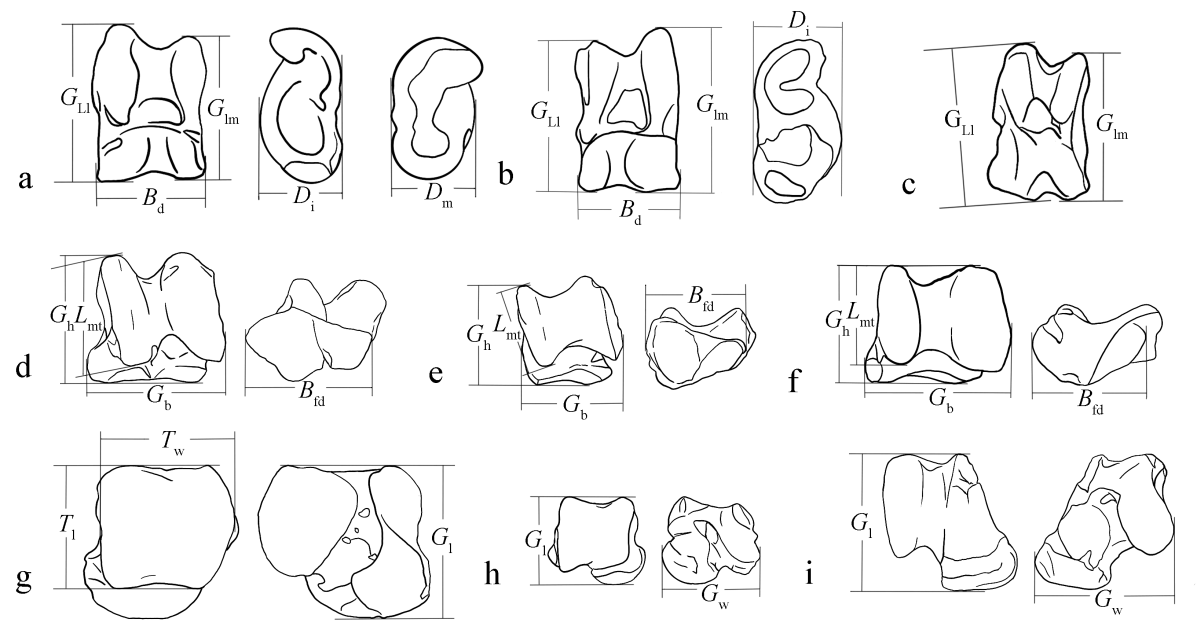

The astragalus is one of the tarsal bones and anatomically subdivided into three distinct regions: the head, neck, and body. This critical bone serves as the primary osseous interface between the distal tibia and proximal tarsal bones, forming the talocrural articulation that facilitates the characteristic hinge-like motion of the tetrapod ankle joint. Furthermore, comparative osteological analyses reveal that the astragalus typically exhibits greater structural density compared to other skeletal elements, a morphological adaptation likely associated with its weight-bearing function within the ankle complex. This increased bone density, combined with its strategic anatomical position protected by adjacent articulating surfaces, significantly enhances its preservation potential in both modern and paleontological contexts. The exceptional preservation frequency of astragali in vertebrate fossil records has consequently established this element as a crucial anatomical marker for phylogenetic studies and functional morphology analyses. In addition, since the structure of the astragalus is directly related to the locomotion patterns of animals and reflects the range of motion of the hind limbs, it is often used to analyze the characteristics of species and their ecological and functional adaptability. The Hualongdong Site is an important comprehensive ancient human site from the late Middle Pleistocene in China, where a large number of mammalian fossils have been unearthed. This paper takes 316 specimens of mammalian astragalus fossils excavated at the site from 2014 to 2024 as research materials. The investigation methodologically integrates the measurement, the identification of morphological characteristics and the analysis of surface traces, This systematic approach facilitates a comprehensive exploration of the animal group, the ancient human behaviors, and the background of burial. The mammalian astragalus bones unearthed at the Hualongdong reflect a fauna composition dominated by the Cervidae and the Bovidae, accounting for 84.5% of the identifiable specimens and 80.5% of the minimum number of individuals respectively. Sus lydekkeri and carnivores, predominantly from the Ursidae also account for a certain number. There are also a few specimens from the Rhinocerotidae, Equidae, Tapiridae and Stegodontidae. The presence of the austral Ailuropoda-Stegodon faunal elements is represented by Ailuropda, Stegodontidae, and Tapiridae, while the presence of boreal taxa is represented by Cervus (Sika) grayi, Equidae, Stephanorhinus sp. In fact, the NISP and MNI of the boreal taxa are higher than the austral taxa. The astragalus measurement data show that Bos (Bibos) sp., Equidae, Rhiocerotidae, and Sus lydekkeri at the Hualongdong site represent the larger body sizes comparative to their relatives during the same period. Overall, the composition of the animal group reflected by the astragalus indicates a relatively open forest-grassland landform, with the presence of mountain animals. Burial analysis indicates that the astragalus is less affected by natural forces such as weathering and erosion by water flow. A thorough examination of the surface marks reveals that the astragali of the Cervidae and Bovidae families exhibited artificial cutting marks, chopping marks, carnivorous biting marks, and rodent gnawing marks. This indicates the involvement of humans, carnivores, and rodents in the accumulation of astragali in the cave. This study is the first to systematically reveals the composition of the animal group and the evidence of human behavior reflected by the astragalus fossils at the Hualongdong site. It provides reference materials for the research on the survival strategies and animal resource utilization of ancient humans in East Asia during the late Middle Pleistocene.

LIU Sitong , LIU Boxuan , JIN Zetian , DENG Guodong , TONG Haowen , WU Xiujie . Mammalian astragalus fossils excavated at Hualongdong site[J]. Acta Anthropologica Sinica, 2025 , 44(05) : 816 -835 . DOI: 10.16359/j.1000-3193/AAS.2025.0072

| [1] | Wang M, Zhou Z. Low morphological disparity and decelerated rate of limb size evolution close to the origin of birds[J]. Nat Ecol Evol, 2023, 7: 1257-1266 |

| [2] | Lewis OJ. The joints of the evolving foot. Part I. The ankle joint[J]. Journal of anatomy, 1980, 130(3): 527-543 |

| [3] | Blanco MVF, Ezcurra MD, Bona P, et al. New embryological and palaeontological evidence sheds light on the evolution of the archosauromorph ankle[J]. Scientific Reports, 2020, 10: 5150 |

| [4] | Prothero DR, Foss SE(eds.).The Evolution of Artiodactyls[M]. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2007, 19-31 |

| [5] | Tsubamoto T. Estimating body mass from the astragalus in mammals[J]. Acta Palaeontologica Polonica, 2014, 59(2): 259-265 |

| [6] | Gruwier BJ, Kovarovic K. Ecomorphology of the cervid calcaneus as a proxy for paleoenvironmental reconstruction[J]. Anat Rec (Hoboken), 2022, 305(9): 2207-2226 |

| [7] | Fortin PT, Balazsy JE. Talus Fractures: Evaluation and Treatment[J]. Journal of the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons, 2001, 9(2): 114-127 |

| [8] | Saladié P, Fernández P, Rodríguez-Hidalgo A, et al. The TD 6.3 faunal assemblage of the Gran Dolina site (Atapuerca, Spain): A late Early Pleistocene hyena den[J]. Historical Biology, 2017, 29(7): 1-19 |

| [9] | Orbach M, Yeshurun R. The hunters or the hunters: Human and hyena prey choice divergence in the Late Pleistocene Levant[J]. Journal of Human Evolution, 2021, 160: 102572 |

| [10] | Lyman RL. Vertebrate Taphonomy[M]. London: Cambridge University Press, 1994, 70-113 |

| [11] | Haruda AF. Separating Sheep (Ovis aries L.) and Goats (Capra hircus L.) Using Geometric Morphometric Methods: An Investigation of Astragalus Morphology from Late and Final Bronze Age Central Asian Contexts[J]. Int. J. Osteoarchaeology, 2017, 27: 551-562 |

| [12] | Darney T. Analysis of the talus or astragalus bone of select squirrels for taxonomic diagnosis[D]. MA thesis, State College: The Pennsylvania State University, 2013, 2-12 |

| [13] | Pierre O, Dziomber I, Manuela A, et al. The differentiated impacts and constraints of allometry, phylogeny, and environment on the ruminants' ankle bone[J]. Commun Biol, 2025, 8(456): 1-13 |

| [14] | Sambo R, Hanon R, Maringa N, et al. Ecomorphological analysis of bovid remains from the Plio-Pleistocene hominin-bearing deposit of Unit P at Kromdraai, South Africa[J]. Journal of Archaeological Science: Reports, 2025, 61: 104871 |

| [15] | Hanon R, Fourvel JB, Sambo R, et al. New fossil Bovidae (Mammalia: Artiodactyla) from Kromdraai Unit P, South Africa and their implication for biochronology and hominin palaeoecology[J]. Quaternary Science Reviews, 2024, 331: 108621 |

| [16] | Wendy DB, Nicolás EC, Benjamin PK. Climbing adaptations, locomotory disparity and ecological convergence in ancient stem ‘kangaroos'[J]. R. Soc. Open Sci, 2019, 6: 181617 |

| [17] | Tong HW, Zhang B, Chen X, et al. New fossils of small and medium-sized bovids from the Early Pleistocene Site of Shanshenmiaozui in Nihewan Basin, North China[J]. Vertebrata PalAsiatica, 2022, 60(2): 134-168 |

| [18] | 张双权, 张乐, 栗静舒, 等. 晚更新世晚期中国古人类的广谱适应生存——动物考古学的证据[J]. 中国科学:地球科学, 2016, 46(8): 1024-1036 |

| [19] | Wu XJ, Pei SW, Cai YJ, et al. Archaic human remains from Hualongdong, China, and Middle Pleistocene human continuity and variation[J]. PNAS, 2019, 116: 9820-9824 |

| [20] | Wu XJ, Pei SW, Cai YJ, et al. Morphological description and evolutionary significance of 300 ka hominin facial bones from Hualongdong, China[J]. Journal of Human Evolution, 2021, 161: 103052 |

| [21] | Wu XJ, Pei SW, Cai YJ, et al. Morphological and morphometric analyses of a late Middle Pleistocene hominin mandible from Hualongdong, China[J]. Journal of Human Evolution, 2023, 182: 103411 |

| [22] | Xing S, Wu XJ, Liu W, et al. Middle Pleistocene human femoral diaphyses from Hualongdong, Anhui Province, China[J]. American Journal of Physical Anthropology, 2021, 174: 285-298 |

| [23] | 宫希成, 郑龙亭, 邢松, 等. 安徽东至华龙洞出土的人类化石[J]. 人类学学报, 2014, 33(4): 427-436 |

| [24] | 董哲, 战世佳. 安徽东至县华龙洞旧石器时代遗址出土石制品研究[J]. 东南文化, 2015, 6: 63-71 |

| [25] | 董哲, 裴树文, 盛锦朝, 等. 安徽东至华龙洞古人类遗址2014-2016年出土的石制品[J]. 第四纪研究, 2017, 37(4): 778-788 |

| [26] | 同号文, 吴秀杰, 董哲, 等. 安徽东至华龙洞古人类遗址哺乳动物化石的初步研究[J]. 人类学学报, 2018, 37(2): 284-305 |

| [27] | Jiangzuo QG, Werdelin L, Zhang K, et al. Prionailurus kurteni (Felidae, Carnivora), a new species of small felid from the late Middle Pleistocene fossil hominin locality of Hualongdong, southern China[J]. Annales Zoologici Fennici, 2024, 61(1): 35-342 |

| [28] | 裴树文, 蔡演军, 董哲, 等. 安徽东至华龙洞遗址洞穴演化与古人类活动[J]. 人类学学报, 2022, 41(4): 593-607 |

| [29] | 李潇丽, 董哲, 裴树文, 等. 安徽东至华龙洞洞穴发育与古人类生存环境[J]. 海洋地质与第四纪地质, 2017, 37(3): 169-179 |

| [30] | 伊丽莎白·施密德. 动物骨骼图谱[M]. 译者:李天元. 武汉: 中国地质大学出版社, 1992, 84-85 |

| [31] | 西蒙·赫森. 哺乳动物骨骼和牙齿鉴定方法指南[M]. 译者:侯彦峰,马萧林. 北京: 科学出版社, 2012, 87-89 |

| [32] | 安格拉·冯登德里施. 考古遗址出土动物骨骼测量指南[M]. 译者:马萧林,侯彦峰. 北京: 科学出版社, 2007, 111-113 |

| [33] | Fisher JW. Bone surface modifications in zooarchaeology[J]. Journal of Archaeological Method and Theory, 1995, 2(1): 7-68 |

| [34] | Behrensmeyer AK. Taphonomic and ecologic information from bone weathering[J]. Paleobiology, 1978, 4(2): 150-162 |

| [35] | Gifford DP. Taphonomy and paleoecology: A critical review of Taphonomyand Paleoecology Archaeology's sister disciplines[J]. Advances in Archaeological Method and Theory, 1981, 4: 365-438 |

| [36] | 张双权. 河南许昌灵井动物群的埋藏学研究[D]. 博士研究生毕业论文, 北京: 中国科学院古脊椎动物与古人类研究所, 2009, 1-216 |

| [37] | Dominguez-Rodrigo M, de Juana S, Galan AB, et al. A new protocol to differentiate trampling marks from butchery cut marks[J]. Journal of Archaeological Science, 2009, 36(12): 2643-2654 |

| [38] | 张双权. 旧石器遗址动物骨骼表面非人工痕迹研究及其考古学意义[J]. 第四纪研究, 2014, 34(1): 131-140 |

| [39] | Binford LR. Bones: Ancient men and modern myth[M]. New York: Academic Press, 1981, 1-320 |

| [40] | Reitz EJ, Wing ES. Zooarchaeology[M]. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1999, 1-455 |

| [41] | Villa P, Mahieu E. Breakage patterns of human long bones[J]. Journal of Human Evolution, 1991, 21(1): 27-48 |

| [42] | Capaldo SD, Blumenschine RJ. A quantitative diagnosis of notches made by hammer stone percussion and carnivore gnawing in bovid long bones[J]. American Antiquity, 1994, 59(4): 724-748 |

| [43] | Blumenschine RJ, Marean CW, Capaldo SD. Blind tests of interanalyst correspondence and accuracy in the identification of cut marks, percussion marks, and carnivore tooth marks on bone. Marks, percussion marks, and carnivore tooth marks on bone surfaces[J]. Journal of Archaeological Science, 1996, 23(4): 493-507 |

| [44] | Young CC. On the artiodactyla from the Sinanthropus site at Choukoutien[M]. Palaeontologia Sinica, Ser. C, 1932, 8(2): 1-100 |

| [45] | 同号文, 刘金毅, 张双权. 周口店田园洞大中型哺乳动物记述[J]. 人类学学报, 2004, 23(3): 213-221 |

| [46] | Uzunidis A, Rufà A, Blasco R, et al. Speciated mechanism in Quaternary cervids (Cervus and Capreolus) on both sides of the Pyrenees: a multidisciplinary approach[J]. Scientific Reports, 2022, 12(1): 20200 |

| [47] | 黄万波, 朱学稳, 王训一. 记桂林穿山洞发现的鬣羚和大熊猫化石[J]. 古脊椎动物与古人类, 1983, 21(2): 151-159+183-184 |

| [48] | 邹松林, 陈曦, 张贝, 等. 江西萍乡上栗县晚更新世哺乳动物化石发现[J]. 人类学学报, 2016, 35(1): 109-120 |

| [49] | 王晓敏, 许春华, 同号文. 湖北郧西白龙洞古人类遗址的大额牛化石[J]. 人类学学报, 2015, 34(3): 338-352 |

| [50] | Liang QY, Chen QJ, Zhang NF, et al. Subsistence strategies in the Late Neolithic and Bronze Age in Nenjiang River Basin: A zooarchaeological and stable isotope analysis of faunal remains at Honghe site, Northeast China[J]. International Journal of Osteoarchaeology, 2023, 33(2): 271-284 |

| [51] | Saxon EC. The mobile herding economy of Kebarah Cave, Mt Carmel: An economic analysis of the faunal remains[J]. Journal of Archaeological Science, 1974, 1(1): 27-45 |

| [52] | Fujita M, Kawamura Y, Murase N. Middle Pleistocene wild boar remains from NT Cave, Niimi, Okayama Prefecture, west Japan[J]. Journal of Geosciences, Osaka City University, 2000, 43(4): 57-95 |

| [53] | Faure M, Guérin C. Le Sus scrofa (Mammalia, Artiodactyla, Suidae) du gisement Pléistocène Supérieur de Jaurens, a Nespouls, Corrèze, France[J]. Nouvelles Archives du Museum d'Histoire Naturelle de Lyon, fasc. 1983, 21: 45-63 |

| [54] | Filoux A, Suteethorn V. A late Pleistocene skeleton of Rhinoceros unicornis (Mammalia, Rhinocerotidae) from western part of Thailand (Kanchanaburi Province)[J]. Geobios, 2018, 51(1): 31-49 |

| [55] | Guérin C. Les rhinocéros (Mammalia, Perissodactyla) du Miocène terminal au Pléistocène supérieur en Europe occidentale. Comparaison avec les espèces actuelles[M]. Documents des Laboratoires de Géologie de Lyon, 1980, 79: 1-1185 |

| [56] | Beden M, Guérin C. Le gisement de vertébrés du Phnom Loang (province de Kampot, Cambodge): faune pléistocène moyen terminal (Loangien)[J]. Geography, 1973, 27: 1-97 |

| [57] | Tsoukala E, Guérin C. The Rhinocerotidae and Suidae of the middle pleistocene from petralona cave (Macedonia, Greece)[J]. Acta zool. bulg., 2016, 68(2): 243-264 |

| [58] | 周本雄, 刘后一. 青海共和更新世的哺乳动物化石[J]. 古脊椎动物与古人类, 1959, 4: 217-223 |

| [59] | 陈胜前, 罗虎. 安徽东至县华龙洞旧石器时代遗址发掘简报[J]. 考古, 2012, 4: 7-13 |

| [60] | Shipman P, Rose J. Early hominid hunting, butchering, and carcass-processing behaviors: Approaches to the fossil record[J]. Journal of Anthropological Archaeology, 1983, 2(1): 57-98 |

| [61] | Stiner MC, Gopher A, Barkai R. Hearth-side socioeconomics, hunting and paleoecology during the late Lower Paleolithic at Qesem Cave, Israel[J]. Journal of Human Evolution, 2011, 60: 213-233 |

| [62] | 尤悦. 新疆东黑沟遗址出土动物骨骼研究[D]. 博士研究生毕业论文, 北京: 中国社会科学院大学, 2012, 129-168 |

/

| 〈 |

|

〉 |