浅议古人类活动遗址的动物埋藏学研究方法

收稿日期: 2021-01-19

修回日期: 2021-02-18

网络出版日期: 2022-06-16

基金资助

科技部国家重点研发计划(2020YFC1521500);中国科学院战略性先导科技专项(B类)(XDB26000000)

A brief discussion on the approaches of taphonomic study of archaeofaunas from paleoanthropological sites

Received date: 2021-01-19

Revised date: 2021-02-18

Online published: 2022-06-16

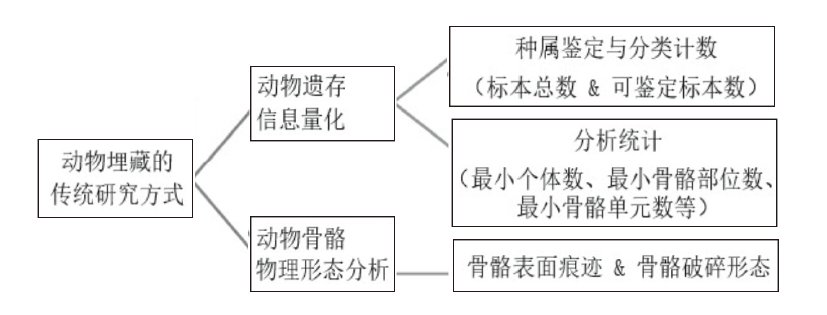

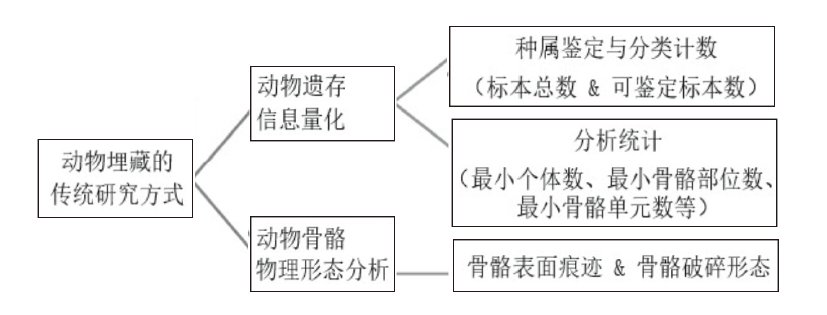

随着学科的发展,有关古人类活动遗址的研究手段逐渐多样化,学者们从不同研究视角分别揭示了早期人类对遗址的利用行为。近年来,作为古人类行为研究的重要分支,动物埋藏研究在阐释遗址形成过程及其背后的影响因素方面起到了重要作用。本文简要梳理了对保存有动物遗存的古人类活动遗址进行动物埋藏研究的主要方法和思路,同时,文章介绍了部分动物埋藏的典型模型与经典案例,以此对动物埋藏研究中存在的缺陷与可能的解决方式进行探讨。此外,作者对动物埋藏研究的方法演进进行了简单回顾,为解决遗址中出现的多个埋藏因素相互影响而导致的混乱及重叠现象提供了可供参考的研究思路;在此基础上,结合中国古人类活动遗址的相关研究进展,本文也对中国考古遗址相关研究的思路和方向提出了建议。

杜雨薇 , 丁馨 , 裴树文 . 浅议古人类活动遗址的动物埋藏学研究方法[J]. 人类学学报, 2022 , 41(03) : 523 -534 . DOI: 10.16359/j.1000-3193/AAS.2021.0020

With the development of the research discipline, diversified research approaches to early human occupation reveal different occupation strategies adopted by early humans from the use of paleoanthropological sites. In recent years, as an important branch of exploring ancient human behavior, animal taphonomy plays an important role in explaining the formation processes of sites and even the influencing factors behind the site formation. This paper reviews the main approaches to taphonomic investigation of animal assemblages from paleoanthropological sites. In addition, this paper also introduces some typical models and classic research cases in order to analyze the defects and possible solutions in studying animal bone formation processes from sites. Furthermore, fundamental research methods of animal taphonomy, which are systematically reviewed by the authors, provide feasible research scopes of the taphonomic results from multiple phenomena obtained from archaeological site formation. Finally, combined with the related studies of some paleoanthropological sites in China, a discussion on the potential reference for research methods and approaches in Chinese animal taphonomy studies is also presented in the current paper.

| [1] | Lyman RL. Vertebrate Taphonomy[M]. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1994 |

| [2] | Andrews P. Experiments in Taphonomy[J]. Journal of Archaeological Science, 1995, 22(2): 147-153 |

| [3] | Brain CK. The Hunters or the Hunted?: An Introduction to African Cave Taphonomy[M]. Chicago and London: University of Chicago Press, 1981 |

| [4] | Binford LR. Bones: Ancient Men and Modern Myths[M]. New York: Academic Press, 1981 |

| [5] | Lyman RL. Zooarchaeology and taphonomy: a general consideration[J]. Journal of Ethnobiology, 1987, 7(1): 93-117 |

| [6] | Russell N. Social Zooarchaeology: Humans and Animals in Prehistory[M]. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2011 |

| [7] | Enloe JG. Middle Palaeolithic cave taphonomy: discerning humans from hyenas at Arcy-sur-Cure, France[J]. International Journal of Osteoarchaeology. 2012, 22(5): 591-602 |

| [8] | Meier JS, Yeshurun R. Contextual taphonomy for zooarchaeology: Theory, practice and select Levantine case studies[J]. Journal of Archaeological Science: Reports. 2020, 34: 1-8 |

| [9] | Domínguez-Rodrigo M. Meat-eating by early hominids at the FLK 22 Zinjanthropus site, Olduvai Gorge (Tanzania): an experimental approach using cut-mark data[J]. Journal of Human Evolution. 1997, 33(6): 669-690 |

| [10] | O’Connor TP. The archaeology of animal bones[M]. Stroud: Sutton, 2000 |

| [11] | Yravedra J, Domínguez-Rodrigo M. The shaft-based methodological approach to the quantification of long limb bones and its relevance to understanding hominid subsistence in the Pleistocene: application to four Paleolithic sites[J]. Journal of Quaternary Science, 2008, 24(1): 85-96 |

| [12] | Norton CJ, 张双权, 张乐, 等. 上/更新世动物群中人类与食肉动物“印记”的识别[J]. 人类学学报, 2007, 26(2): 183-192 |

| [13] | 张乐, 王春雪, 张双权, 等. 马鞍山遗址动物群的死亡年龄研究[J]. 人类学学报, 2009, 28(3): 306-318 |

| [14] | 张双权, 高星, 陈福友, 等. 周口店第一地点西剖面2009-2010年发掘报告[J]. 人类学学报, 2016, 35(1): 63-75 |

| [15] | Norton CJ, Gao X. Hominine-carnivore interactions during the Chinese Early Paleolithic: Taphonomic perspectives from Xujiayao[J]. Journal of Human Evolution, 2008, 55(1): 164-178 |

| [16] | 张双权, 高星, 张乐, 等. 灵井动物群的埋藏学分析及中国北方旧石器时代中期狩猎--屠宰遗址的首次记录[J]. 科学通报, 2011, 35: 2988-2995 |

| [17] | Domínguez-Rodrigo M, Egeland CP, Barba R. The “physical attribute” taphonomic approach[A]. In: Domínguez-Rodrigo M. Barba R, Egeland CP (Eds.). Deconstructing Olduvai: A Taphonomic Study of the Bed I Sites[C]. Dordrecht: Springer, 2007: 23-32 |

| [18] | Courtenay LA, Yravedra J, Huguet R, et al. Combining machine learning algorithms and geometric morphometrics: A study of carnivore tooth marks[J]. Palaeogeography Palaeoclimatology Palaeoecology, 2019, 522: 28-39 |

| [19] | Blumenschine RJ. Percussion marks, tooth marks, and experimental determinations of the timing of hominid and carnivore access to long bones at FLK Zinjanthropus, Olduvai Gorge, Tanzania[J]. Journal of Human Evolution, 1995, 29: 21-51 |

| [20] | Blumenschine RJ, Marean CW, Capaldo SD. Blind Tests of Inter-analyst Correspondence and Accuracy in the Identification of Cut Marks, Percussion Marks, and Carnivore Tooth Marks on Bone Surfaces[J]. Journal of Archaeological Science, 1996, 23(4): 493-507 |

| [21] | Bunn HT. Archaeological evidence for meat-eating by Plio-Pleistocene hominids from Koobi Fora and Olduvai Gorge[J]. Nature, 1981, 291: 574-577 |

| [22] | Potts R, Shipman P. Cutmarks made by stone tools on bones from Olduvai Gorge, Tanzania[J]. Nature, 1981, 291: 577-580 |

| [23] | Shipman P. Applications of scanning electron microscopy to taphonomic problems[J]. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 1981, 376: 357-385 |

| [24] | Fisher JW. Bone surface modifications in zooarchaeology[J]. Journal of Archaeological Method Theory, 1995, 1(1):7-68 |

| [25] | Domínguez-Rodrigo M, Piqueras A. The use of tooth pits to identify carnivore taxa in tooth-marked archaeofaunas and their relevance to reconstruct hominid carcass processing behaviors[J]. Journal of Archaeological Science, 2003, 30(11): 1385-1391 |

| [26] | Blumenschine RJ, Selvaggio MM. Percussion marks on bone surfaces as a new diagnostic of hominid behavior[J]. Nature, 1988, 333: 763-765 |

| [27] | Pickering TR, Egeland CP. Experimental patterns of hammerstone percussion damage on bones: implications for inferences of carcass processing by humans[J]. Journal of Archaeological Science, 2006, 33(4): 459-469 |

| [28] | Domínguez-Rodrigo M. A study of carnivore competition in riparian and open habitats of modern savannas and its implications for hominid behavioral modeling[J]. Journal of Human Evolution, 2001, 40(2): 77-98 |

| [29] | Domínguez-Rodrigo M, Barba R. The behavioral meaning of cut marks at the FLK Zinj level: the carnivore-hominid-carnivore hypothesis falsified (II)[A]. In: Domínguez-RodrigoM, BarbaR, EgelandCP (Eds.). Deconstructing Olduvai: A Taphonomic Study of the Bed I Sites[C]. Dordrecht: Springer, 2007: 75-100 |

| [30] | Selvaggio MM. Carnivore tooth marks and stone tool butchery marks on scavenged bones: archaeological implications[J]. Journal of Human Evolution, 1994, 27(1-3): 215-228 |

| [31] | Capaldo SD. Inferring Hominid and Carnivore Behavior from Dual-Patterned Archaeological Assemblages[D]. New Brunswick: Rutgers University, 1995 |

| [32] | Capaldo SD. Experimental determinations of carcass processing by Plio-Pleistocene hominids and carnivores at FLK 22 (Zinjanthropus), Olduvai Gorge, Tanzania[J]. Journal of Human Evolution, 1997, 33: 555-597 |

| [33] | Bunn HT. Meat-Eating and Human Evolution: Studies on the Diet and Subsistence Patterns of Plio-Pleistocene Hominids in East Africa[D]. Berkeley: University of California, 1982 |

| [34] | Villa P, Mahieu E. Breakage patterns of human long bones[J]. Journal of Human Evolution, 1991, 21: 27-48. |

| [35] | Capaldo SD, Blumenschine RJ. A quantitative diagnosis of notches made by hammerstone percussion and carnivore gnawing on bovid long bones[J]. American Antiquity, 1994, 59: 724-748 |

| [36] | Coil R, Yezzi-Woodley K, Tappen M. Comparisons of impact flakes derived from hyena and hammerstone long bone breakage[J]. Journal of Archaeological Science, 2020, 105167(120): 1-9 |

| [37] | Pickering TR, Domínguez-Rodrigo M, Egeland CP, et al. The contribution of limb bone fracture patterns to reconstructing early hominid behavior at Swartkrans Cave (South Africa): Archaeological application of a new analytical method[J]. International Journal of Osteoarchaeology, 2005, 15: 247-260 |

| [38] | Parkinson JA, Plummer T, Hartstone-Rose A. Characterizing felid tooth marking and gross bone damage patterns using GIS image analysis: An experimental feeding study with large felids[J]. Journal of Human Evolution, 2015, 80: 114-134 |

| [39] | Moclán A, Domínguez-Rodrigo M, Yravedra J. Classifying agency in bone breakage: an experimental analysis of fracture planes to differentiate between hominin and carnivore dynamic and static loading using machine learning (ML) algorithms[J]. Archaeological and Anthropological Sciences, 2019, 11: 4663-4680 |

| [40] | Domínguez-Rodrigo M, Baquedano E. Distinguishing butchery cut marks from crocodile bite marks through machine learning methods[J]. Scientific Reports, 2018, 8(5786): 1-8 |

| [41] | Aramendi J, Maté-González MÁ, Yravedra J, et al. Discerning carnivore agency through the three-dimensional study of tooth pits: revisiting crocodile feeding behaviour at FLK- Zinj and FLK NN3 (Olduvai Gorge, Tanzania)[J]. Palaeogeography Palaeoclimatology Palaeoecology, 2017, 488: 93-102 |

| [42] | Pante MC, Muttart MV, Keevil TL, et al. A new high-resolution 3-D quantitative method for identifying bone surface modifications with implications for the Early Stone Age archaeological record[J]. Journal of Human Evolution, 2017, 102: 1-11 |

| [43] | Yravedra J, Maté-González MA, Palomeque-González JF, et al. A new approach to raw material use in the exploitation of animal carcasses at BK (Upper Bed II, Olduvai Gorge, Tanzania): a micro-photogrammetric and geometric morphometric analysis of fossil cut marks[J]. Boreas, 2017, 46(4): 860-873 |

| [44] | Delaney-Rivera C, Plummer TW, Hodgson JA, et al. Pits and pitfalls: taxonomic variability and patterning in tooth mark dimensions[J]. Journal of Archaeological Science, 2009, 36: 2597-2608 |

| [45] | Merritt SR. An experimental investigation of changing cut mark cross-sectional size during butchery: Implications for interpreting tool-assisted carcass processing from cut mark samples[J]. Journal of Archaeological Science: Reports, 2019, 25: 184-194 |

| [46] | Courtenay LA, Yravedra J, Aramendi J, et al. Cut marks and raw material exploitation in the lower pleistocene site of Bell’s Korongo (BK, Olduvai Gorge, Tanzania): A geometric morphometric analysis[J]. Quaternary International, 2019, 526: 155-168 |

| [47] | Arriaza MC, Domínguez-Rodrigo M, Yravedra J, et al. Lions as bone accumulators? Paleontological and ecological implications of a modern bone assemblage from Olduvai Gorge[J]. PLoS One, 2016, 11(5): e0153797 |

| [48] | Arriaza AC, Aramendi J, Maté-González MA, et al. Geometric-morphometric analysis of tooth pits and the identification of felid and hyenid agency in bone modification[J]. Quaternary International, 2019, 517: 79-87 |

| [49] | Egeland CP, Domínguez-Rodrigo M, Pickering TR, et al. Hominin skeletal part abundances and claims of deliberate disposal of corpses in the Middle Pleistocene[J]. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 2018, 115(18): 4601-4606 |

| [50] | Domínguez-Rodrigo M, Saladié P, Cáceres I, et al. (2018) Spilled ink blots the mind: A reply to Merrit et al. (2018) on subjectivity and bone surface modifications[J]. Journal of Archaeological Science, 2019, 102: 80-86 |

| [51] | Marean CW. Of taphonomy and zooarchaeology[J]. Evolutionary Anthropology, 1995, 4(2): 64-72 |

| [52] | 乔治·奥德尔. 破译史前人类的技术与行为——石制品分析[M].译者: 关莹, 陈虹. 北京: 生活·读书·新知三联书店, 2015 |

| [53] | Blasco R, Arilla M, Domínguez-Rodrigo M, et al. Who peeled the bones? An actualistic and taphonomic study of axial elements from the Toll Cave Level 4, Barcelona, Spain[J]. Quaternary Science Reviews, 2020, 250: 1-21 |

| [54] | Cidna A, Yravedra J, Domínguez-Rodrigo M. A cautionary note on the use of captive carnivores to model wild predator behavior: a comparison of bone modification patterns on long bones by captive and wild lions[J]. Journal of Archaeological Science, 2013, 40: 1903-1910 |

| [55] | Sala N, Arsuaga J, Haynes G. Taphonomic comparison of bone modifications caused by wild and captive wolves (Canis lupus)[J]. Quaternary International, 2014, 330: 126-135 |

| [56] | Domínguez-Rodrigo M, Yravedra J, Organista E. A new methodological approach to the taphonomic study of paleontological and archaeological faunal assemblages: a preliminary case study from Olduvai Gorge (Tanzania)[J]. Journal of Archaeological Science, 2015, 59: 35-53 |

| [57] | Madgwick R, Broderick LG. Taphonomies of Trajectory: the pre- and post- depositional movement of bones[J]. Archaeological and Anthropological Sciences, 2016, 8: 223-226 |

| [58] | Marchionni L, Magnín LA, Hermo DO, et al. Advances in the definition of environmental contexts in the Deseado Massif (Santa Cruz, Argentina) and its effects on the modern bone record[J]. Journal of Archaeological Science: Reports, 2020, 32: 1-13 |

| [59] | Gutierrez MA, Rafuse DJ, Alvarez MC, et al. Ten years of actualistic taphonomic research in the Pampas region of Argentina: Contributions to regional archaeology[J]. Quaternary International, 2018, 492: 40-52 |

| [60] | Arriaza MC, Organista E, Yravedra J, et al. Striped hyenas as bone modifiers in dual human-to-carnivore experimental models[J]. Archaeological and Anthropological Sciences, 2019, 11: 3187-3199 |

| [61] | Blumenschine RJ. An experimental model of the timing of hominid and carnivore influence on archaeological bone assemblages[J]. Journal of Archaeological Science, 1988, 15(5): 483-502 |

| [62] | Capaldo SD. Simulating the Formation of Dual-Patterned Archaeofaunal Assemblages with Experimental Control Samples[J]. Journal of Archaeological Science, 1998, 25: 311-330 |

| [63] | Pante MC, Blumenschine RJ, Capaldo SD, et al. Validation of bone surface modification models for inferring fossil hominin and carnivore feeding interactions, with reapplication to FLK 22, Olduvai Gorge, Tanzania[J]. Journal of Human Evolution, 2012, 63(2): 395-407 |

| [64] | Domínguez-Rodrigo M, Bunn HT, Yravedra J. A critical re-evaluation of bone surface modification models for inferring fossil hominin and carnivore interactions through a multivariate approach: application to the FLK Zinj archaeofaunal assemblage (Olduvai Gorge, Tanzania)[J]. Quaternary International, 2014, 322(323): 32-43 |

| [65] | Parkinson JA. Revisiting the hunting-versus-scavenging debate at FLK Zinj: A GIS spatial analysis of bone surface modifications produced by hominins and carnivores in the FLK 22 assemblage, Olduvai Gorge, Tanzania[J]. Palaeogeography Palaeoclimatology Palaeoecology, 2018, 511: 29-51 |

| [66] | Bunn HT, Kroll EM. Systematic butchery by Plio-Pleistocene hominids at Olduvai Gorge, Tanzania[J]. Current Anthropology, 1986, 27: 431-452 |

| [67] | Oliver JS. Estimates of hominid and carnivore involvement in the FLK Zinjanthropus fossil assemblage: some socioeconomic implications[J]. Journal of Human Evolution, 1994, 27: 267-294 |

| [68] | Domínguez-Rodrigo M. Hunting and scavenging by early humans: the state of the debate[J]. Journal of World Prehistoy, 2002, 16: 1-54 |

| [69] | Ferraro JV, Plummer TW, Pobiner BL, et al. Earliest archaeological evidence for persistent hominin carnivory[J]. PLoS One, 2013, 8(4): e62174 |

| [70] | Plummer TW, Bishop LC. Oldowan hominin behavior and ecology at Kanjera South, Kenya[J]. Journal of Anthropological Sciences, 2016, 94: 1-12 |

| [71] | Selvaggio MM. Evidence for a three-stage sequence of hominid and carnivore involvement with long bones at FLK Zinjanthropus, Olduvai Gorge, Tanzania[J]. Journal of Archaeological Science, 1998, 25: 191-202 |

| [72] | Pobiner BL. New actualistic data on the ecology and energetics of hominin scavenging opportunities[J]. Journal of Human Evolution, 2015, 80: 1-16 |

| [73] | Bunn HT. Hunting, power scavenging, and butchering by Hadza foragers and by Plio-Pleistocene Homo[A]. In StanfordCB, BunnHT (Eds.). Meat-Eating and Human Evolution[C]. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2001: 199-218 |

| [74] | Domínguez-Rodrigo M, Barba R. New estimates of tooth mark and percussion mark frequencies at the FLK Zinj site: the carnivore-hominid-carnivore hypothesis falsified[J]. Journal of Human Evolution, 2006, 50: 170-194 |

| [75] | Parkinson JA, Plummer TW, Bose R. A GIS-based approach to documenting large canid damage to bones[J]. Palaeogeography Palaeoclimatology Palaeoecology, 2014, 409: 57-71 |

| [76] | Parkinson JA, Plummer T, Hartstone-Rose A. Characterizing felid tooth marking and gross bone damage patterns using GIS image analysis: an experimental feeding study with large felids[J]. Journal of Human Evolution, 2015, 80: 114-134 |

| [77] | 陈淳. 埋藏学与骨骼破损分析[J]. 化石, 1993, 2: 3-4 |

| [78] | 张双权. 旧石器遗址动物骨骼表面非人工痕迹研究及其考古学意义[J]. 第四纪研究, 2014, 34(1): 131-140 |

| [79] | 张乐, 张双权, 高星. 地理信息系统在动物考古学研究中的应用:以贵州马鞍山遗址出土的动物遗存为例(英文)[J]. 人类学学报, 2019, 38(3): 407-418 |

/

| 〈 |

|

〉 |