收稿日期: 2024-03-03

修回日期: 2024-05-10

网络出版日期: 2024-11-28

基金资助

国家社会科学基金(23CKG029)

Evolution of Pleistocene human femora in East Asia

Received date: 2024-03-03

Revised date: 2024-05-10

Online published: 2024-11-28

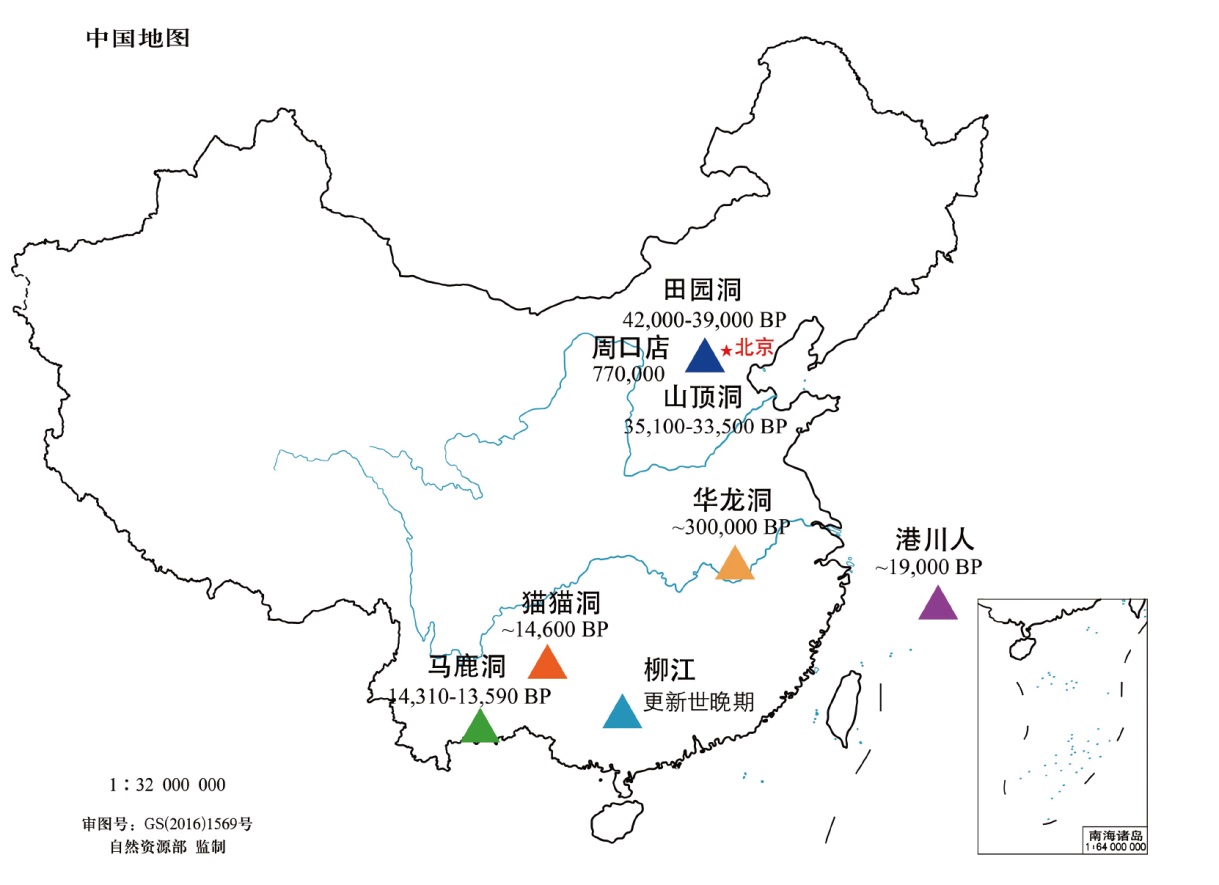

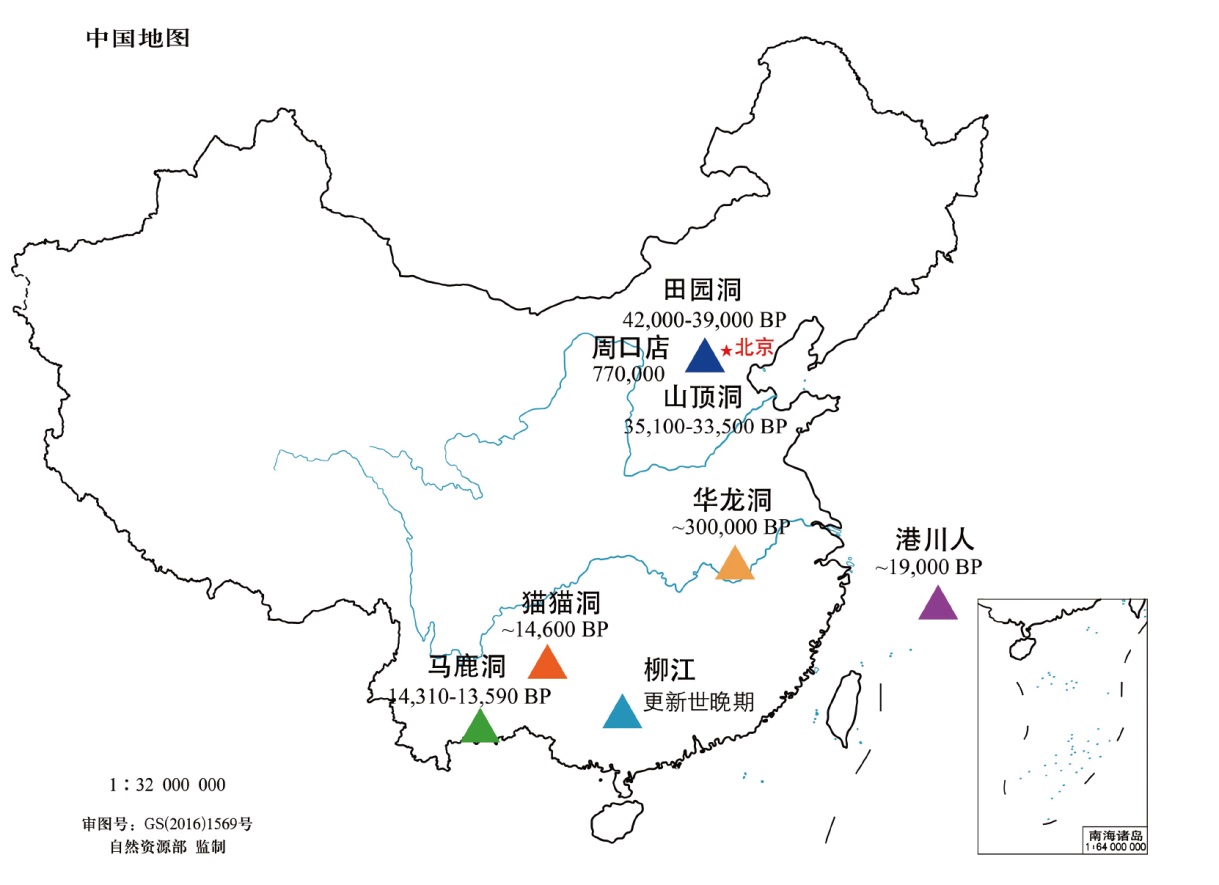

更新世古人类股骨干的形态特征对于理解人类的运动行为和体型进化具有重要意义。东亚地区此类化石稀缺且分布分散,增加了研究难度。本文系统对比了东亚更新世古人类股骨的形态差异,发现从早期到晚期,股骨干中部形态特征的变化与其他地区一致,表现为力学形状指数增大和横断面轮廓的变化,这可能与骨盆和股骨结构的演化有关。早中期的股骨粗壮度与其他地区相似,表明东亚古人类具有典型的狩猎采集者体型。然而,在更新世晚期,尽管东亚古人类股骨显示出与晚更新世现代人相似的特征,如股骨嵴和臀肌凸起,但其粗壮度低于欧洲/西亚地区,可能与行为活动或体型差异有关。这些发现为完善东亚地区人类演化史提供了重要补充。

魏偏偏 , 赵昱浩 . 东亚地区更新世古人类股骨的演化[J]. 人类学学报, 2024 , 43(06) : 993 -1005 . DOI: 10.16359/j.1000-3193/AAS.2024.0083

Investigation into morphological traits of femoral shafts from Pleistocene Homo sapiens is pivotal to our understanding of human movement patterns and body size of the East Asia type. Despite the critical role these fossils play, their scarcity and uneven distribution in East Asia pose a formidable challenge to this study of morphological evolution. This paper integrates published anatomical data with a systematic examination of midshaft cross sections and overall morphological structure of Pleistocene human femoral shafts from East Asia. This study shows a consistent trend in morphological changes from the early to late Pleistocene, mirroring anatomical patterns observed globally. For instance, the mechanical shape index of the femoral shaft increases, and the cross-sectional shape transitions from anterior-posterior elongation to medial-lateral elongation suggesting an evolutionary adaptation to changes in pelvic and femoral structures. Early and middle Pleistocene femora exhibit robusticity akin to those remains from other regions likely indicative of a common hunting-gathering lifestyle.

However, into the Late Pleistocene East Asia femora display a suite of features that align with those of Late Pleistocene modern humans elsewhere, including a pronounced femoral pilaster and gluteal buttress, elongation of the midshaft cross section in an anterior-posterior direction, and a thickening of the posterior shaft wall from mid-distal to mid-proximal, enhancing anterior-posterior and lateral bending rigidity. Robusticity of East Asia femora is notably lower than that observed in Europe and west Asia. This discrepancy may be attributed to a variety of factors, such as differences in behavioral activities or body size. It is plausible that the disparity in robusticity reflects distinct evolutionary pressures and adaptive responses to specific environmental conditions and subsistence strategies prevalent in these regions. Implications of these findings extend beyond mere cataloging of morphological traits; instead they offer insights into complex interplay between genetic predispositions, environmental influences, and behavioral adaptations that have all sculpted human evolution. The study underscores the importance of regional variations in the evolutionary process and a need for a holistic approach to understanding human evolution that takes into account unique adaptations of human populations. In conclusion, the detailed analysis of Pleistocene human femora in East Asia enriches our understanding of human locomotory behavior and body size evolution as well as highlighting regional differences.

This research contributes to a more nuanced appreciation of the diverse evolutionary pathways that have shaped anatomical and physiological characteristics of modern humans. The study encourages further exploration into morphological adaptations that have emerged in response to specific environmental and behavioral challenges faced by human populations.

| [1] | Brian GR, William LJ. Orrorin tugenensis femoral morphology and the evolution of hominin bipedalism[J]. Science, 2008, 319(5870): 1662-1665 |

| [2] | Carlson KJ, Marchi D. Reconstructing Mobility: Enviromental, Behavioral, and Morphological Feterminants[M]. Brtlin: Springer, 2014 |

| [3] | Ruff CB, Sylvester AD, Rahmawati NT, et al. Two Late Pleistocene human femora from Trinil, Indonesia: Implications for body size and behavior in Southeast Asia[J]. Journal of Human Evolution, 2022, 172: 103252 |

| [4] | Stock JT. Hunter-gatherer postcranial robusticity relative to patterns of mobility, climatic adaptation, and selection for tissue economy[J]. American Journal of Physical Anthropology, 2006, 131(2): 194-204 |

| [5] | Wei P, Wallace IJ, Jashashvili T, et al. Structural analysis of the femoral diaphyses of an early modern human from Tianyuan Cave, China[J]. Quaternary International, 2017, 434: 48-56 |

| [6] | 魏偏偏. 云南丽江古人类股骨的形态结构[J]. 人类学学报, 2020, 93(4): 616-631 |

| [7] | Wei P, Weng Z, Carlson KJ, et al. Late Pleistocene partial femora from Maomaodong, southwestern China[J]. Journal of Human Evolution, 2021, 155: 102977 |

| [8] | Xing S, Wu XJ, Liu W, et al. Middle Pleistocene human femoral diaphyses from Hualongdong, Anhui Province, China[J]. American Journal of Physical Anthropology, 2021, 174(2): 285-298 |

| [9] | Wei P, Ma S, Carlson KJ, et al. A structural reassessment of the Late Pleistocene femur from Maludong, southwestern China[J]. American Journal of Biological Anthropology, 2022, 1-12 |

| [10] | Wei P, Cazenave M, Zhao Y, et al. Structural properties of the Late Pleistocene Liujiang femoral diaphyses from southern China[J]. Journal of Human Evolution, 2023, 183, 103424 |

| [11] | Harmon EH. The shape of the early hominin proximal femur[J]. American Journal of Physical Anthropology, 2009, 139(2), 154-171 |

| [12] | Trinkaus E, Ruff CB. Diaphyseal cross-sectional morphology and biomechanics of the Fond-de-Forêt 1 femur and the Spy 2 femur and tibia[J]. Bulletin de La Société Royale Belge d’Anthropologie et de Préhistoire, 1989, 100: 33-42 |

| [13] | Trinkaus E, Ruff CB. Femoral and tibial diaphyseal cross-Sectional geometry in Pleistocene Homo[J]. PaleoAnthropology, 2012, 13-62 |

| [14] | Puymerail L, Volpato V, Debénath A, et al. A Neanderthal partial femora diaphysis from the “Grotte de la Tour”, La Chaise-de-Vouthon (Charente, France): Outer morphology and endostructural organization[J]. Comptes Rendus Palevol, 2012, 11(8): 581-593 |

| [15] | Ruff CB. Long bone articular and diaphyseal structure in old world monkeys and apes. I: Locomotor effects[J]. American Journal of Physical Anthropology, 2002, 119(4): 305-342 |

| [16] | McCown TD, Keith A. The Stone Age of Mount Carmel II: The Fossil Human Remains from the Levalloiso Mousterian[M]. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1939 |

| [17] | Trinkaus E. Early modern humans[J]. Annual Review of Anthropology, 2005, 34: 207-230 |

| [18] | Liu W, Martinón-Torres M, Kaifu Y, et al. A mandible from the Middle Pleistocene Hexian site and its significance in relation to the variability of Asian Homo erectus[J]. American Journal of Physical Anthropology, 2017, 162: 715-731 |

| [19] | Wu X, Trinkaus E. The Xujiayao 14 mandibular ramus and Pleistocene Homo mandibular variation[J]. Comptes Rendus Palevol, 2014, 13(4): 333-341 |

| [20] | Xing S, O’Hara M, Guatelli-Steinberg D, et al. Dental scratches and handedness in East Asian early Pleistocene Hominins[J]. International Journal of Osteoarchaeology, 2017, 27(6): 937-946 |

| [21] | 刘武, 吴秀杰, 邢松, 等. 中国古人类化石(第一版)[M]. 北京: 科学出版社, 2014, 347-350 |

| [22] | Chevalier T, ?z?elik K, De Lumley MA, et al. The endostructural pattern of a middle Pleistocene human femoral diaphysis from the Karain E site (Southern Anatolia, Turkey)[J]. American Journal of Physical Anthropology, 2015, 157(4): 648-658 |

| [23] | Puymerail L, Ruff CB, Bondioli L, et al. Structural analysis of the Kresna 11 Homo erectus femoral shaft (Sangiran, Java)[J]. Journal of Human Evolution, 2012, 63(5): 741-749 |

| [24] | Barshay-Szmidt C, Costamagno S, Henry-Gambier D, et al. New extensive focused AMS 14C dating of the Middle and Upper Magdalenian of the western Aquitaine/Pyrenean region of France (ca. 19-14 ka cal BP): Proposing a new model for its chronological phases and for the timing of occupation[J]. Quaternary International, 2016, 414: 62-91 |

| [25] | Couchoud I. étude Pétrographique et Isotopique de Spéléothèmes du Sud-Ouest de la France Formés en Contexte Archéologique: Contribution à la Connaissance des Paléoclimats Régionaux du Stade Isotopique 5[D]. Ph.D. Dissertation, University of Bordeaux, 2006 |

| [26] | Matsu’ura S, Kondo M, Danhara T, et al. Age control of the first appearance datum for Javanese Homo erectus in the Sangiran area[J]. Science, 367(6474), 2020: 210-214. |

| [27] | Shang H, Trinkaus E. The Early Modern Human from Tianyuan Cave, China[M]. Texas A&M University Press, College Station, 2010 |

| [28] | Vieillevigne E, Bourguignon L, Ortega I, et al. Analyse croisée des données chronologiques et des industries lithiques dans le grand sud-ouest de la France (OIS 10 à 3)[J]. PALEO, 2008, 20: 145-166 |

| [29] | Ruff CB, Hayes W. Cross-sectional geometry of Pecos Pueblo femora and tibiae—A biomechanical investigation: I. Method and general patterns of variation[J]. American Journal of Physical Anthropology, 1983, 60: 359-381 |

| [30] | Wei P, Lu H, Carlson KJ, et al. The upper limb skeleton and behavioral lateralization of modern humans from Zhaoguo Cave, southwestern China[J]. American Journal of Physical Anthropology, 2020, 173(4): 671-696. |

| [31] | Slice DE. Geometric morphometrics[J]. Annual Review of Anthropology, 2007, 36: 261-281 |

| [32] | 魏偏偏, 邢松. 云南丽江古人类股骨的形态结构[J]. 人类学学报, 2013, 32(3): 354-364 |

| [33] | Morimoto N, Ponce de Leon MS, Zollikofer CP. Exploring femoral diaphyseal shape variation in wild and captive chimpanzees by means of morphometric mapping: a test of Wolff’s law[J]. Anat Rec (Hoboken), 2011, 294(4), 589-609. |

| [34] | Bondioli L, Bayle P, Dean C, et al. Technical note: Morphometric maps of long bone shafts and dental roots for imaging topographic thickness variation[J]. American Journal of Physical Anthropology, 2010, 142(2): 328-34 |

| [35] | Trinkaus E. Modern human versus Neandertal evolutionary distinctiveness[J]. Current Anthropology, 2006, 47(4): 597-620 |

| [36] | Macintosh AA, Stock JT. Intensive terrestrial or marine locomotor strategies are associated with inter- and intra-limb bone functional adaptation in living female athletes[J]. American Journal of Physical Anthropology, 2019, 168(3): 566-581 |

| [37] | Shaw CN, Stock JT. Habitual throwing and swimming correspond with upper limb diaphyseal strength and shape in modern human athletes[J]. American Journal of Physical Anthropology, 2009, 140(1): 160-172 |

| [38] | Weatherholt AM, Warden SJ. Tibial bone strength is enhanced in the jump leg of collegiate-level jumping athletes: A within-subject controlled cross-sectional study[J]. Calcified Tissue International, 2016, 98(2): 129-139 |

/

| 〈 |

|

〉 |