河南郑州汪沟遗址出土的植硅体

收稿日期: 2019-12-26

修回日期: 2021-05-09

网络出版日期: 2022-06-16

基金资助

国家自然基金“基于环境与农业的鲁北地区龙山文化人地关系研究”(41771230);本项目系郑州中华之源与嵩山文明研究会资助课题(Y2020-3)

Phytolith from the Wanggou site in Zhengzhou, Henan

Received date: 2019-12-26

Revised date: 2021-05-09

Online published: 2022-06-16

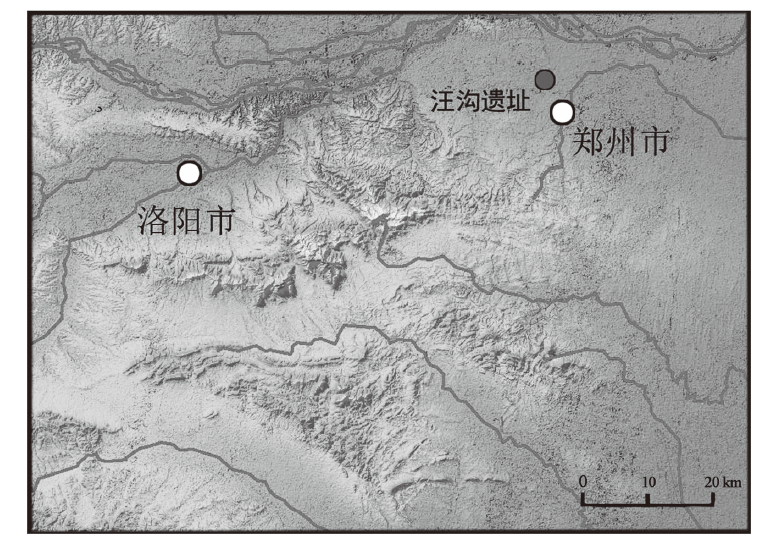

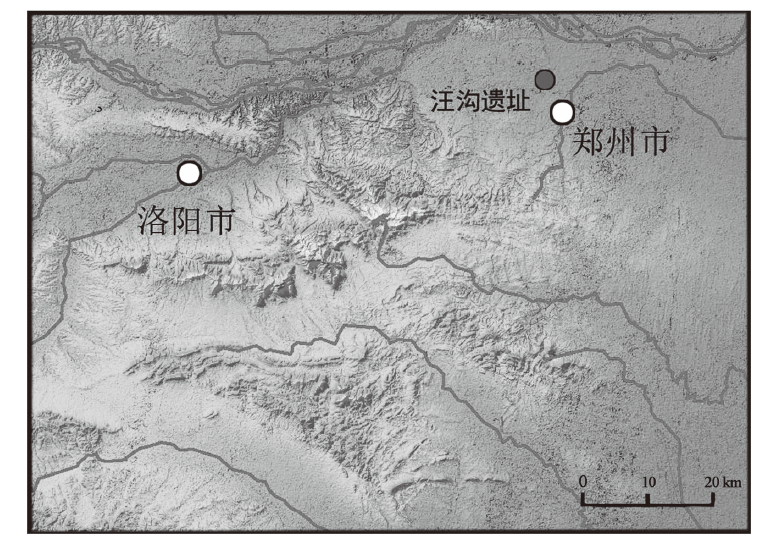

汪沟遗址是豫中地区仰韶文化晚期一处高等级的中心性聚落遗址。在2014-2016年三个季度的发掘中我们系统采集了植硅体土样并进行了分析。研究结果显示:汪沟聚落仰韶文化晚期的农作物有粟、黍和水稻;黍粟比例较高,水稻的比例较低;稻作农业较旱作农业规模小,种植少,但水稻和粟黍的出土概率相差很小,说明水稻和粟黍一样都是汪沟先民日常食用的作物,是汪沟先民植物性食物的重要组成部分。我们根据炭化植物遗存分析的结果推测,汪沟遗址的粟黍和水稻在不同的季节以连杆带穗的方式收割,然后在壕沟南部区域对谷物进行集中脱粒,脱粒后的粟黍和稻被共同储藏在房址周围,个体家庭需要食用的时候在房屋内或周围进行脱壳。大规模的谷物收割和在特定场所集中进行的脱粒加工活动说明,汪沟聚落有着较强的劳动组织能力,有较大型社会生产组织的存在,大家庭或家族公社是聚落生产与生活中的基本组成单位。

杨凡 , 顾万发 , 段绮梦 , 郑晓蕖 , 贾茵 , 靳桂云 . 河南郑州汪沟遗址出土的植硅体[J]. 人类学学报, 2022 , 41(03) : 429 -438 . DOI: 10.16359/j.1000-3193/AAS.2021.0065

The Wanggou site is a high-level central settlement site in the late Yangshao culture in the middle of Henan Province. Between 2014 and 2016, we systematically collected phytolith soil samples, and found that foxtail millet, broomcorn millet, rice, and soybean make up the crop group of the settlement. The proportion of the millet is high, rice is low, and rice farming is smaller than that of dry farming. Rice and millet both are daily crops of Wanggou ancestors. Combining the analysis of phytoliths and carbonized plant remains, we speculate that the millet and rice of the Wanggou site are harvested in the different seasons by means of connecting rods with spikes, and then the grains are threshed in the southern part of the trench by collective activities. After threshing, millet and rice are stored together around the house and then distributed to individual families, which are shelled in or around the house when they need to eat. Large-scale grain harvesting and concentrated threshing processing activities in specific places show that the Wanggou settlement has strong labor organization ability, reflecting the existence of larger social production organizations, and large families or family communes become the basic unit of production and life.

Key words: The late Yangshao culture; phytolith; agriculture; social organization

| [1] | 严文明. 中国史前文化的统一性与多样性[J]. 文物, 1987(3): 38-50 |

| [2] | 赵辉. 以中原为中心的历史趋势的形成[J]. 文物, 2000(1): 41-47 |

| [3] | 韩建业. 庙底沟时代与“早期中国”[J]. 考古, 2012(2): 59-69 |

| [4] | 戴向明. 中原地区早期复杂社会的形成与初步发展[A].见:北京大学考古文博学院,北京大学中国考古学研究中心(编).考古学研究(九)[C]. 北京: 文物出版社, 2012: 481-527 |

| [5] | 韩建业. 中原和江汉地区文明化进程比较[J]. 江汉考古, 2016(6): 39-44 |

| [6] | 庞小霞, 高江涛. 中原地区文明化进程中农业经济考察[J]. 农业考古, 2006(4): 1-13+26 |

| [7] | 袁靖. 中华文明探源工程十年回顾:中华文明起源与早期发展过程中的技术与生业研究[J]. 南方文物, 2012(4): 5-12 |

| [8] | 钟华. 中原地区仰韶中期到龙山时期植物考古学研究[D]. 北京: 中国社会科学院, 2016: 77 |

| [9] | 钟华, 杨亚长, 邵晶, 等. 陕西省蓝田县新街遗址炭化植物遗存研究[J]. 南方文物, 2015(3): 36-43 |

| [10] | 刘晓媛. 案板遗址2012年发掘植物遗存研究[D]. 西安: 西北大学, 2014 |

| [11] | 陈星灿, 刘莉, 李润权, 等. 中国文明腹地的社会复杂化进程——伊洛河地区的聚落形态研究[J]. 考古学报, 2003(2): 161-218 |

| [12] | 王灿. 中原地区早期农业——人类活动及其与气候变化关系研究[D]. 北京: 中国科学院, 2016: 105-110 |

| [13] | 秦岭. 中国农业起源的植物考古研究与展望[A].见:北京大学考古文博学院,北京大学中国考古学研究中心(编).考古学研究(九)[C]. 北京: 文物出版社, 2012: 260-315 |

| [14] | 刘莉, Levin MJ, 陈星灿, 等. 河南偃师灰嘴遗址新石器时代和二里头文化时期工具残留物及微痕分析[J]. 中原文物, 2018, 6: 82-97 |

| [15] | 孙亚男. 郑州地区仰韶至青铜时代先民植物资源利用与陶器功能的淀粉粒分析[D]. 合肥: 中国科学技术大学, 2018: 18-25 |

| [16] | 赵志军. 植物考古学:理论、方法和实践[M]. 北京: 科学出版社, 2010: 38 |

| [17] | 王永吉, 吕厚远. 植物硅酸体研究及应用[M]. 北京: 海洋出版社, 1992 |

| [18] | 李泉, 吕厚远, 王伟铭. 国际植硅体命名法规 (International Code for Phytolith Nomenclature 1.0 )的介绍与讨论[J]. 古生物学报, 2009(1): 134-141 |

| [19] | Pearsall DM, Piperno DR, Dinan EH, et al. Distinguishing rice (Oryza sativa Poaceae) from wild Oryza species through phytolith analysis: results of preliminary research[J]. Economic Botany, 1995, 49(2): 183-196 |

| [20] | Zhao ZJ, Pearsall DM, Benfer RA, et al. Distinguishing rice (Oryza sativa poaceae) from wild Oryza species throuth phytolith analysis, II Finalized method[J]. Economic Botany, 1998, 52(2): 134-145 |

| [21] | Gu YS, Zhao ZJ, Pearsall DM. Phytolith morphology research on wild and domesticated rice species in East Asia[J]. Quaternary International, 2013, 287: 141-148 |

| [22] | Lu HY, Zhang JP, Wu NQ, et al. Phytolith analysis for the discrimination of Foxtail millet (Setaria italica) and Common millet (Panicum miliaceum)[J]. PLOS ONE, 2009, 4(2): e4448 |

| [23] | 王永吉, 吕厚远. 植物硅酸体研究及应用[M]. 北京: 海洋出版社, 1992: 164-181 |

| [24] | 杨凡, 顾万发, 靳桂云. 河南郑州汪沟遗址炭化植物遗存分析[J]. 中国农史, 2020, 39(2): 3-12+35 |

| [25] | 西安市文物保护考古研究院. 西安鱼化寨[M]. 北京: 科学出版社, 2017: 1313-1326 |

| [26] | 赵志军. 中国古代农业的形成过程——浮选出土植物遗存证据[J]. 第四纪研究, 2014, 34(1): 73-84 |

| [27] | 张建平, 吕厚远, 吴乃琴, 等. 关中盆地6000-2100 cal.a B.P. 期间黍、粟农业的植硅体证据[J]. 第四纪研究, 2010, 30(2): 287-297 |

| [28] | 李晶静, 张勇, 张永兵. 新疆吐鲁番胜金店墓地小麦遗存加工处理方式初探[J]. 第四纪研究, 2015, 35(1): 218-228 |

| [29] | 王清刚. 2012年度上海广富林遗址山东大学发掘区发掘报告[D]. 济南: 山东大学, 2014: 65-67 |

| [30] | 中美联合考古队. 两城镇——1998-2001年发掘报告[M]. 北京: 文物出版社, 2017: 1124-1153 |

| [31] | 靳桂云, 方燕明, 王春燕. 河南登封王城岗遗址土壤样品的植硅体分析[J]. 中原文物, 2007(2): 93-100 |

| [32] | Reddy SN. If the threshing floor could talk: integration of agriculture and pastrolism during the Late Harappan in Gujurat, India[J]. Journal of Anthropological Archaeology, 1997, 16(2): 162-187 |

| [33] | Fuller DQ, Stevens C. Agriculture and the development of complex societies: an archaeobotanial agenda[J]. In: Faribairn AS (Eds.). From foragers to farmers papers in honour of Gordon C[M]. Oxford: Oxbow Books Limited, 2009: 37-57 |

| [34] | Fuller DQ, Stevens C, McClatchie M. Routine activities, tertiary refuse and labor organization: social inferences from everyday archaeobotany[J]. In: Madella M, Lancelotti C, Savard M(Eds.). Ancient Plants and People Contemporary Trends in Archaeobotany[M]. Tucson: University of Arizona Press, 2014: 174-217 |

| [35] | 宋吉香, 赵吉军, 傅稻镰. 不成熟粟、 黍的植物考古学意义——粟的作物加工实验[J]. 南方文物, 2014(3): 60-71 |

| [36] | Harvey EL, Fuller DQ. Investigating crop processing using phytolith: the example of rice and millets[J]. Journal of Archaeological Science, 2005, 32(5): 739-752 |

| [37] | Stevens CJ. An Investigation of Agricultural Consumption and Production Models for Prehistoric and Roman Britain[J]. Environmental Archaeology, 2003, 8(1): 61-76 |

| [38] | Weisskopf A. Millets, rice and farmers: phytoliths as indicators of agricultural, social and ecological change in Neolithic and Bronze Age Central China[J]. BAR International Series 2589. Oxford: Archaeopress, 2014 |

| [39] | Weisskopf A, Deng ZH, Qin L, et al. The interplay of millets and rice in Neolithic central China: Integrating phytoliths into the archaeobotany of Baligang[J]. Archaeological Research in Asia, 2015(4): 36-45 |

| [40] | 北京大学考古文博学院, 河南省文物考古研究所. 登封王城岗考古发现与研究(2002- 2005)[M]. 郑州: 大象出版社, 2008, 933-938 |

| [41] | 蒋宇超. 中国北方地区龙山时代的农业与社会[D]. 北京: 北京大学, 2016 |

| [42] | Song JX, Wang LZ, Fuller DQ. A regional case in the development of agriculture and crop processing in northern China from the Neolithic to Bronze Age: archaeobotanical evidence from the Sushui River survey, Shanxi province[J]. Archaeological & Anthropological Sciences. 2019, 11(2): 667-682 |

| [43] | 王灿, 吕厚远, 顾万发, 等. 全新世中期郑州地区古代农业的时空演变及其影响因素[J]. 第四纪研究, 2019, 39(1): 108-122 |

/

| 〈 |

|

〉 |