乌兰木伦遗址非完整骨骼成因的实验考古学

收稿日期: 2023-07-30

修回日期: 2024-01-05

网络出版日期: 2025-02-13

基金资助

中央高校创新人才培育计划-青年拔尖人才项目(23wkqb02);中国科学院战略性先导科技专项(XDB26000000);国家自然科学基金(41977379)

An experimental archaeological study of the formation causes of incomplete bones from the Wulanmulun site

Received date: 2023-07-30

Revised date: 2024-01-05

Online published: 2025-02-13

唐依梦 , 刘扬 , 侯亚梅 . 乌兰木伦遗址非完整骨骼成因的实验考古学[J]. 人类学学报, 2025 , 44(01) : 42 -54 . DOI: 10.16359/j.1000-3193/AAS.2024.0032

Animal skeletons serve as valuable artifacts and crucial research targets in Paleolithic sites. Nevertheless, fragmented animal bones, especially those with species difficult to identify, have yet to receive adequate attention. The Wulanmulun site, a Middle Paleolithic site situated on the banks of the Wulanmulun River in Kangbashi New District, Ordos City, Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region, dates back to 65 kaBP ~ 50 kaBP. Since its discovery and excavation in 2010, a substantial number of stone artifacts and animal fossils have been unearthed. Currently, in-depth investigations have been carried out regarding lithic artifacts, zooarchaeology, and taphonomy at this site. Hence, we will concentrate on the abundant previously unstudied incomplete skeletons and explore their formation processes to uncover their associations with human behavior and natural burial.

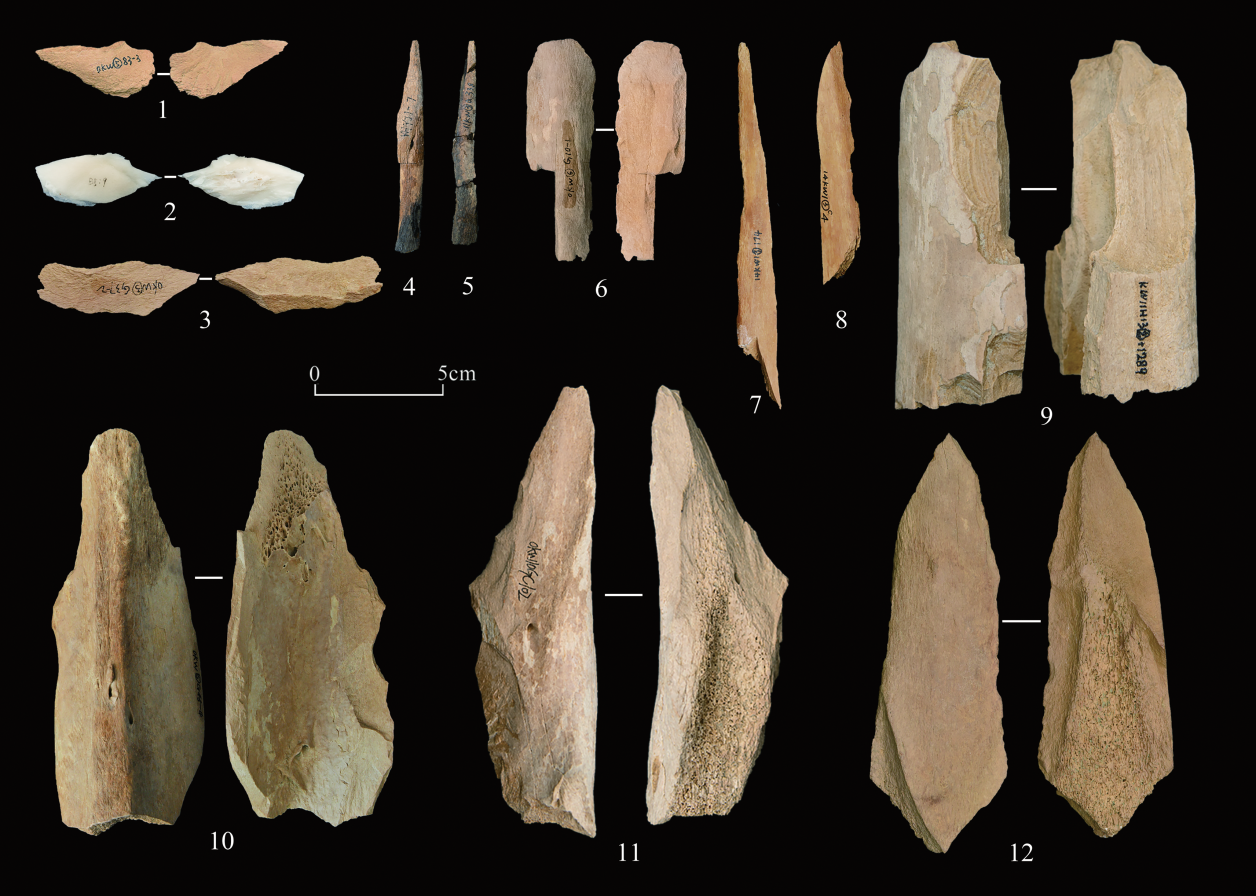

This paper centers on the 57,858 incomplete animal bone fossils excavated from the Wulanmulun site between 2010 and 2014, with the aim of probing into the formative factors of incomplete skeletal remains at the site. By means of quantitative analysis, experimental archaeology, and comparative analysis, we scrutinize the quantity and morphology of incomplete skeletal remains in an endeavor to elucidate the cultural traits and behavioral patterns of ancient humans. The findings suggest that: Firstly, the copious small-sized burned bones were presumably utilized as fuel instead of being the byproducts of roasting meat. Secondly, bone flakes, bone tools, and bone artifacts signify the activities of ancient humans in percussing and retouching bones, which differ from mere smashing for procuring food. Thirdly, through comparative analysis, it is deduced that marrow extraction and bone tool manufacturing coexisted at the Wulanmulun site, and the scarcity of 5 - 10 cm sized incomplete bones is correlated with the bone tool production activities of ancient humans. Fourthly, trampling experiments have verified that the fragmentation of bones caused by human and animal trampling is negligible and does not give rise to a large quantity of incomplete bones.

Consequently, this study implies that the formation of a large number of incomplete bones at the Wulanmulun site is intimately tied to ancient human activities such as marrow extraction, bone tool manufacturing, and bone burning. The Wulanmulun site comprehensively mirrors the cognitive level and utilization of animal bone resources by ancient humans, who not only harnessed meat resources but also exploited bone resources for marrow consumption, bone tool production, and fuel, exhibiting an efficient resource utilization strategy.

| [1] | 张双权. 旧石器遗址动物骨骼表面非人工痕迹研究及其考古学意义[J]. 第四纪研究, 2014, 34(1): 131-140 |

| [2] | Outram AK. A new approach to identifying bone marrow and grease exploitation: why the “indeterminate” fragments should not be ignored[J]. Journal of Archaeological Science, 2001, 28(4): 401-410 |

| [3] | Pickering TR, Marean CW, Dom??nguez-Rodrigo M. Importance of limb bone shaft fragments in zooarchaeology: a response to “On in situ attrition and vertebrate body part profiles”(2002), by MC Stiner[J]. Journal of Archaeological Science, 2003, 30(11): 1469-1482 |

| [4] | Gabucio MJ, Cáceres I, Rosell J, et al. From small bone fragments to Neanderthal activity areas: the case of Level O of the Abric Romaní (Capellades, Barcelona, Spain)[J]. Quaternary International, 2014, 330: 36-51 |

| [5] | Zhang JF, Hou YM, Guo YJ, et al. Radiocarbon and luminescence dating of the Wulanmulun site in Ordos, and its implication for the chronology of Paleolithic sites in China[J]. Quaternary Geochronology, 2022, 72: 1-10 |

| [6] | Rui X, Zhang JF, Hou YM, et al. Feldspar multi-elevated-temperature post-IR IRSL dating of the Wulanmulun Paleolithic site and its implication[J]. Quaternary Geochronology, 2015, 30: 438-444 |

| [7] | 刘扬, 侯亚梅, 杨泽蒙, 等. 鄂尔多斯乌兰木伦旧石器时代遗址埋藏学研究[J]. 考古, 2018, 1: 79-87 |

| [8] | Zhang LM, Griggo C, Dong W, et al. Preliminary taphonomic analyses on the mammalian remains from Wulanmulun Paleolithic site, Nei Mongol, China[J]. Quaternary International, 2016, 400: 158-165 |

| [9] | Costamagno S, Thery-Parisot I, Brugal JP, et al. Taphonomic consequences of the use of bones as fuel: experimental data and archaeological applications[A]. In: O’Connor T(Eds). Biosphere to lithosphere: new studies in vertebrate taphonomy[C]. Oxford: Oxbow, 2005, 51-62 |

| [10] | Marquer L, Otto T, Nespoulet R, et al. A new approach to study the fuel used in hearths by hunter-gatherers at the Upper Palaeolithic site of Abri Pataud (Dordogne, France)[J]. Journal of Archaeological Science, 2010, 37(11): 2735-2746 |

| [11] | Mentzer SM. Bone as a fuel source: the effects of initial fragment size distribution[A]. In: The?ry-Parisot I, Costamagno S, Henry A(Eds). Gestion des combustibles au Paleolithique et au Mesolithique: nouveaux outiles, nouvelles interpretations[C]. Oxford: Archaeopress, 2009, 53-64 |

| [12] | 张双权, 宋艳花, 张乐, 等. 柿子滩遗址第9地点出土的动物烧骨[J]. 人类学学报, 2019, 38(4): 598-612 |

| [13] | Cain CR. Using burned animal bone to look at Middle Stone Age occupation and behavior[J]. Journal of Archaeological Science, 2005, 32(6): 873-884 |

| [14] | Théry-Parisot I. économie du combustible et paléoécologie en contexte glaciaire et périglaciaire: paléolithique moyen et supérieur du sud de la France (anthracologie, expérimentation, haptonomie)[D]. Paris:Paris 1, 1998 |

| [15] | Bordes JG, Lenoble A. Caminade (Sarlat, Dordogne)[J]. Document final de synthèse de fouille programmée, Service régional de l’archéologie d’Aquitaine, 2001 |

| [16] | Yravedra J, Uzquiano P. Burnt bone assemblages from El Esquilleu cave (Cantabria, Northern Spain): deliberate use for fuel or systematic disposal of organic waste?[J]. Quaternary Science Reviews, 2013, 68: 175-190 |

| [17] | Théry-Parisot I, Costamagno S, Brugal JP, et al. The use of bone as fuel during the Palaeolithic, experimental study of bone combustible properties[A]. In: Mulville J, Outram AK(Eds). The Zooarchaeology of Fats, Oils, Milk and Dairying[C]. Oxford: Oxbow, 2005, 50-59 |

| [18] | 王志浩, 侯亚梅, 杨泽蒙, 等. 内蒙古鄂尔多斯市乌兰木伦旧石器时代中期遗址[J]. 考古, 2012, 7: 3-13 |

| [19] | 侯亚梅, 王志浩, 杨泽蒙, 等. 内蒙古鄂尔多斯乌兰木伦遗址2010年1期试掘及其意义[J]. 第四纪研究, 2012, 32(2): 178-187 |

| [20] | Dong W, Hou YM, Yang ZM, et al. Late Pleistocene mammalian fauna from Wulanmulan Paleolithic Site, Nei Mongol, China[J]. Quaternary International, 2014, 347: 139-147 |

| [21] | 龙凤骧. 马鞍山遗址出土碎骨表面痕迹分析[J]. 人类学学报, 1992, 3: 216-229 |

| [22] | Villa P, Mahieu E. Breakage patterns of human long bones[J]. Journal of Human Evolution, 1991, 21(1): 27-48 |

| [23] | 张双权. 河南许昌灵井动物群的埋藏学研究[D]. 北京: 中国科学院研究生院, 2009 |

| [24] | Capaldo SD, Blumenschine RJ. A quantitative diagnosis of notches made by hammerstone percussion and carnivore gnawing on bovid long bones[J]. American Antiquity, 1994, 59(4): 724-748 |

| [25] | Binford LR. Nunamiut Ethnoarchaeology[M]. New York: Academic Press, 1978 |

| [26] | 张俊山. 峙峪遗址碎骨的研究[J]. 人类学学报, 1991, 10(4): 333-345 |

| [27] | Binford LR. Bones: Ancient men and modern myths[M]. New York: Academic Press, 1981 |

| [28] | Pickering TR, Egeland CP. Experimental patterns of hammerstone percussion damage on bones: implications for inferences of carcass processing by humans[J]. Journal of Archaeological Science, 2006, 33(4): 459-469 |

| [29] | 刘扬, 侯亚梅, 杨泽蒙. 鄂尔多斯乌兰木伦遗址石制品拼合研究及其对遗址成因的指示意义[J]. 人类学学报, 2015, 34(1): 41-54 |

| [30] | 刘扬, 侯亚梅, 包蕾. 鄂尔多斯乌兰木伦遗址石器工业及其文化意义[J]. 考古学报, 2022, 4: 423-440 |

| [31] | 刘扬, 侯亚梅, 杨泽蒙, 等. 试论鄂尔多斯乌兰木伦遗址第1地点的性质和功能[J]. 北方文物, 2018, 3: 34-40 |

| [32] | Backwell L, d’Errico F. Early hominid bone tools from Drimolen, South Africa[J]. Journal of Archaeological Science, 2008, 35: 2880-2894 |

| [33] | Backwell L, d’Errico F. The first use of bone tools: a reappraisal of the evidence from Olduvai Gorge, Tanzania[J]. Palaeontology Africana, 2004, 40: 95-158 |

| [34] | 张双权, 李占扬, 张乐, 等. 河南灵井许昌人遗址动物骨骼表面人工改造痕迹[J]. 人类学学报, 2011, 30(3): 313-326 |

| [35] | 李超荣, 冯兴无, 郁金城, 等. 王府井东方广场遗址骨制品研究[J]. 人类学学报, 2004, 23(1): 13-33 |

| [36] | 张乐. 旧石器时代古人类敲骨取髓行为的确认:以马鞍山遗址为例[J]. 第四纪研究, 2014, 34(1): 141-148 |

/

| 〈 |

|

〉 |