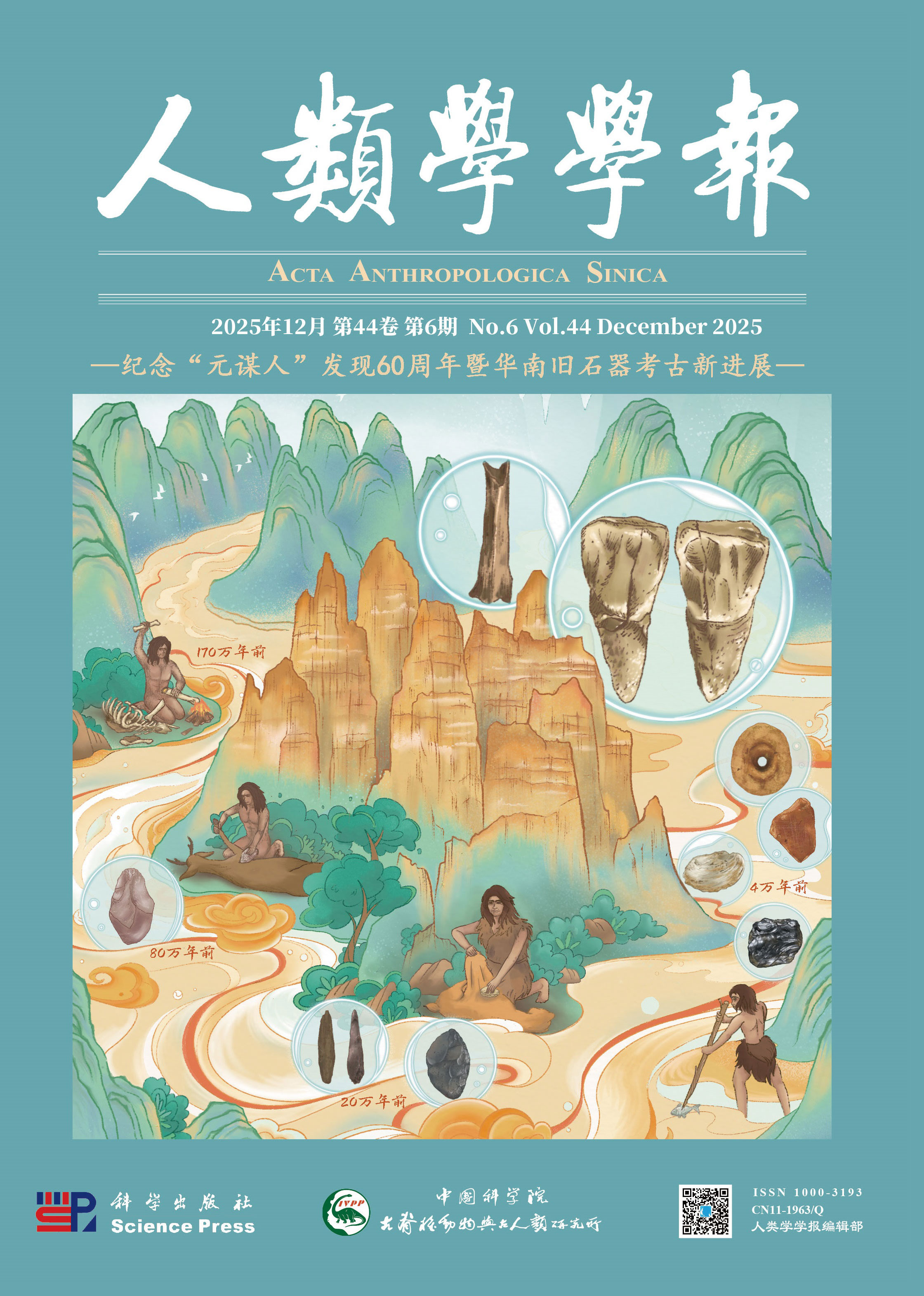

Organized by:Chinese Academy of Sciences

Sponsored by:Institute of Vertebrate Paleontology and Paleoanthropology

Published:China Science Publishing & Media Ltd

Sponsored by:Institute of Vertebrate Paleontology and Paleoanthropology

Published:China Science Publishing & Media Ltd

English Version

English Version