收稿日期: 2019-01-28

修回日期: 2019-06-04

网络出版日期: 2020-09-10

基金资助

山西省“三晋学者支持计划”专项经费;国家自然科学基金面上项目(41672023);国家自然科学基金面上项目(41772025)

A zooarchaeological analysis of the burned bone from the Shizitan Site 9, Shanxi, China

Received date: 2019-01-28

Revised date: 2019-06-04

Online published: 2020-09-10

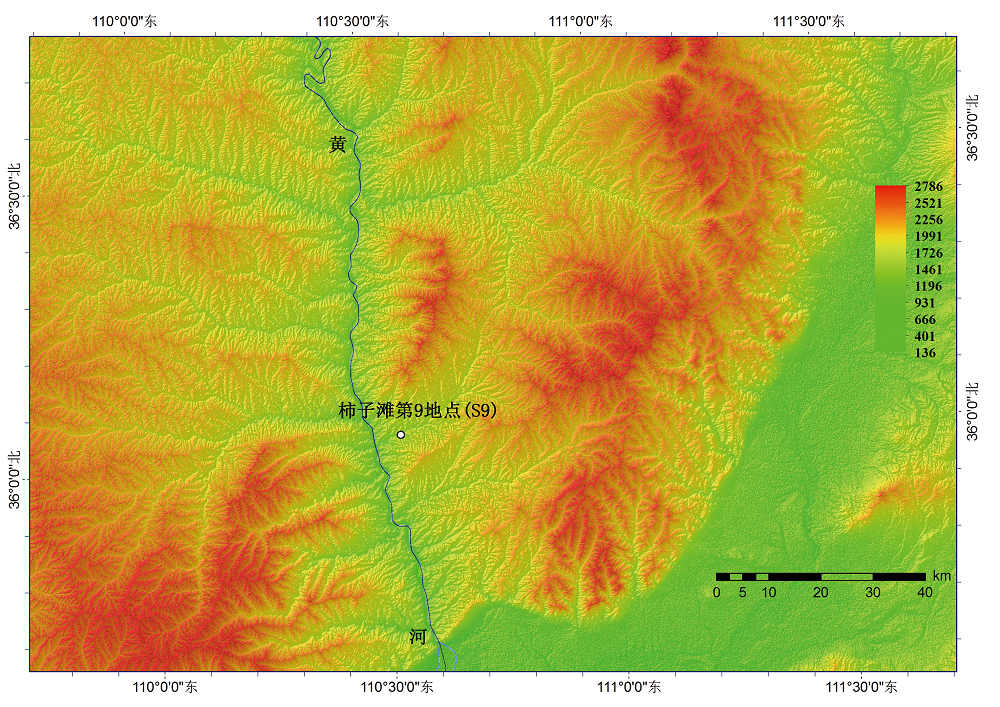

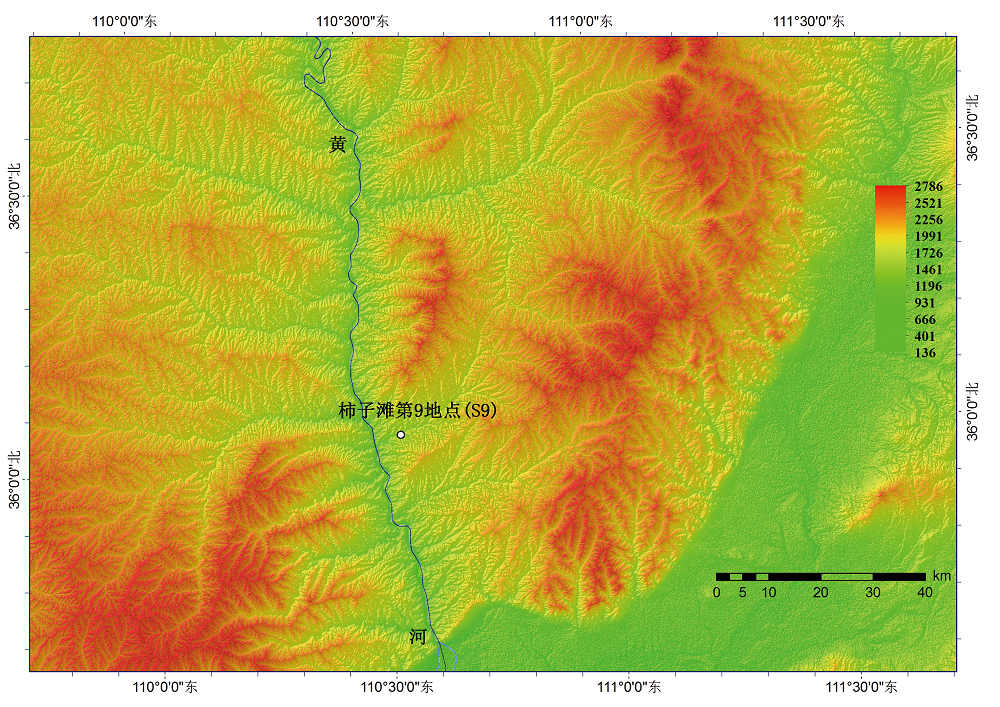

柿子滩遗址第9地点(S9)位于山西省吉县柏山寺乡高楼河村黄河支流的清水河畔,西距黄河约7 km。从2000年发现至今,该遗址前后历经三次发掘,出土大量细石叶制品、动物化石、数件蚌制品、骨针及磨制石器等。本文重点对S9地点第4 层(12,575-11,600 cal. BP)及第5层(13,000 cal. BP)出土的动物遗存,尤其是其中测量尺寸在2cm以下的大量烧骨进行了埋藏学与动物考古学方面的观察和分析。研究结果显示,S9地点的烧骨是古人类烧烤猎物、维护遗址(甚至可能还包括以骨骼作燃料)等生存行为活动的文化残留。此外,S9地点出土烧骨的空间分布分析表明,古人类在上述行为活动之后,可能又将烧灼后的残存骨骼(与灰烬等)清理出火塘并堆放在其核心生活区的周边位置。

张双权 , 宋艳花 , 张乐 , 许乐 , 李磊 , 石金鸣 . 柿子滩遗址第9地点出土的动物烧骨[J]. 人类学学报, 2019 , 38(04) : 598 -612 . DOI: 10.16359/j.cnki.cn11-1963/q.2019.0047

Located at the Gaolouhe village, Jixian County of the Shanxi Province, the Shizitan site(Locality 9) is roughly 7 km to the Yellow River. Discovered in 2000, this site was systematically excavated in 2001, 2002 and 2005. Along with thousands of lithic tools of microblade technology, a dozen of organic artifacts and lithic grinding tools, plenty of faunal remains were recovered from the 3 field seasons of excavation. Based mainly on an observation of the taphonomic features of the faunal remains from Layer 4(12,575-11,600 cal. BP) and Layer 5(ca. 13,000 cal. BP), particularly of the small-sized bone fragments from the site, it could be argued that the burned bones here are most probably a palimpsest of several episodes of human behavior centering around the hearth, including but not limited to roasting meat, burning bones for site maintenance and as a supplementary source of fuel. Besides, it seems clear that humans at the site moved the fire residues out of the fireplace and later on dumped them at its peripheries.

Key words: Shizitan site; Burned bones; Taphonomy; Zooarchaeology; Paleolithic

| [1] | Lyman RL. Vertebrate Taphonomy[M]. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1994: 1-552 |

| [2] | Gifford-Gonzalez DP. Ethnographic analogues for interpreting modified bones: some cases from East African[A]. In: Bonnichsen R, Sorg MH, eds. Bone Modification[C]. Orono: University of Maine Center for the Study of the First Americans, 1989, 179-246 |

| [3] | Gifford DP. Taphonomy and paleoecology: A critical review of archaeology’s sister disciplines[A]. In: Schiffer MB, ed. Advances in Archaeological Method and Theory[C]. New York and London: Academic Press, 1981, 365-438 |

| [4] | White TD, White T. Prehistoric Cannibalism at Mancos 5MTUMR-2346[M]. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1992 |

| [5] | Correia PM. Fire modification of bone: A review of the literature[A]. In: Haglund WD, Sorg MH, eds. Forensic taphonomy: the postmortem fate of human remains[C]. New York: CRC Press, 1997, 275-293 |

| [6] | Wrangham R. Control of fire in the Paleolithic: Evaluating the cooking hypojournal[J]. Current Anthropology, 2017,58(S16):S303-S313 |

| [7] | Barkai R, Rosell J, Blasco R, et al. Fire for a reason: barbecue at Middle Pleistocene Qesem Cave, Israel[J]. Current Anthropology, 2017,58(S16):S314-S328 |

| [8] | Yravedra J, Uzquiano P. Burnt bone assemblages from El Esquilleu cave(Cantabria, Northern Spain): Deliberate use for fuel or systematic disposal of organic waste?[J]. Quaternary Science Reviews, 2013,68:175-190 |

| [9] | Costamagno S, Théry-Parisot I, Brugal J-P, et al. Taphonomic consequences of the use of bones as fuel. Experimental data and archaeological applications. Paper presented at: Biosphere to Lithosphere, Proceedings of the 9th Conference of the International Council of Archaeozoology. Oxbow books, Oxford, 2005 |

| [10] | Villa P, Bon F, Castel J. Fuel, fire and fireplaces in the Palaeolithic of Western Europe[J]. The Review of Archaeology, 2002,23(1):33-42 |

| [11] | Brain CK. The occurrence of burnt bones at Swartkrans and their implications for the control of fire by early hominids[A]. In: Brain CK, ed. Swartkrans: A Cave’s Chronicle of Early Man[C]. Pretoria: Transvaal Museum, 1993, 229-242 |

| [12] | Shipman P, Foster G, Schoeninger M. Burnt bones and teeth: an experimental study of color, morphology, crystal structure and shrinkage[J]. Journal of Archaeological Science, 1984,11(4):307-325 |

| [13] | Stiner MC, Kuhn SL, Weiner S, et al. Differential Burning, Recrystallization, and Fragmentation of Archaeological Bone[J]. Journal of Archaeological Science, 1995,22(2):223-237 |

| [14] | David B. How was this bone burnt[A]. In: Davidson I, Watson D, eds. Problem Solving in Taphonomy: Archaeological and Paleontological Studies from Europe, Africa and Oceania.[C]. Queensland: Anthropology Museum, University of Queensland, 1990, 65-79 |

| [15] | Nicholson RA. A morphological investigation of burnt animal bone and an evaluation of its utility in archaeology[J]. Journal of Archaeological Science, 1993,20(4):411-428 |

| [16] | Hanson M, Cain. CR. Examining histology to identify burned bone[J]. Journal of Archaeological Science, 2007,34(11):1902-1913 |

| [17] | Shahack-Gross R, Bar-Yosef O, Weiner S. Black-Coloured Bones in Hayonim Cave, Israel: Differentiating Between Burning and Oxide Staining[J]. Journal of Archaeological Science, 1997, 24(5): 439-446 |

| [18] | Oakley KP. On man’s use of fire, with comments on tool-making and hunting[A]. In: Washburn SL, ed. Social life of early man[C]. Chicago: Aldine, 1961, 176-193 |

| [19] | Cole SC, Atwater BF, McCutcheon PT, et al. Earthquake‐induced burial of archaeological sites along the southern Washington coast about AD 1700[J]. Geoarchaeology, 1996,11(2):165-177 |

| [20] | Bennett JL. Thermal alteration of buried bone[J]. Journal of Archaeological Science, 1999,26(1):1-8 |

| [21] | Subías SM. Cooking in zooarchaeology: is this issue still raw[A]. In: Miracle P, Milner N, eds. Consuming Passions and Patterns of Consumption, [C]. Cambridge: McDonald Institute for Archaeological Research, 2002, 7-15 |

| [22] | Villa P, Castel J-C, Beauval C, et al. Human and carnivore sites in the European Middle and Upper Paleolithic: similarities and differences in bone modification and fragmentation[J]. Revue de paléobiologie, 2004,23(2):705-730 |

| [23] | Stiner MC, Kuhn SL, Surovell TA, et al. Bone preservation in Hayonim Cave(Israel): A macroscopic and mineralogical study[J]. Journal of Archaeological Science, 2001,28(6):643-659 |

| [24] | Théry-Parisot I, Costamagno S, Brugal J-P, et al. The use of bone as fuel during the Palaeolithic, experimental study of bone combustible properties[A]. In: Mulville J, Outram AK, eds. The zooarchaeology of fats, oils, milk and dairying: Oxbow Books, 2005 |

| [25] | 石金鸣, 宋艳花. 山西吉县柿子滩遗址第九地点发掘简报[J]. 考古, 2010(10):7-17 |

| [26] | 李晓蓉. 柿子滩旧石器遗址发现的骨针及相关问题研究[D].硕士学位论文, 太原: 山西大学, 2013 |

| [27] | Shizitan Archaeological Team, Shanxi Provincial Institute of Archaeology. Late Paleolithic site at Locality S9 of Shizitan Complex in Jixian County, Shanxi[J]. Archaeology, 2010,12(10):61-69 |

| [28] | Brain CK. The Hunters or the Hunted? An Introduction to African Cave Taphonomy[M]: University of Chicago Press, 1981: 1~384 |

| [29] | Domínguez-Rodrigo M, Barba R, Egeland CP. Deconstructing Olduvai: A Taphonomic Study of the Bed I Sites[M]. New York: Springer, 2007: 1~ 360 |

| [30] | Binford LR. Nunamiut Ethnoarchaeology[M]. New York: Academic Press, 1978: 1-509 |

| [31] | Fisher JW. Bone surface modifications in zooarchaeology[J]. Journal of Archaeological Method and Theory, 1995,2(1):7-68 |

| [32] | Binford LR. Bones: Ancient Men and Modern Myth[M]. New York: Academic Press, 1981: 1~ 320 |

| [33] | Norton CJ, 张双权, 张乐, 等. 上/更新世动物群中人类与食肉动物“印记”的识别[J]. 人类学学报, 2007: 183-192 |

| [34] | 张双权. 旧石器遗址动物骨骼表面非人工痕迹研究及其考古学意义[J]. 第四纪研究, 2014,34:131-140 |

| [35] | Fernandez-Jalvo Y, Andrews P. Atlas of taphonomic identifications: 1001+ images of fossil and recent mammal bone modification[M]. Netherlands: Springer, 2016 |

| [36] | Bosch MD, Nigst PR, Fladerer FA, et al. Humans, bones and fire: Zooarchaeological, taphonomic, and spatial analyses of a Gravettian mammoth bone accumulation at Grub-Kranawetberg(Austria)[J]. Quaternary International, 2012,252:109-121 |

| [37] | Buikstra JE, Swegle M. Bone modification due to burning: experimental evidence[A]. In: Bonnichsen R, Sorg MH, eds. Bone modification[C]. Maine: Centre for the Study of the First Americans, Institute for Quaternary Studies, University of Maine, 1989, 247-258 |

| [38] | Nilssen PJ. An actualistic butchery study in South Africa and its implications for reconstructing hominid strategies of carcass acquisition and butchery in the Upper Pleistocene and Plio-Pleistocene[D]. Ph.D Dissertation. Cape Town: University of Cape Town, 2000 |

| [39] | 吕遵谔, 黄蕴平. 大型肉食哺乳动物啃咬骨骼和敲骨取髓破碎骨片的特征[A].见: 北京大学考古系编. 纪念北京大学考古专业三十周年论文集[C]. 北京: 文物出版社, 1990. 4-39 |

| [40] | Bellomo RV. Methods of determining early hominid behavioral activities associated with the controlled use of fire at FxJj 20 Main, Koobi Fora, Kenva[J]. Journal Of Human Evolution, 1994,27(1-3):173-195 |

| [41] | Bellomo RV. A methodological approach for identifying archaeological evidence of fire resulting from human activities[J]. Journal of Archaeological Science, 1993,20(5):525-553 |

| [42] | Gowlett J, Brink J, Caris A, et al. Evidence of burning from bushfires in southern and east Africa and its relevance to hominin evolution[J]. Current Anthropology, 2017,58(S16):S206-S216 |

| [43] | Petrie CC. Tom Petrie’s reminiscences of early Queensland(dating from 1837)[M]. Watson: Ferguson & Co., 1904 |

| [44] | Walters I. Fire and bones: patterns of discard[A]. In: Meehan B, Jones R, eds. Archaeology with ethnography: an Australian perspective[C]. Canberra: Australian National University, 1988, 215-221 |

| [45] | Jones R. Different strokes for different folks: sites, scale and strategy[A]. In: Johnson I, ed. Holier than Thou: Proceedings of the 1978 Kioloa Conference on Australian Prehistory. [C]. Canberra: Department of Prehistory, Research School of Pacific Studies, Australian National University, 1980, 151-171 |

| [46] | Aldeias V. Experimental approaches to archaeological fire features and their behavioral relevance[J]. Current Anthropology, 2017,58(S16):S191-S205 |

| [47] | Lampert R. The Great Kartran Mystery[M]. Canberra: Department of Prehistory, Research School of Pacific Studies, Australian National University, 1981 |

| [48] | Archer M. Faunal remains from the excavation at Puntutjarpa Rockshelter[J]. Anthropological Papers of the American Museum of Natural History, 1977,54:158-165 |

| [49] | De Graaff G. Gross effects of a primitive hearth on bones[J]. The South African Archaeological Bulletin, 1961: 25-26 |

| [50] | Brit A. Intentional or incidental thermal modification? Analysing site occupation via burned bone[J]. Journal of Archaeological Science, 2009,36(2):528-536 |

| [51] | Zhang S, d’Errico F, Backwell LR, et al. Ma’anshan cave and the origin of bone tool technology in China[J]. Journal of Archaeological Science, 2016,65:57-69 |

| [52] | Speth JD, Meignen L, Bar-Yosef O, et al. Spatial organization of Middle Paleolithic occupation X in Kebara Cave(Israel): Concentrations of animal bones[J]. Quaternary International, 2012,247:85-102 |

| [53] | Oliver J. Carcass Processing by the Hadza: Bone Breakage from Butchery to Consumption. In(Hudson, J., ed.) From Bones to Behavior. Ethnoarchaeological and Experimental Contributions to the Interpretation of Faunal Remains. Illinois: Center for Archaeological Investigations. Southern Illinois University at Carbondale[J]. Occasional Paper, 1993,31:200-227 |

| [54] | Fladerer F, Salcher-Jedrasiak T, Neugebauer-Maresch C, et al. Housing area and periphery within Gravettian mammoth hunters camps at Krems, Lower Austria e the zooarchaeological and taphonomic view[J]. Quaternaire, Hors-série, 2010,3:132-134 |

| [55] | Speth JD. Housekeeping, Neandertal-style: hearth placement and midden formation in Kebara cave(Israel)[A]. In: Hovers E, Kuhn SL, eds. Transitions Before the Transition: evolution and stability in the Middle Paleolithic and Middle Stone Age[C]. New York: Springer, 2006, 171-188 |

| [56] | Solari A, Olivera D, Gordillo I, et al. Cooked bones? Method and practice for identifying bones treated at low temperature[J]. International journal of osteoarchaeology, 2015,25(4):426-440 |

| [57] | Alhaique F. Do patterns of bone breakage differ between cooked and uncooked bones? An experimental approach[J]. Anthropozoologica, 1997,25(26):49-56 |

| [58] | Speth J, Clark J. Hunting and overhunting in the Levantine late Middle Palaeolithic[J]. Before Farming, 2006,2006(3):1-42 |

| [59] | Carmody RN, Weintraub GS, Wrangham RW. Energetic consequences of thermal and nonthermal food processing[J]. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 2011,108(48):19199-19203 |

| [60] | Carmody RN, Wrangham RW. The energetic significance of cooking[J]. Journal Of Human Evolution, 2009,57(4):379-391 |

| [61] | Costamagno S, Théry-Parisot I, Castel J-C, et al. Combustible ou non? analyse multifactorielle et modèles explicatifs sur les ossements br?lés paléolithiques[A]. In: Théry-Parisot I, Costamagno S, Henry A, eds. Gestion des combustibles au Paléolithique et au Mésolithique: nouveaux outils, nouvelles interprétations[C]. Oxford: Archaeopress, 2009, 69-84 |

| [62] | Morin E. Taphonomic implications of the use of bone as fuel[J]. The taphonomy of burned organic residues and combustion features in archaeological contexts, 2010,2:209-217 |

| [63] | Théry-Parisot I. Fuel management(bone and wood) during the Lower Aurignacian in the Pataud rock shelter(Lower Palaeolithic, Les Eyzies de Tayac, Dordogne, France). Contribution of experimentation[J]. Journal of Archaeological Science, 2002,29(12):1415-1421 |

| [64] | Soffer O, Adovasio JM, Kornietz NL, et al. Cultural stratigraphy at Mezhirich, an Upper Palaeolithic site in Ukraine with multiple occupations[J]. Antiquity, 1997,71(271):48-62 |

| [65] | Uzquiano P, Yravedra J, Zapata BR, et al. Human behaviour and adaptations to MIS 3 environmental trends(> 53-30 ka BP) at Esquilleu cave(Cantabria, northern Spain)[J]. Quaternary International, 2012,252:82-89 |

| [66] | Marquer L, Otto T, Nespoulet R, et al. A new approach to study the fuel used in hearths by hunter-gatherers at the Upper Palaeolithic site of Abri Pataud(Dordogne, France)[J]. Journal of Archaeological Science, 2010,37(11):2735-2746 |

| [67] | Marquer L. From microcharcoal to macrocharcoal: reconstruction of the “wood charcoal” signature in Paleolithic archaeological contexts[A]. In: Théry-Parisot I, Chabal L, Costamagno S, eds. The taphonomy of burned organic residues and combustion features in archaeological contexts(proceedings of the round table, Valbonne, May 27-29 2008, CEPAM)[C]. Toulouse: P@lethnologie Association, 2010, 105-115 |

| [68] | Dibble HL, Berna F, Goldberg P, et al. A preliminary report on Pech de l’Azé IV, layer 8(Middle Paleolithic, France)[J]. PaleoAnthropology, 2009,2009:182-219 |

| [69] | Blasco R, Rosell J, Smith KT, et al. Tortoises as a dietary supplement: A view from the Middle Pleistocene site of Qesem Cave, Israel[J]. Quaternary Science Reviews, 2016,133:165-182 |

| [70] | Schiegl S, Goldberg P, Pfretzschner HU, et al. Paleolithic burnt bone horizons from the Swabian Jura: Distinguishing between in situ fireplaces and dumping areas[J]. Geoarchaeology-an International Journal, 2003,18(5):541-565 |

| [71] | Miller CE, Conard NJ, Goldberg P, et al. Dumping, sweeping and trampling: experimental micromorphological analysis of anthropogenically modified combustion features[J]. Palethnologie, 2010,2:25-37 |

/

| 〈 |

|

〉 |