化石人猿超科成员指趾骨弯曲程度与位移行为

收稿日期: 2022-04-18

修回日期: 2022-05-22

网络出版日期: 2022-08-10

基金资助

中国科学院战略性先导科技专项(XDB26000000)

Phalangeal curvature and locomotor behavior of fossil hominoids

Received date: 2022-04-18

Revised date: 2022-05-22

Online published: 2022-08-10

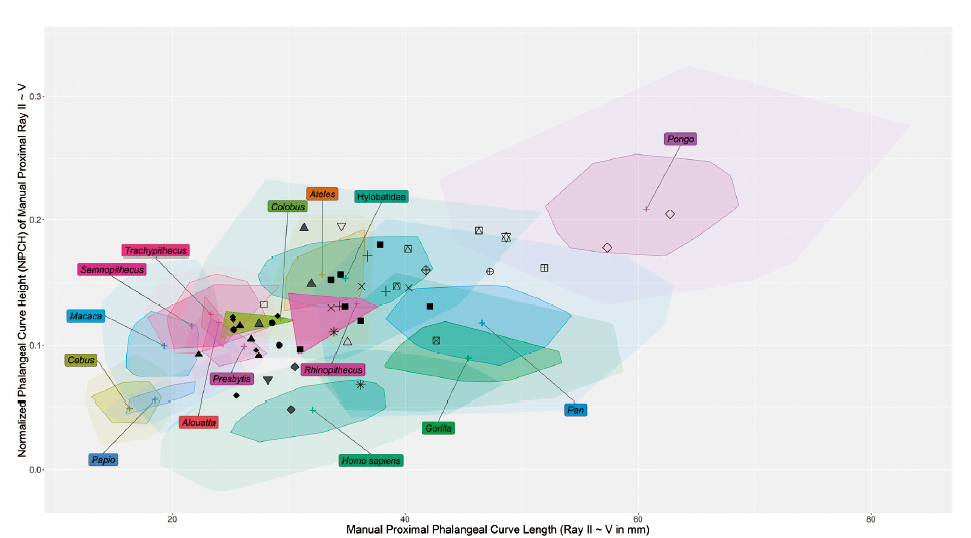

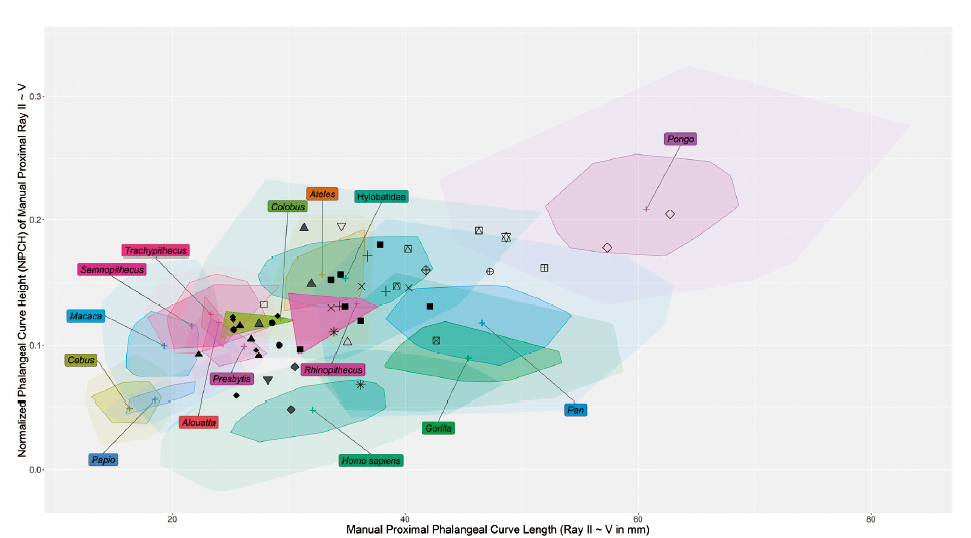

灵长类近节指趾骨的弯曲程度被认为是树栖性和悬垂位移行为的一个重要指标。几何形态测量学—多项式曲线拟合法(GM-PCF)提供了一种更加精准的指趾骨弯曲程度的定量化指标,以剔除指趾骨大小因素之后的标准化曲线高度(NPCH)作为其弯曲程度的指标,配合指趾骨的曲线长度,可以更加全面地定量分析灵长类指趾骨弯曲程度与位移行为的对应关系。尤其是涵盖灵长类大部分位移行为方式的15个类群、328个个体、5000余件指趾骨的参考样本,基本可以满足各种化石灵长类指趾骨弯曲程度分析和位移行为方式重建的需求。本文总结了发现有完整第II-V近节指趾骨化石材料的人猿超科成员的颅后骨骼形态适应及位移行为的重建,并运用GM-PCF对这些指趾骨化石的弯曲程度进行了对比分析,以通过指趾骨弯曲程度重建人猿超科成员的位移行为适应,并可为这些人猿超科成员位移行为的完整演化图景增加新的认识。

张颖奇 , Terry HARRISON . 化石人猿超科成员指趾骨弯曲程度与位移行为[J]. 人类学学报, 2022 , 41(04) : 659 -673 . DOI: 10.16359/j.1000-3193/AAS.2022.0033

Phalangeal curvature of primates is an important indicator of arboreality and suspensory locomotion. Fourth order polynomial curve fitting on geometric morphometric landmark data (GM-PCF) provides a more precise and accurate quantitative measure of phalangeal curvature, namely normalized phalangeal curve height (NPCH), which controls for the impact of size. Coupled with phalangeal curve length (PCL), NPCH maps primate phalangeal curvature to locomotor modes more accurately. Furthermore, data on phalangeal curvature derived from a sample of 15 extant anthropoid primate taxa comprising 328 individuals and more than 5000 phalangeal specimens can be used to reconstruct the locomotor behaviors of fossil primates. In this study, the postcranial morphological adaptations and locomotor behaviors of fossil hominoids with complete II-V proximal phalanges (pedal and manual) are inferred using GM-PCF analysis of phalangeal curvature. The aim is to provide new information that can contribute to a more complete understanding of the evolution of the locomotor behavior of fossil hominoids. The results indicate that generally there are four stages in the evolution of hominoid locomotor behavior, including the generalized arboreal quadrupedalism stage of basal hominoids, the arboreal suspension stage of early hominids, the commencement of bipedalism with retention of suspension ability stage of early hominins and australopiths, and the bipedalism stage of the genus Homo. The adaptation of climbing and suspension does not follow a simple linear mode, but develops in a mosaic pattern, and occurs in different lineages of hominoids through different pathways, even multiple times until it completely disappears in the end. The manual phalangeal curvature comparable to modern humans already occurred in OH 86 from the >1.84 MaBP deposits of Olduvai, whereas the nearly contemporary Paranthropus robustus from South Africa still retained more curved manual and pedal phalanges. Homo naledi also has extraordinarily curved manual phalanges. Nevertheless, locomotor behavior needs the coordination of the whole body. The phalangeal curvature is just one line of evidence of functional morphology. When reconstructing the locomotor behavior of a certain fossil hominoid taxon, it is necessary to take not only the functional morphological feature of the whole body into consideration, but also the paleo-ecological factors. Another intriguing finding of this research is that, in hominoids, the ratio of the curve length of manual to pedal proximal phalanges is indicative of obligate or facultative bipedalism when it is larger than 1.3. In general, the more quadrupedal primates tend to have a ratio that is closer to 1, which means that their manual and pedal proximal phalanges have a similar curve length. However, Pongo is an exception, because it has a ratio of 1.03 in spite of being highly suspensory. Hylobatids and great apes other than Pongo all have a ratio larger than 1.3 and all engage in obligate or facultative bipedalism. If this is the case, the early hominin Ardipithecus ramidus, the australopiths Australopithecus afarensis and Australopithecus africanus, and Homo floresiensis should also have engaged in certain kinds of bipedalism.

Key words: hominoids; phalangeal curvature; locomotor behavior; functional morphology; GM-PCF; bipedality

| [1] | Zhang Y, Harrison T, Ji X. Inferring the locomotor behavior of fossil hominoids from phalangeal curvature using a novel method: Lufengpithecus as a case study[J]. Acta Anthropologica Sinica, 2020, 39(4): 542-563 |

| [2] | Richmond BG. Biomechanics of phalangeal curvature[J]. Journal of Human Evolution, 2007, 53(6): 678-690 |

| [3] | Ward CV. Interpreting the posture and locomotion of Australopithecus afarensis: Where do we stand?[J]. Yearbook of Physical Anthropology, 2002, 45: 185-215 |

| [4] | Begun DR. The Miocene hominoid radiations[A]. In: Begun DR (Ed.). A companion to paleoanthropology[M]. Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell, 2013, 398-416 |

| [5] | Begun DR. Fossil record of Miocene hominoids[A]. In: Henke W, Tattersall I (Eds.). Handbook of paleoanthropology[M]. New York: Springer, 2015, 1261-1332 |

| [6] | Harrison T. Dendropithecoidea, Proconsuloidea, and Hominoidea (Catarrhini, Primates)[A]. In: Werdelin L, Sanders WJ (Eds.). Cenozoic mammals of Africa[M]. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2010, 429-469 |

| [7] | ScNPCHeider CA, Rasband WS, Eliceiri KW. NIH Image to ImageJ: 25 years of image analysis[J]. Nature Methods, 2012, 9(7): 671-675 |

| [8] | Jungers WL, Larson SG, Harcourt-Smith W, et al. Descriptions of the lower limb skeleton of Homo floresiensis[J]. Journal of Human Evolution, 2009, 57(5): 538-554 |

| [9] | R Core Team. R: A language and environment for statistical computing[CP/OL]. URL: https://www.R-project.org/. 2022 |

| [10] | Ward CV. Postcranial and locomotor adaptations of hominoids[A]. In: Henke W, Tattersall I (Eds.). Handbook of Paleoanthropology[M]. New York: Springer, 2015, 1363-1386 |

| [11] | Nakatsukasa M, Almécija S, Begun DR. The hands of Miocene hominoids[A]. In: Kivell TL, Lemelin P, Richmond BG, et al. (Eds.). The evolution of the primate hand[M]. New York: Springer, 2016, 485-514 |

| [12] | de Bonis L, Koufos GD. First discovery of postcranial bones of Ouranopithecus macedoniensis (Primates, Hominoidea) from the late Miocene of Macedonia (Greece)[J]. Journal of Human Evolution, 2014, 74: 21-36 |

| [13] | Rook L, Renne P, Benvenuti M, et al. Geochronology of Oreopithecus-bearing succession at Baccinello (Italy) and the extinction pattern of European Miocene hominoids[J]. Journal of Human Evolution, 2000, 39(6): 577-582 |

| [14] | Böhme M, Spassov N, Fuss J, et al. A new Miocene ape and locomotion in the ancestor of great apes and humans[J]. Nature, 2019, 575(7783): 489-493 |

| [15] | 徐庆华, 陆庆五. 禄丰古猿-人科早期成员[M]. 北京: 科学出版社, 2008 |

| [16] | Begun DR, Kivell TL. Knuckle-walking in Sivapithecus? The combined effects of homology and homoplasy with possible implications for pongine dispersals[J]. Journal of Human Evolution, 2011, 60(2): 158-170 |

| [17] | Haile-Selassie Y. Late Miocene hominids from the Middle Awash, Ethiopia[J]. Nature, 2001, 412(6843): 178-181 |

| [18] | Haile-Selassie Y, Suwa G, White TD. Late Miocene teeth from Middle Awash, Ethiopia, and early hominid dental evolution[J]. Science, 2004, 303(5663): 1503-1505 |

| [19] | Senut B. The Miocene hominoids and the earliest putative hominids[A]. In: Henke W, Tattersall I (Eds.). Handbook of Paleoanthropology[M]. New York: Springer, 2015, 2043-2070 |

| [20] | White TD, Asfaw B, Beyene Y, et al. Ardipithecus ramidus and the Paleobiology of Early Hominids[J]. Science, 2009, 326: 75-86 |

| [21] | Lovejoy CO, Simpson SW, White TD, et al. Careful climbing in the Miocene: the forelimbs of Ardipithecus ramidus and humans are primitive[J]. Science, 2009, 326(5949): 70-70e8 |

| [22] | Lovejoy CO, Latimer B, Suwa G, et al. Combining Prehension and Propulsion: The Foot of Ardipithecus ramidus[J]. Science, 2009, 326(5949): 72-72e8 |

| [23] | Prang TC, Ramirez K, Grabowski M, et al. Ardipithecus hand provides evidence that humans and chimpanzees evolved from an ancestor with suspensory adaptations[J]. Science Advances, 2021, 7(9): eabf2774 |

| [24] | Kimbel WH. The species and diversity of australopiths[A]. In: Henke W, Tattersall I (Eds.). Handbook of paleoanthropology[M]. New York: Springer, 2015, 2071-2105 |

| [25] | Georgiou L, Dunmore CJ, Bardo A, et al. Evidence for habitual climbing in a Pleistocene hominin in South Africa[J]. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 2020, 117(15): 8416-8423 |

| [26] | Berger LR, de Ruiter DJ, Churchill SE, et al. Australopithecus sediba: a new species of Homo-like australopith from South Africa[J]. Science, 2010, 328(5975): 195-204 |

| [27] | Churchill SE, Holliday TW, Carlson KJ, et al. The upper limb of Australopithecus sediba[J]. Science, 2013, 340(6129): 1233477 |

| [28] | DeSilva JM, Holt KG, Churchill SE, et al. The lower limb and mechanics of walking in Australopithecus sediba[J]. Science, 2013, 340(6129): 1232999 |

| [29] | Rein TR, Harrison T, Carlson KJ, et al. Adaptation to suspensory locomotion in Australopithecus sediba[J]. Journal of Human Evolution, 2017, 104: 1-12 |

| [30] | Ryan TM, Carlson KJ, Gordon AD, et al. Human-like hip joint loading in Australopithecus africanus and Paranthropus robustus[J]. Journal of Human Evolution, 2018, 121: 12-24 |

| [31] | Domínguez-Rodrigo M, Pickering TR, Almécija S, et al. Earliest modern human-like hand bone from a new > 1.84-million-year-old site at Olduvai in Tanzania[J]. Nature Communications, 2015, 6(1): 8987 |

| [32] | Lorenzo C, Pablos A, Carretero JM, et al. Early Pleistocene human hand phalanx from the Sima del Elefante (TE) cave site in Sierra de Atapuerca (Spain)[J]. Journal of Human Evolution, 2015, 78: 114-121 |

| [33] | Berger LR, Hawks J, de Ruiter DJ, et al. Homo naledi, a new species of the genus Homo from the Dinaledi Chamber, South Africa[J]. eLife, 2015, 4: e09560 |

| [34] | Dirks PH, Roberts EM, Hilbert-Wolf H, et al. The age of Homo naledi and associated sediments in the Rising Star Cave, South Africa[J]. eLife, 2017, 6: e24231 |

| [35] | Harcourt-Smith WEH, Throckmorton Z, Congdon KA, et al. The foot of Homo naledi[J]. Nature Communications, 2015, 6(1): 8432 |

| [36] | Marchi D, Walker CS, Wei P, et al. The thigh and leg of Homo naledi[J]. Journal of Human Evolution, 2017, 104: 174-204 |

| [37] | Kivell TL, Deane AS, Tocheri MW, et al. The hand of Homo naledi[J]. Nature Communications, 2015, 6(1): 8431 |

| [38] | Brown P, Sutikna T, Morwood MJ, et al. A new small-bodied hominin from the Late Pleistocene of Flores, Indonesia[J]. Nature, 2004, 431(7012): 1055-1061 |

| [39] | Sutikna T, Tocheri MW, Morwood MJ, et al. Revised stratigraphy and chronology for Homo floresiensis at Liang Bua in Indonesia[J]. Nature, 2016, 532(7599): 366-369 |

| [40] | Blaszczyk MB, Vaughan CL. Re-interpreting the evidence for bipedality in Homo floresiensis[J]. South African Journal of Science, 2007, 103(9-10): 409-414 |

| [41] | Nakatsukasa M, Kunimatsu Y, Nakano Y, et al. Comparative and functional anatomy of phalanges in Nacholapithecus kerioi, a Middle Miocene hominoid from northern Kenya[J]. Primates, 2003, 44: 371-412 |

| [42] | Ersoy A, Kelley J, Andrews P, et al. Hominoid phalanges from the middle Miocene site of Pasalar, Turkey[J]. Journal of Human Evolution, 2008, 54(4): 518-529 |

| [43] | Almécija S, Alba DM, Moyà-Solà S. Pierolapithecus and the functional morphology of Miocene ape hand phalanges: paleobiological and evolutionary implications[J]. Journal of Human Evolution, 2009, 57(3): 284-297 |

| [44] | Almécija S, Alba DM, Moyà-Solà S, et al. Orang-like manual adaptations in the fossil hominoid Hispanopithecus laietanus: first steps towards great ape suspensory behaviours[J]. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 2007, 274(1624): 2375-2384 |

| [45] | Moyà-Solà S, Köhler M, Alba DM, et al. Pierolapithecus catalaunicus, a new Middle Miocene great ape from Spain[J]. Science, 2004, 306(5700): 1339-1344 |

| [46] | Begun DR. New catarrhine phalanges from Rudabánya (Northeastern Hungary) and the problem of parallelism and convergence in hominoid postcranial morphology[J]. Journal of Human Evolution, 1993, 24(5): 373-402 |

| [47] | Susman RL. Oreopithecus bambolii: an unlikely case of hominidlike grip capability in a Miocene ape[J]. Journal of Human Evolution, 2004, 46(1): 105-117 |

| [48] | Rose MD. Further hominoid postcranial specimens from the Late Miocene Nagri Formation of Pakistan[J]. Journal of Human Evolution, 1986, 15(5): 333-367 |

| [49] | MacLatchy LM, DeSilva J, Sanders WJ, et al. Hominini[A]. In: Werdelin L, Sanders WJ (Eds.). Cenozoic mammals of Africa[M]. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2010, 471-545 |

| [50] | Bush ME, Lovejoy CO, Johanson DC, et al. Hominid carpal, metacarpal, and phalangeal bones recovered from the Hadar Formation: 1974-1977 collections[J]. American Journal of Physical Anthropology, 1982, 57(4): 651-677 |

| [51] | Johanson DC, Lovejoy CO, Kimbel WH, et al. Morphology of the Pliocene partial hominid skeleton (A.L. 288-1) from the Hadar formation, Ethiopia[J]. American Journal of Physical Anthropology, 1982, 57(4): 403-451 |

| [52] | Latimer BM, Lovejoy CO, Johanson DC, et al. Hominid tarsal, metatarsal, and phalangeal bones recovered from the Hadar Formation: 1974-1977 collections[J]. American Journal of Physical Anthropology, 1982, 57(4): 701-719 |

| [53] | Kivell TL, Kibii JM, Churchill SE, et al. Australopithecus sediba hand demonstrates mosaic evolution of locomotor and manipulative abilities[J]. Science, 2011, 333(6048): 1411-1417 |

| [54] | Kivell TL, Ostrofsky KR, Richmond BG, et al. Metacarpals and manual phalanges[A]. In: Zipfel B, Richmond BG, Ward CV (Eds.). Hominin postcranial Remains from Sterkfontein, South Africa, 1936-1995[M]. New York: Oxford University Press, 2020, 106-143 |

| [55] | Pickering TR, Heaton JL, Clarke RJ, et al. Hominin hand bone fossils from Sterkfontein Caves, South Africa (1998-2003 excavations)[J]. Journal of Human Evolution, 2018, 118: 89-102 |

| [56] | Zipfel B, Wunderlich R. Metatarsals and pedal phalanges[A]. In: Zipfel B, Richmond BG, Ward CV (Eds.). Hominin postcranial remains from Sterkfontein, South Africa, 1936-1995[M]. New York: Oxford University Press, 2020, 289-303 |

| [57] | Kivell TL, Churchill SE, Kibii JM, et al. Special Issue: Australopithecus sediba - The hand of Australopithecus sediba[J]. PaleoAnthropology, 2018, 2018: 282-333 |

| [58] | Susman RL. New Hominid Fossils from the Swartkrans Formation (1979-1986 Excavations) - Postcranial Specimens[J]. American Journal of Physical Anthropology, 1989, 79(4): 451-474 |

| [59] | Susman RL, de Ruiter D, Brain CK. Recently identified postcranial remains of Paranthropus and Early Homo from Swartkrans Cave, South Africa[J]. Journal of Human Evolution, 2001, 41(6): 607-629 |

| [60] | Larson SG, Jungers WL, Tocheri MW, et al. Descriptions of the upper limb skeleton of Homo floresiensis[J]. Journal of Human Evolution, 2009, 57(5): 555-570 |

/

| 〈 |

|

〉 |