楔形细石核压制剥片技术的实验研究

收稿日期: 2022-03-18

修回日期: 2022-05-16

网络出版日期: 2023-06-13

基金资助

国家重点研发计划(2020YFC1521500);中国科学院战略性先导科技专项(XDB26000000);中国科学院国际伙伴计划项目(132311KYSB20190008);考古中国—吉林东部长白山地区古人类遗址调查与研究

An experimental study of the flaking-by-pressing technology of wedge-shaped microcores

Received date: 2022-03-18

Revised date: 2022-05-16

Online published: 2023-06-13

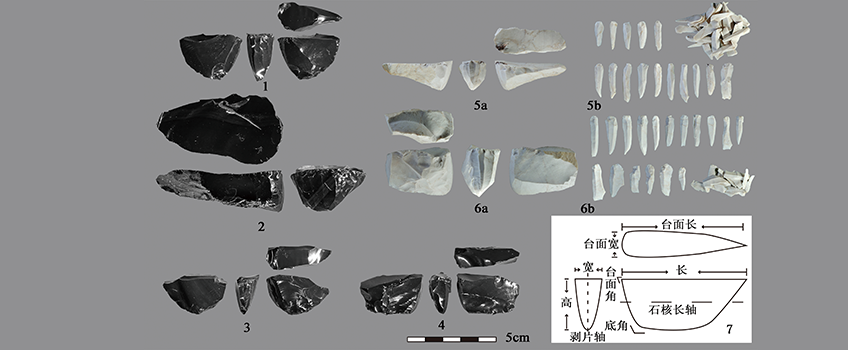

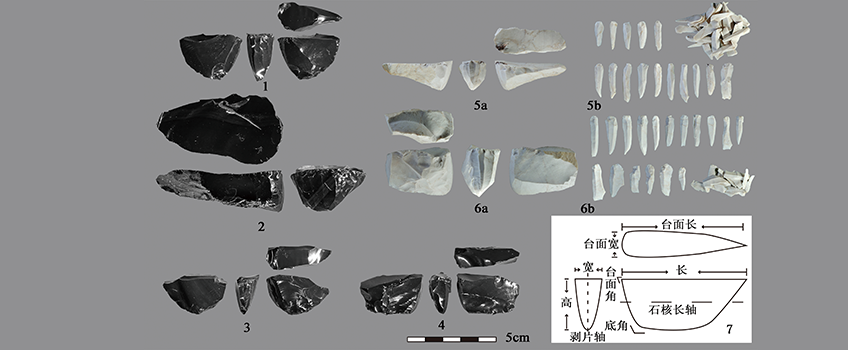

楔形细石核技术是东北亚旧石器时代晚期细石叶剥片技术的典型代表,具有重要的学术价值。本文参考泥河湾盆地旧石器时代晚期常见的湧别系技术,设计了细石叶剥离实验,并检验了剥片面宽度、棱脊高低、杆尖粗细和固定方式等多个变量与细石叶形态的关系,揭示了连续剥制规范细石叶的技术要素。实验结果表明,棱脊是影响细石叶形态的关键因素之一,只有利用较高的棱脊才能连续地剥取规整的产品;为了维持较高的棱脊,细石核的剥片面不宜太宽,否则棱脊将变矮,影响规则细石叶的连续生产;使用压制法剥取细石叶时,细尖压杆更能有效、稳定地利用棱脊;对楔形细石核的固定实验表明,楔状缘有用来加固石核以达稳定之目的。本次实验描述了楔形细石核剥片的多项技术细节,为今后理解考古材料中的相关发现,并为讨论细石叶技术的起源、扩散和适应等提供了有益参考。

仝广 , 李锋 , 高星 . 楔形细石核压制剥片技术的实验研究[J]. 人类学学报, 2023 , 42(03) : 305 -316 . DOI: 10.16359/j.1000-3193/AAS.2023.0009

Wedge-shaped microblade cores are typical representatives of Upper Paleolithic microlithic assemblages in Northeast Asia. Core reduction technology of these nuclei has been investigated for over a century generating many noteworthy achievements. However, disputes regarding some fundamental aspects of this technology are still under discussion. This paper documents pressure flaking experiments on wedge-shaped microblade cores replicating artifacts discovered in Upper Paleolithic sites in the Nihewan Basin. Experiments were designed to test relationships between technological and morphological variables and microblade morphology. Such variables included the working point of pressure-flaking implements, width of the flaking surface, arris height, and vices or other means of securing nuclei in place. Based on these variables, five groups were compared with one another. Microblade cores in the standard group have a narrower working face and higher arris, and were fixed in a V-shaped device with microblades produced by use of a thin-tipped pressure flaker. Other groups showed differences in one of these variables otherwise keeping consistent with the standard group. For example, microblade cores in the low arris group only made the arris itself lower, while their working face, method of fixing and pressure flaking tool utilized are same as the standard group.

Conventional linear and geometric morphometric data on microblades were collected to analyze the degree of standardization of microblade morphology among different experimental groups. The main linear measurements were width and thickness of microblades and platform width and thickness. Geometric morphometric analysis was undertaken using Elliptic Fourier Analysis (EFA). All results revealed specific group-level differences regarding shape and standardization of microblades.

Microblade morphology is affected by several factors such as arris height, working face width, diameter of the pressure-flaker point, the form of vice employed, etc. Regular microblades can be continually produced only by utilizing a higher arris, which is achieved by ensuring the working face of microblade cores is not too wide, otherwise the height of the arris would decrease and interfere with subsequent manufacture of microblades. A thin, pointed pressure-flaking tool makes more effective use of the arris than a thick, pointed tool to remove microblades. Experiments with various means of fixing wedge-shaped microblade cores demonstrates that the core’s bottom edge is primarily employed to stabilize the stone nucleus throughout the process of microblade production. Results of the experiments reported here provide new information on microblade production and sheds light on the dispersal of microblade technology in Northeast Asia.

Key words: Archaeology; Lithics; Experimental; Knapping; Pressure; Microblades

| [1] | 陈淳. 中国细石核类型和工艺初探——兼谈与东北亚、西北美的文化联系[J]. 人类学学报, 1983, 2(4): 331-341 |

| [2] | 王建, 王益人. 下川细石核形制研究[J]. 人类学学报, 1991, 10(1): 1-8 |

| [3] | 安志敏. 中国细石器发现一百年[J]. 考古, 2000, 5: 45-56 |

| [4] | 陈胜前. 细石叶工艺的起源——一个理论与生态的视角[J]. 考古学研究, 2008, 244-264 |

| [5] | Flenniken JJ. The paleolithic Dyuktai pressure blade technique of siberia[J]. Arctic Anthropology, 1987, 24(2): 117-132 |

| [6] | 王幼平. 华北旧石器晚期环境变化与人类迁徙扩散[J]. 人类学学报, 2018, 37(3): 341-351 |

| [7] | 王幼平. 华北细石器技术的出现与发展[J]. 人类学学报, 2018, 37(4): 565-576 |

| [8] | 靳英帅, 张晓凌, 仪明洁. 楔形石核概念内涵与细石核分类初探[J]. 人类学学报, 2021, 40(2): 307-319 |

| [9] | Turq A, Roebroeks W, Bourguignon L, et al. The fragmented character of middle palaeolithic stone tool technology[J]. Journal of human evolution, 2013, 65(5): 641-655 |

| [10] | Ohnuma K. Exprerimental studies in the determination of manners of micro-blade detachment[J]. Al-Rafidan, 1993, 14: 477-494 |

| [11] | Tabarev AV. Paleolithic wedge-shaped microcores and experiments with pocket devices[J]. Lithic technology, 1997, 22(2): 139-149 |

| [12] | 赵海龙. 细石叶剥制实验研究[J]. 人类学学报, 2011, 30(1): 22-31 |

| [13] | Pelegrin J. New Experimental Observations for the Characterization of Pressure Blade Production Techniques[M]. In: Desrosiers P M. The Emergence of Pressure Blade Making: From Origin to Modern Experimentation, 2012, 465-500 |

| [14] | 大場正善. 細石刃核をどう持つか(2):南九州出土細石刃関連資料を中心とした同さ連鎖に基づく石器技術学分析[J]. 鹿儿岛考古, 2019(49): 31-44 |

| [15] | 大場正善. 細石刃核をどう持つか:北海道奥白滝ⅰ遺跡と上白滝8 遺跡の細石刃資料の動作連鎖概念に基づく技術学的分析[J]. 旧石器研究, 2014(10): 41-66 |

| [16] | Gómez Coutouly YA. The emergence of pressure knapping microblade technology in Northeast Asia[J]. Radiocarbon, 2018, 60(3): 821-855 |

| [17] | 盖培, 卫奇. 虎头梁旧石器时代晚期遗址的发现[J]. 古脊椎动物与古人类, 1977, 15(4): 287-300 |

| [18] | 陈宥成, 曲彤丽. 旧大陆东西方比较视野下的细石器起源再讨论[J]. 华夏考古, 2018(5): 37-43 |

| [19] | Lin SC, Rezek Z, Dibble HL. Experimental design and experimental inference in stone artifact archaeology[J]. Journal of Archaeological Method and Theory, 2018, 25(3): 663-688 |

| [20] | Bleed P. Cheap, Regular, and Reliable: Implications of design variation in late pleistocene japanese microblade technology[J]. Archeological papers of the American Anthropological Association, 2002, 12(1): 95-102 |

| [21] | Kuhl FP, Giardina CR. Elliptic Fourier Features of a Closed Contour[J]. Computer graphics and image processing, 1982, 18(3): 236-258 |

| [22] | Ferson S, Rohlf FJ, Koehn RK. Measuring shape variation of two-dimensional outlines[J]. Systematic Biology, 1985, 34(1): 59-68 |

| [23] | Rezek Z, Lin S, Iovita R, et al. The relative effects of core surface morphology on flake shape and other attributes[J]. Journal of Archaeological Science, 2011, 38(6): 1346-1359 |

| [24] | Hoggard CS, McNabb J, Cole JN. The application of Elliptic Fourier analysis in understanding biface shape and symmetry through the British Acheulean[J]. Journal of Paleolithic Archaeology, 2019, 2(2): 115-133 |

| [25] | Radinovi? M, Kajtez I. Outlining the knapping techniques: Assessment of the shape and regularity of prismatic blades using Elliptic Fourier analysis[J]. Journal of Archaeological Science: Reports, 2021, 38: 103079 |

| [26] | Bonhomme V, Picq S, Gaucherel C, et al. Momocs: Outline analysis using R[J]. Journal of Statistical Software, 2014, 56(13): 1-24 |

/

| 〈 |

|

〉 |