主管:中国科学院

主办:中国科学院古脊椎动物与古人类研究所

出版:科学出版社

主办:中国科学院古脊椎动物与古人类研究所

出版:科学出版社

人类学学报 ›› 2025, Vol. 44 ›› Issue (01): 132-164.doi: 10.16359/j.1000-3193/AAS.2022.0044cstr: 32091.14.j.1000-3193/AAS.2022.0044

所属专题: 英文专辑

收稿日期:2021-06-01

修回日期:2021-11-22

出版日期:2025-02-15

发布日期:2025-02-13

Received:2021-06-01

Revised:2021-11-22

Online:2025-02-15

Published:2025-02-13

About author:Robin Dennell, Ph.D. Professor. E-mail: R.W.Dennell@exeter.ac.uk

摘要:

扩散(dispersals)、殖民(colonisation)、移居(immigration)、人口同化(assimilation)或取代(replacement)是东亚旧石器考古的基本主题。其中的一些主题,可以在生物地理学的框架内进行研究,主要通过研究古人类对气候和环境变化的响应,来阐释古人类种属在空间和时间上的变化及背后的原因。古人类(hominins)[尤其是智人(humans)]的行为受到技术、社会和认知发展等因素的影响,因此,在研究扩散时,生物地理学模型也必须包含对这些因素的思考。对于智人在东亚扩散至雨林,跨越海洋到达离岸岛屿,甚至到达北极和青藏高原最高地区的研究来说,这些因素尤为重要。以上述思考为基础,本文提出了一个研究古人类和智人在东亚扩散的方法论框架,该框架以生物地理学框架为基础,同时结合了古人类适应性和行为变化的因素。

中图分类号:

Robin DENNELL. 旧石器时代古人类和智人在东亚的扩散[J]. 人类学学报, 2025, 44(01): 132-164.

Robin DENNELL. Hominin and human dispersals in palaeolithic East Asia[J]. Acta Anthropologica Sinica, 2025, 44(01): 132-164.

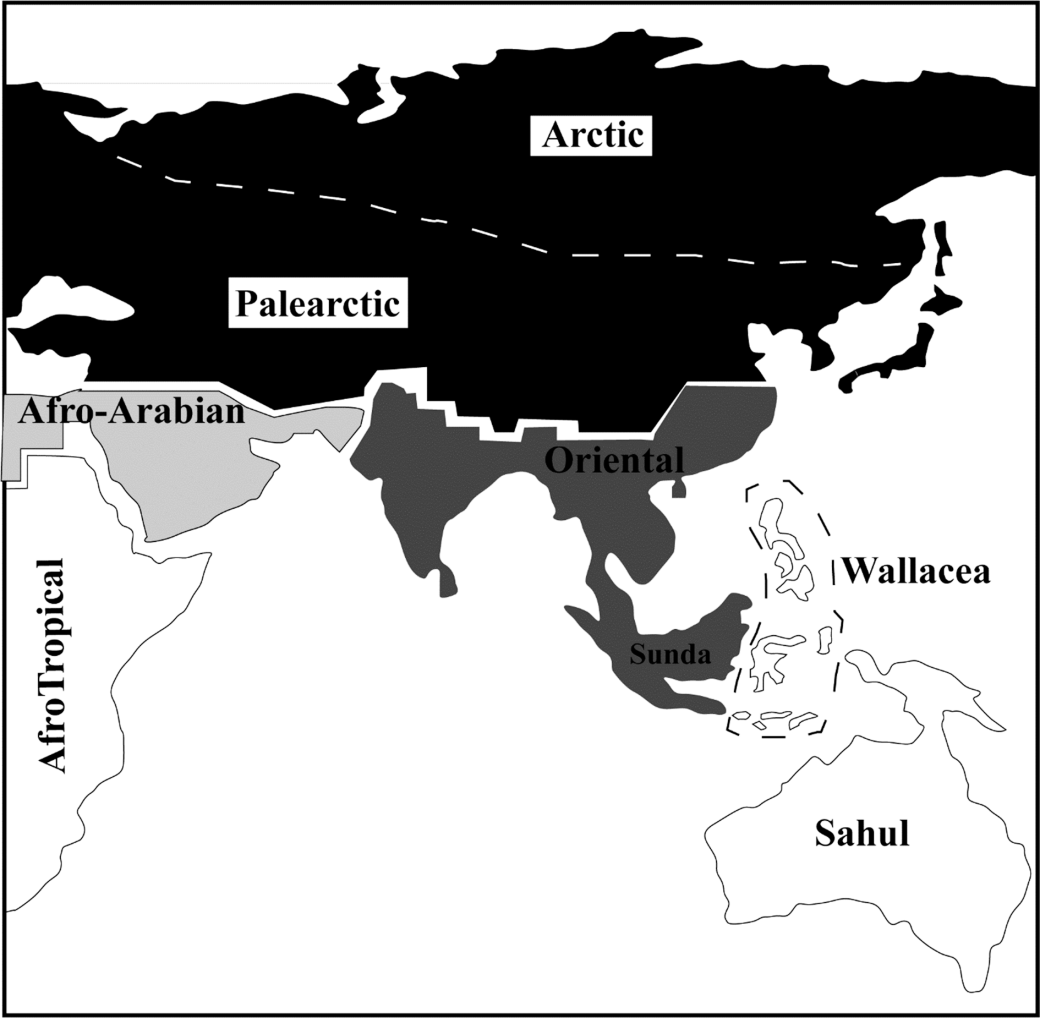

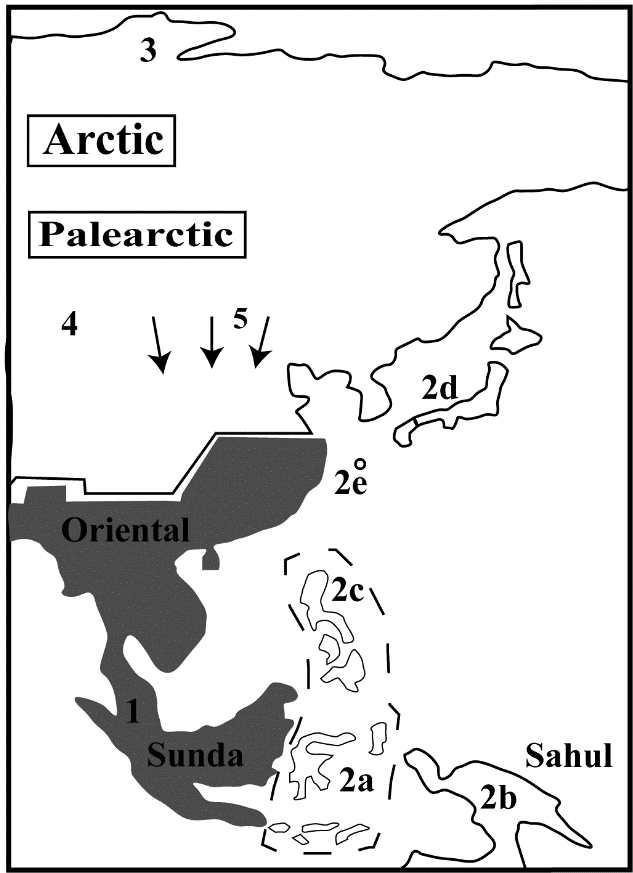

Fig.1 Biogeographic realms and sub-realms of Asia The two sub-realms are the Arctic (as a sub-realm of the Palearctic) and Wallacea (as a sub-Realm of the Oriental Realm). Sea-levels are shown at 40-60 m below present levels for the Arabian-Persian Gulf, Sunda and Sahul. Redrawn and modified from the Fig.1 of reference [17]

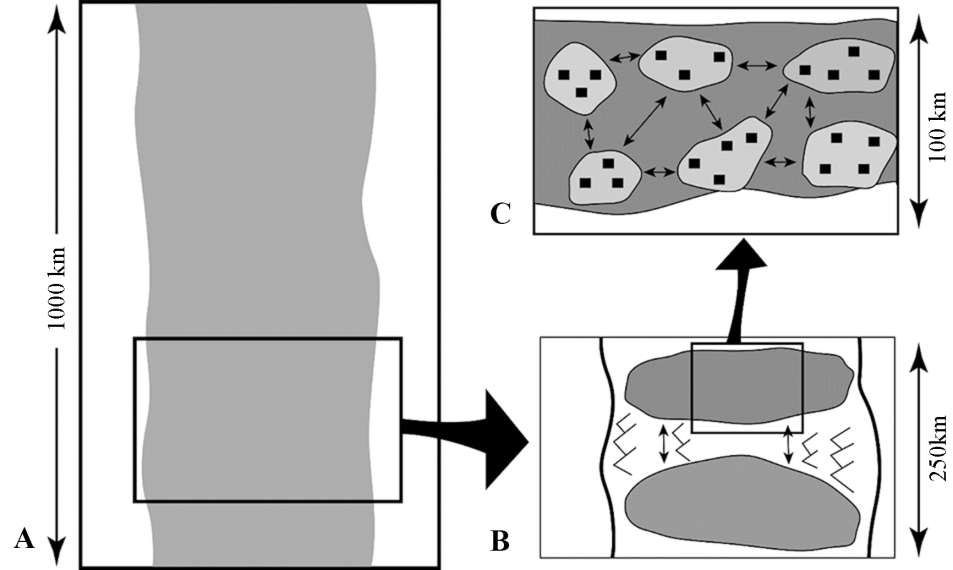

Fig.2 Range and metapopulation distribution Within the total range of a species (A), there would have been spatially separated but inter-dependent populations (B). At a smaller scale, each metapopulation would have comprised further sub-sets of subsistence groups (C) whose membership was largely constant from year to year, and whose monthly and annual movements were usually over the same territory. These groups would form networks within which mates, resources, and information could be exchanged. The distances shown in these figures is intended only to show relative differences in the scale of analysis

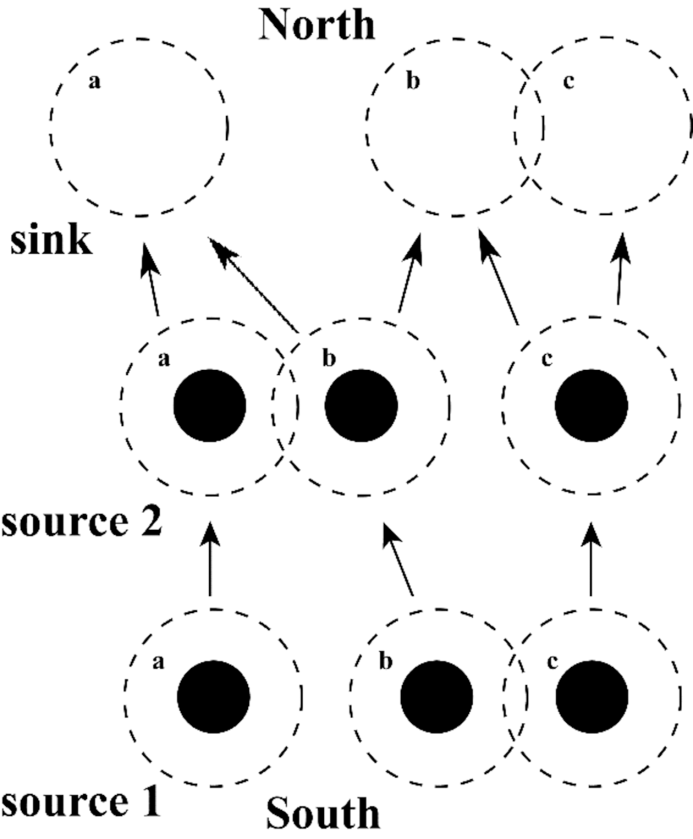

Fig.3 Source and sink populations Source and sink populations: here, the bottom row indicates three metapopulations, or palaeodemes, in glacial refugia at the southern limit of the species’ range. These are source populations that provide the basis for later expansion. The solid circles denote metapopulations during cold periods when populations contract into refugia; the dashed circles indicate interglacial or interstadial conditions when expansion from them is possible. Each is separated in glacial conditions, but in interglacial conditions, metapopulations b and c overlap. The middle row indicates how each expands in interglacial times and becomes a source population: here, metapopulations 2a and 2b overlap, but 2c (derived originally from demes b and c) remains isolated. The top row indicates the maximum expansion during an interglacial; here, deme 3a (derived from demes 2a and 2b) is isolated, but demes 3b and 3c overlap, although each has a different ancestry. At the northern edge of the species range, the metapopulations are sink populations in that they require recruitment from source populations to remain viable

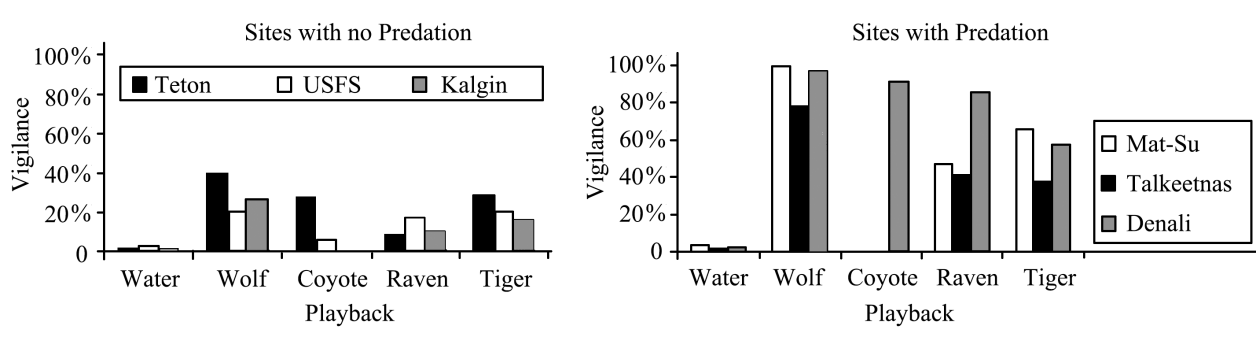

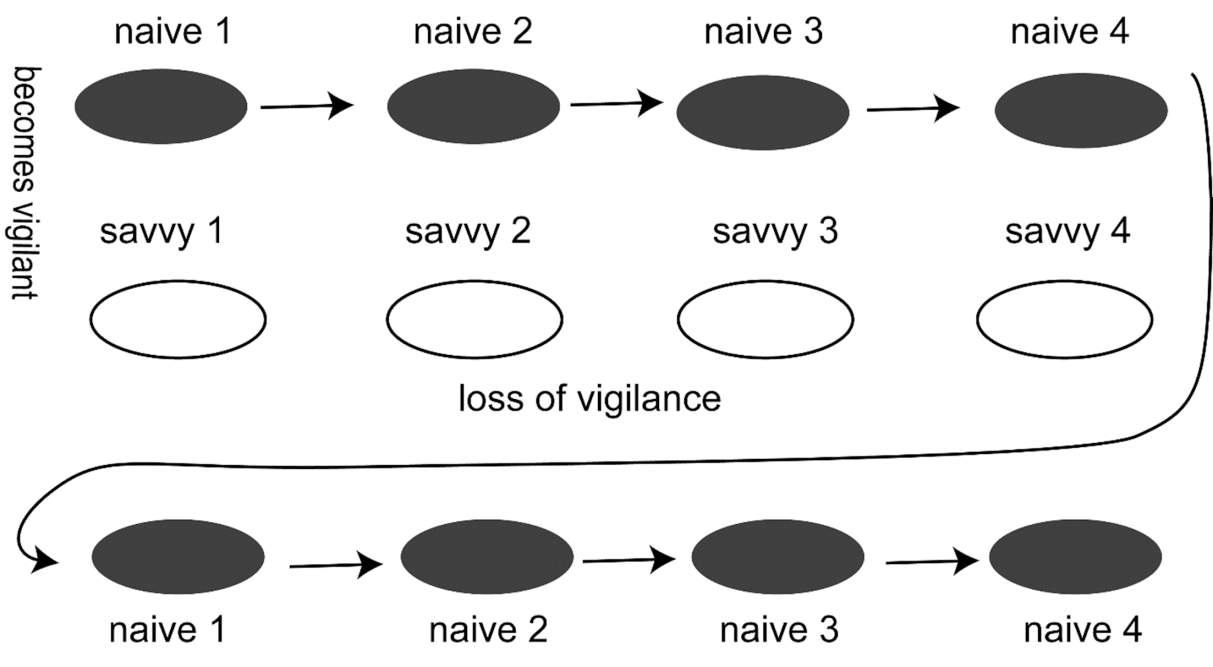

Fig.4 Responses of moose to auditory predator cues among predator-naïve and -savvy herds Moose in areas where there was no predation were far less vigilant in their responses to the sounds of wolf, coyote and ravens (notable scavengers of predator kills) and even tiger than those in areas of predation. The sound of running water was used as a control in both groups[67]

Fig.5 Hominin dispersals in regions of predator-naïve and predator-savvy faunas In this model, a hominin group targets four predator-naïve faunas in succession. Each fauna responds by becoming predator-savvy. However, over time, they lose vigilance and revert to being predator-naïve. At that point, the hominin group has the option of either moving to a new area with a naïve-fauna, or returning to one where a savvy fauna had lost its vigilance. This type of dispersal may be applicable to H. erectus in continental Eurasia, to later hominins recolonizing an area vacated during a climatic downturn, and to late Pleistocene populations of H. sapiens when colonising regions such as Australia, island Southeast Asia, Japan and the Americas.

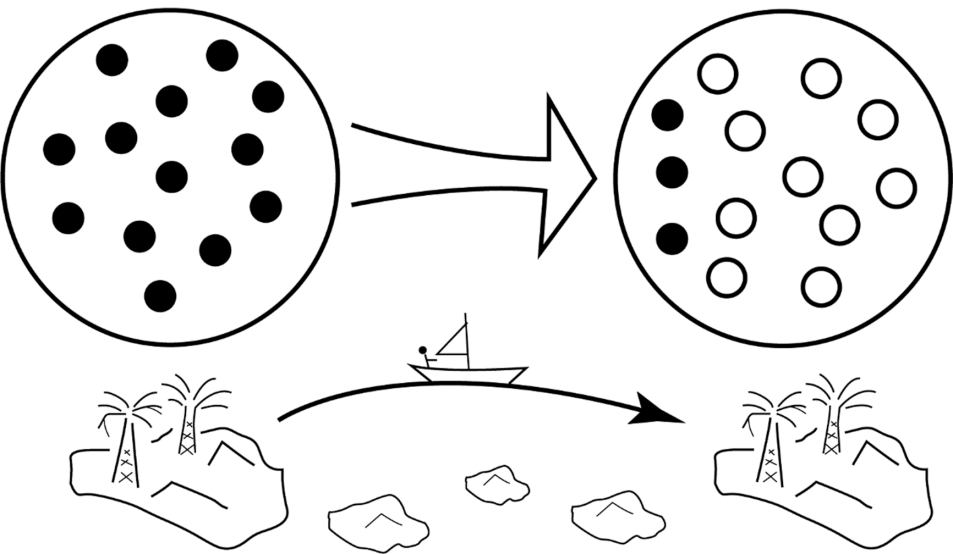

Fig.6 Jump dispersal This diagram shows bold colonization by jump dispersal. Here, some groups (A, black circles) at the edge of an island metapopulation take the risk of jumping past a series of unproductive islands to find a better island (B) than their present location. Although the risk of failure is high, success means that a new region can be colonized by descendant groups (white circles). Jump dispersals can also happen on land, as when people “jump” from one oasis to another when crossing a desert.

| Continental East Asia | South China and Southeast Asia | |

|---|---|---|

| Biogeographic realm | Palearctic | Oriental |

| Climate | cool/cold, dry; sub-freezing winters | warm, wet; warm winters |

| Rainfall | largely winter | monsoonal; summer |

| Plant foods | scarce and seasonal | abundant year round |

| Animal foods | herd and migratory (e.g. horse, gazelle) | small groups or solitary; localised |

| Subsistence | highly mobile if dependent on terrestrial resources | mobile but usually with small annual territories |

| Population size and density | small, dispersed if dependent on terrestrial resources; possibly larger if dependent on coastal resources | usually larger and less dispersed |

| Level of risk | high | lower |

| Type of clothing | clothing - hide/fur | optional, or plant based |

| Regional occupation records | often discontinuous | more likely continuous |

| Raw materials | sometimes obtained over large distances | usually local |

| First appearance of H. sapiens | 45 - 40 kaBP | Possibly as early as 80 - 100 kaBP |

Tab.1 Summary of differences between the Palearctic and Oriental realms of China and neighbouring regions

| Continental East Asia | South China and Southeast Asia | |

|---|---|---|

| Biogeographic realm | Palearctic | Oriental |

| Climate | cool/cold, dry; sub-freezing winters | warm, wet; warm winters |

| Rainfall | largely winter | monsoonal; summer |

| Plant foods | scarce and seasonal | abundant year round |

| Animal foods | herd and migratory (e.g. horse, gazelle) | small groups or solitary; localised |

| Subsistence | highly mobile if dependent on terrestrial resources | mobile but usually with small annual territories |

| Population size and density | small, dispersed if dependent on terrestrial resources; possibly larger if dependent on coastal resources | usually larger and less dispersed |

| Level of risk | high | lower |

| Type of clothing | clothing - hide/fur | optional, or plant based |

| Regional occupation records | often discontinuous | more likely continuous |

| Raw materials | sometimes obtained over large distances | usually local |

| First appearance of H. sapiens | 45 - 40 kaBP | Possibly as early as 80 - 100 kaBP |

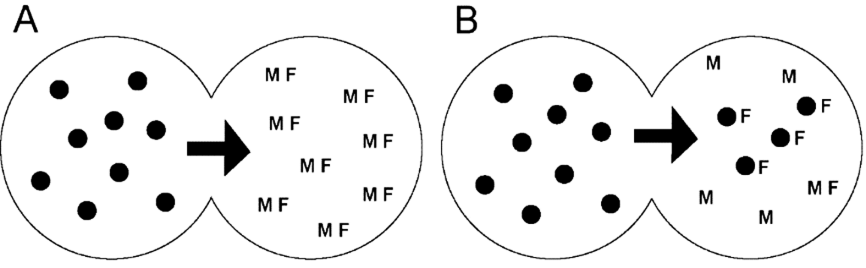

Fig. 7 Colonisation by assimilation In this scenario, part of a metapopulation (A; black circles) begins to invade an area occupied by a different type of hominin, shown as MF, with M = males and F = females. The invasive metapopulation then proceeds to assimilate the females of reproductive age (B), thus degrading the previous viability of the indigenous population. This type of scenario is indicated by evidence of gene flow from Neanderthals and Denisovans into Homo sapiens in Siberia and may also help explain the evidence for hybridization in the East Asian skeletal evidence.

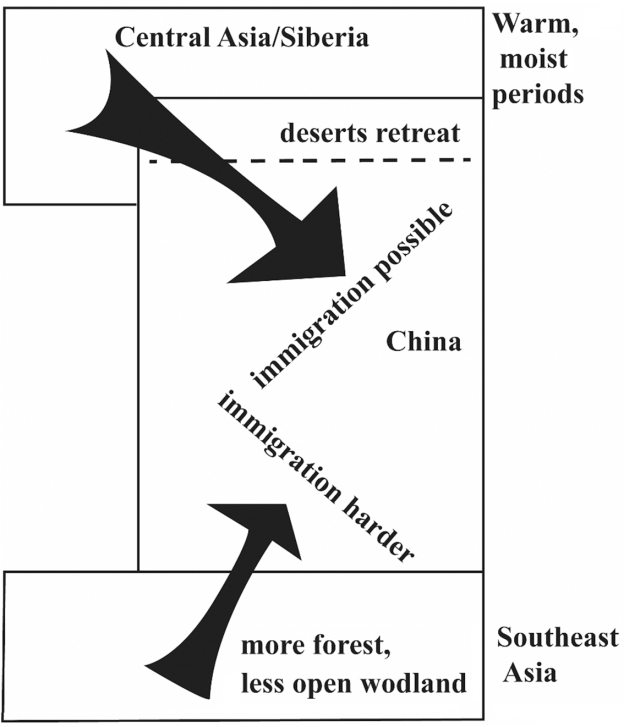

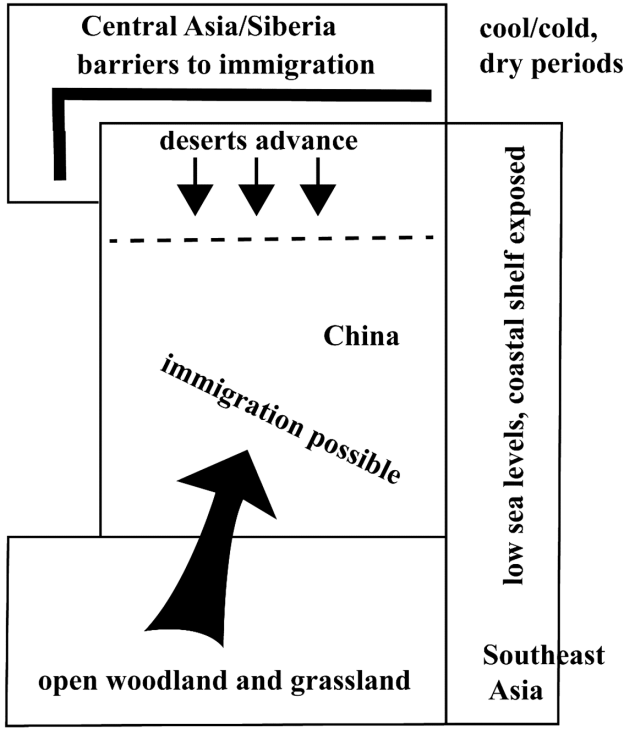

Fig.8 Model of immigration into China in warm periods In warm, moist periods, the desert boundary retreated and immigration into north China was possible from regions to the north and west. In south China, immigration from southeast Asia might have been more difficult because of the expansion of rain forest. Source: the author

Fig.9 Model of immigration into China in cold periods In cold, dry periods, the desert boundary shifted southwards in north China, and immigration from regions to the north and west would have become more difficult. On the other hand, the contraction of rain forest and expansion of open woodland and grassland in south China would have facilitated immigration from southwest Asia. In addition, the fall in sea levels exposed more land and opened up possibilities for colonisation. Source: the author

Fig.10 Human dispersals in East Asia after 70 kaBP There were 5 major dispersal events in East Asia by H. sapiens after 70 kaBP: 1. Dispersal in the Oriental Realm into rain forest in Sumatra (Lida Ajer) and Borneo (Niah cave) and possibly South China (Xiaodong); 2. A series of jump dispersals to off-shore islands: 2a. Wallacea; 2b, 2b. Sahul; 2c. the Philippines; 2d. PalaeoHonshu (the conjoined islands of Kyusho, Honshu and Shikoku); 2e. Okinawa and the other Ryuku islands; 3. The high Arctic (Yana, Sopochnaya Karga); 4. The Tibetan Plateau above 4000 m in altitude; 5. Dispersals into North China from Mongolia and South Siberia (SDG 1 and later: the microblade tradition) by cold-adapted groups. These dispersal events were in addition to the previous pattern of ebb-and-flow in the Loess Plateau by communities whose source populations were further south

| [1] | Dennell RW. Where evolutionary biology meets history: ethno-nationalism and modern human origins in East Asia[A]. In: Schwartz JP (Ed.). Rethinking Human Evolution[C]. London: MIT Press, 2018, 229-250 |

| [2] | Osborn HF. The Age of Mammals in Europe, Asia and North America[M]. New York: The Macmillan Company, 1910, 1-635 |

| [3] | Osborne HF. Men of the Old Stone Age[M]. New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1918 |

| [4] | Matthew WD. Climate and evolution[M]. New York: Academy of Sciences, 1915, 171-318 |

| [5] | Bowler P. Theories of Human Evolution:A Century of Debate, 1844-1944[M]. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1986, 1-324 |

| [6] | Black D. Asia and the dispersal of primates[J]. Acta Geologica Sinica (English edition), 1925, 4(2): 136-196 |

| [7] | Black D. The Croonian Lecture—On the discovery, morphology, and environment of Sinanthropus pekinensis[J]. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. Series B, 1934, 223(494-508): 57-120 |

| [8] | Licent EP, de Chardin T. Le paléolithique de la Chine[J]. L’Anthropologie, 1925, 25, 201-234 |

| [9] | Boule M, Breuil H, Licent E, et al. Le Paléolithique de la Chine[M]. Paris: Archives de L’Institut de Paléontologie Humanie, 1928, 4, 1-138 |

| [10] | Dennell RW. From Sangiran to Olduvai, 1937-1960:The quest for “centres” of Hominid origins in Asia and Africa[A]. In: Corbey R, Roebroeks W (Eds.). Studying Human Origins: Disciplinary History and Epistemology[C]. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press, 2001, 45-66 |

| [11] | Dennell RW. The Far West from the Far East: decolonisation and human origins in East Asia:the legacy of 1937 and 1948[A]. In: Porr M, Matthews J (Eds.). Interrogating Human Origins[C]. Abingdon: Routledge, 2019, 211-238 |

| [12] | Dennell RW. The Palaeolithic Settlement of Asia[M]. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2008, 1-572 |

| [13] | Dennell RW. From Arabia to the Pacific: How our Species Colonised Asia[M]. Abingdon: Routledge, 2020, 1-386 |

| [14] | Burke A, Kageyama M, Latombe G. et al. Risky business: The impact of climate and climate variability on human population dynamics in Western Europe during the Last Glacial Maximum[J]. Quaternary Science Reviews, 2017, 164: 217-229 |

| [15] | Norton CJ, Jin CZ, Wang Y, et al. Rethinking the Palearctic-Oriental biogeographic boundary[A]. In: Norton CJ, Braun DR (Eds.). Asian Paleoanthropology from Africa to China and Beyond[C]. New York: Springer Science+Business Media, 2010, 81-100 |

| [16] | Tong HW. Occurrences of warm-adapted mammals in North China over the Quaternary period and their paleo-environmental significance[J]. Science in China Series D: Earth Sciences, 2007, 50(9): 1327-1340 |

| [17] |

Holt BG, Lessard JP, Borregaard MK, et al. An update of Wallace’s zoogeographic regions of the world[J]. Science, 2013, 339(6115): 74-78

doi: 10.1126/science.1228282 pmid: 23258408 |

| [18] | Scerri ML, Thomas MG, Manica A, et al. Did our species evolve in subdivided populations across Africa, and why does it matter?[J]. Trends in ecology & evolution, 2018, 33(8): 582-594 |

| [19] | Howell FC. Thoughts on the study and interpretation of the human fossil record[A]. In: Meikle WE, Howell FC, Jablonski NG (Eds.). Contemporary Issues in Human Evolution[C]. San Francisco: California Academy of Sciences Memoir, 1996, 1-45 |

| [20] | Howell FC. Paleo-demes, species clades, and extinctions in the Pleistocene hominin record[J]. Journal of Anthropological Research, 1999, 55(2): 191-243 |

| [21] | Martinon-Torres M, Xing S, Liu W, et al. A “source and sink” model for East Asia? Preliminary approach through the dental evidence[J]. Comptes Rendus Palevol, 2018, 17(1-2): 33-43 |

| [22] |

Dennell RW. Dispersal and colonisation, long and short chronologies: how continuous is the Early Pleistocene record for hominids outside East Africa?[J]. Journal of Human Evolution, 2003, 45(6): 421-440.

pmid: 14643672 |

| [23] | Dennell RW. Hominid dispersals and Asian biogeography during the Lower and Early Middle Pleistocene, ca. 2.0-0.5 Mya[J]. Asian Perspectives, 2004, 43 (2): 205-226 |

| [24] | Ding ZL, Derbyshire E, Yang SL, et al. Stacked 2.6-Ma grain size record from the Chinese loess based on five sections and correlation with the deep-sea δ18O record[J]. Paleoceanography, 2002, 17(3): 5-1-5-21 |

| [25] | Guo ZT, Liu TS, Fedoroff N, et al. Climate extremes in loess in China coupled with the strength of deep-water formation in the North Atlantic[J]. Global and Planetary Change, 1998, 18(3-4): 113-128 |

| [26] | Zhu ZY, Dennell RW, Huang WW, et al. New dating of the Homo erectus cranium from Lantian (Gongwangling), China[J]. Journal of Human Evolution, 2015, 78: 144-157 |

| [27] | Takahashi K, Wei G, Uno H, et al. AMS 14C chronology of the world’s southernmost woolly mammoth (Mammuthus primigenius Blum.)[J]. Quaternary Science Reviews, 2007, 26(7-8): 954-957 |

| [28] | Zhu ZY, Dennell R., Huang WW, et al. Hominin occupation of the Chinese Loess Plateau since about 2.1 million years ago[J]. Nature, 2018, 559(7715): 608-612 |

| [29] | Lu HY, Zhang HY, Wang SJ, et al. Multiphase timing of hominin occupations and the paleoenvironment in Luonan Basin, Central China[J]. Quaternary Research, 2011, 76(1): 142-147 |

| [30] |

Lu HY, Sun XF, Wang SJ, et al. Ages for hominin occupation in Lushi Basin, middle of South Luo River, central China[J]. Journal of Human Evolution, 2011, 60(5): 612-617

doi: 10.1016/j.jhevol.2010.12.009 pmid: 21353287 |

| [31] | Sun XF, Lu HY, Wang SJ, et al. Hominin distribution in glacial-interglacial environmental changes in the Qinling Mountains range, central China[J]. Quaternary Science Reviews, 2018, 198: 37-55 |

| [32] | Dennell RW, Martinón-Torres M, et al. A demographic history of Late Pleistocene China[J]. Quaternary International, 2020, 559: 4-13 |

| [33] | Dennell RW. The Nihewan Basin of North China in the Early Pleistocene: Continuous and flourishing, or discontinuous, infrequent and ephemeral occupation?[J]. Quaternary International, 2013, 295: 223-236 |

| [34] | Liu P, Deng CL, Li SH, et al. Magnetostratigraphic dating of the Huojiadi Paleolithic site in the Nihewan Basin, North China[J]. Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology, 2010, 298(3-4): 399-408 |

| [35] | Zhu RX, Potts R, Xie F, et al. New evidence on the earliest human presence at high northern latitudes in northeast Asia[J]. Nature, 2004, 431(7008): 559-562 |

| [36] |

Zhang XL, Ha BB, Wang SJ, et al. The earliest human occupation of the high-altitude Tibetan Plateau 40 thousand to 30 thousand years ago[J]. Science, 2018, 362(6418): 1049-1051

doi: 10.1126/science.aat8824 pmid: 30498126 |

| [37] | Zhang JF, Dennell RW. The last of Asia conquered by Homo sapiens: excavation reveals the earliest human colonization of the Tibetan Plateau[J]. Science, 2018, 362(6418): 992-993 |

| [38] | Parfitt S, Ashton NM, Lewis SG, et al. Early Pleistocene human occupation at the edge of the boreal zone in northwest Europe[J]. Nature, 2010, 466(7303): 229-233 |

| [39] | Pei SW, Li XL, Liu DC, et al. Preliminary study on the living environment of hominids at the Donggutuo site, Nihewan Basin[J]. Chinese Science Bulletin, 2009, 54(21): 3896-3904 |

| [40] | Hublin JJ, Roebroeks W. Ebb and flow or regional extinctions? On the character of Neandertal occupation of northern environments[J]. Comptes Rendus Palevol, 2009, 8(5): 503-509 |

| [41] | Tallavaara M, Luoto M, Korhonen N, et al. Human population dynamics in Europe over the Last Glacial Maximum[J]. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 2015, 112(27): 8232-8237 |

| [42] | Wang C, Lu H, Zhang J, et al. Prehistoric demographic fluctuations in China inferred from radiocarbon data and their linkage with climate change over the past 50,000 years[J]. Quaternary Science Reviews, 2014, 98: 45-59 |

| [43] | Dennell R. Hominins, deserts, and the colonisation and settlement of continental Asia[J]. Quaternary International, 2013, 300: 13-21 |

| [44] |

Li F, Petraglia M, Roberts P, et al. The northern dispersal of early modern humans in eastern Eurasia[J]. Science Bulletin, 2020, 65(20): 1699-1701

doi: 10.1016/j.scib.2020.06.026 pmid: 36659239 |

| [45] | Huang WW, Olsen JW, Reeves RW, et al. New discoveries of stone artefacts on the southern edge of the Tarim Basin, Xinjiang[J]. Acta Anthropologica Sinica, 1988, 7(4): 294-301 |

| [46] | Li KK, Qin XG, Yang XY, et al. Human activity during the late Pleistocene in the Lop Nur region, northwest China: Evidence from a buried stone artifact[J]. Science China Earth Sciences, 2018, 61(11): 1659-1668 |

| [47] | Han WX, Yu LP, Lai ZP, et al. The earliest well-dated archeological site in the hyper-arid Tarim Basin and its implications for prehistoric human migration and climatic change[J]. Quaternary Research, 2014, 82(1): 66-72 |

| [48] | Bacon AM, Duringer P, Westaway K, et al. Testing the savannah corridor hypothesis during MIS2: The Boh Dambang hyena site in southern Cambodia[J]. Quaternary International, 2018, 464: 417-439 |

| [49] | Dennell R, Roebroeks W. An Asian perspective on early human dispersal from Africa[J]. Nature, 2005, 438(7071): 1099-1104 |

| [50] | Ding ZL, Derbyshire E, Yang SL, et al. Stepwise expansion of desert environment across northern China in the past 3.5 Ma and implications for monsoon evolution[J]. Earth and Planetary Science Letters, 2005, 237(1-2): 45-55 |

| [51] | Fang XM, Shi ZT, Yang SL, et al. Loess in the Tian Shan and its implications for the development of the Gurbantunggut Desert and drying of northern Xinjiang[J]. Chinese Science Bulletin, 2002, 47(16): 1381-1387 |

| [52] | Fang XM, Lye LQ, Yang SL, et al. Loess in Kunlun Mountains and its implications on desert development and Tibetan Plateau uplift in west China[J]. Science in China Series D: Earth Sciences, 2002, 45(4): 289-299 |

| [53] | Yang SL, Ding ZL. Winter-spring precipitation as the principal control on predominance of C3 plants in Central Asia over the past 1.77 Myr: Evidence from δ13C of loess organic matter in Tajikistan[J]. Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology, 2006, 235(4): 330-339 |

| [54] | Prokopenko AA, Williams DF, Kuzmin MI, et al. Muted climate variations in continental Siberia during the mid- Pleistocene epoch[J]. Nature, 2002, 418(6893): 65-68 |

| [55] | Hao QZ, Wang L, Oldfield F, et al. Extra-long interglacial in Northern Hemisphere during MISs 15-13 arising from limited extent of Arctic ice sheets in glacial MIS 14[J]. Scientific Reports, 2015, 5(1): 1-8 |

| [56] | Rightmire GP. Human evolution in the Middle Pleistocene: the role of Homo heidelbergensis[J]. Evolutionary Anthropology: Issues, News, and Reviews, 1998, 6(6): 218-227 |

| [57] | Groves CP. A bush not a ladder: speciation and replacement in human evolution[J]. Perspectives in Human Biology, 1994, 4: 1-11 |

| [58] |

Wu XZ, Athreya S. A description of the geological context, discrete traits, and linear morphometrics of the Middle Pleistocene hominin from Dali, Shaanxi Province, China[J]. American Journal of Physical Anthropology, 2013, 150(1): 141-157

doi: 10.1002/ajpa.22188 pmid: 23283667 |

| [59] | Bae CJ. The late Middle Pleistocene hominin fossil record of eastern Asia: synthesis and review[J]. American Journal of Physical Anthropology, 2010, 143(S51): 75-93 |

| [60] | Dennell R. Life without the Movius line: The structure of the east and Southeast Asian Early Palaeolithic[J]. Quaternary International, 2016, 400: 14-22 |

| [61] | Dennell RW, Martinón-Torres M, de Castro JMB. Hominin variability, climatic instability and population demography in Middle Pleistocene Europe[J]. Quaternary Science Reviews, 2011, 30(11-12): 1511-1524 |

| [62] | McDonald K, Martinón-Torres M, Dennell RW, et al. Discontinuity in the record for hominin occupation in south-western Europe: Implications for occupation of the middle latitudes of Europe[J]. Quaternary International, 2012, 271: 84-97 |

| [63] | Louys J, Turner A. Environment, preferred habitats and potential refugia for Pleistocene Homo in Southeast Asia[J]. Comptes Rendus Palevol, 2012, 11(2-3): 203-211 |

| [64] | Dennell RW. Pleistocene hominin dispersals, naïve faunas and social networks[A]. In: Boivin N, Crassard R, Petraglia M (Eds.). Human Dispersal and Species Movement from Prehistory to the Present[C]. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2017, 62-89 |

| [65] |

Berger J, Swenson JE, Persson IL. Recolonizing carnivores and naive prey: conservation lessons from Pleistocene extinctions[J]. Science, 2001, 291(5506): 1036-1039

pmid: 11161215 |

| [66] | Laundré JW, Hernández L, Altendorf KB. Wolves, elk, and bison: reestablishing the “landscape of fear” in Yellowstone National Park, USA[J]. Canadian Journal of Zoology, 2001, 79(8): 1401-1409 |

| [67] | Berger J, Stacey PB, Bellis L, et al. A mammalian predator-prey imbalance: grizzly bear and wolf extinction affect avian neotropical migrants[J]. Ecological Applications, 2001, 11(4): 947-960 |

| [68] | Mosimann JE, Martin PS. Simulating overkill by Paleoindians: did man hunt the giant mammals of the New World to extinction? Mathematical models show that the hypothesis is feasible[J]. American Scientist, 1975, 63(3): 304-313 |

| [69] |

Zhu RX, Potts R, Pan YX, et al. Early evidence of the genus Homo in East Asia[J]. Journal of human evolution, 2008, 55(6): 1075-1085

doi: 10.1016/j.jhevol.2008.08.005 pmid: 18842287 |

| [70] | Turner A. Large carnivores and earliest European hominids: changing determinants of resource availability during the Lower and Middle Pleistocene[J]. Journal of Human Evolution, 1992, 22(2): 109-126 |

| [71] | Turner A, Antón M. The giant hyaena, Pachycrocuta brevirostris (Mammalia, Carnivora, Hyaenidae) L’hyène géante, Pachycrocuta brevirostris (Mammalia, Carnivora, Hyaenidae)[J]. Geobios, 1996, 29: 455-446 |

| [72] | Madurell-Malapeira J, Alba DM, Espigares MP, et al. Were large carnivorans and great climatic shifts limiting factors for hominin dispersals? Evidence of the activity of Pachycrocuta brevirostris during the Mid-Pleistocene Revolution in the Vallparadís Section (Vallès-Penedès Basin, Iberian Peninsula)[J]. Quaternary International, 2017, 431: 42-52 |

| [73] | Palmqvist P, Martínez-Navarro B, Pérez-Claros JA, et al. The giant hyena Pachycrocuta brevirostris: modelling the bone-cracking behavior of an extinct carnivore[J]. Quaternary International, 2011, 243(1): 61-79 |

| [74] | Binford LR, Stone NM, Aigner JS, et al. Zhoukoudian: a closer look[J]. Current Anthropology, 1986, 27(5): 453-475 |

| [75] | Boaz NT, Ciochon RL, Xu QQ, et al. Large mammalian carnivores as a taphonomic factor in the bone accumulation at Zhoukoudian[J]. Acta Anthropol Sinica, 2000, 19(S): 224-234 |

| [76] | Boaz NT, Ciochon RL, Xu Q, et al. Mapping and taphonomic analysis of the Homo erectus loci at Locality 1 Zhoukoudian, China[J]. Journal of Human Evolution, 2004, 46(5): 519-549 |

| [77] | Kuhn SL, Stiner MC. What’s a mother to do? The division of labor among Neandertals and modern humans in Eurasia[J]. Current anthropology, 2006, 47(6): 953-981 |

| [78] | Shea JJ, Sisk ML. Complex projectile technology and Homo sapiens dispersal into western Eurasia[J]. PaleoAnthropology, 2010, 100-122 |

| [79] | Khatsenovich AM, Rybin EP, Gunchinsuren B, et al. New evidence for Paleolithic human behavior in Mongolia: the Kharganyn Gol 5 site[J]. Quaternary International, 2017, 442: 78-94 |

| [80] | Pavlov P, Svendsen JI, Indrelid S. Human presence in the European Arctic nearly 40,000 years ago[J]. Nature, 2001, 413(6851): 64-67 |

| [81] |

Slimak L, Svendsen JI, Mangerud J, et al. Late Mousterian persistence near the Arctic circle[J]. Science, 2011, 332(6031): 841-845

doi: 10.1126/science.1203866 pmid: 21566192 |

| [82] | Zwyns N, Roebroeks W, McPherron SP, et al. Comment on “Late Mousterian persistence near the Arctic Circle”[J]. Science, 2012, 335(6065): 167 |

| [83] |

Li F, Kuhn SL, Chen FY, et al. The easternmost middle paleolithic (Mousterian) from Jinsitai cave, north China[J]. Journal of Human Evolution, 2018, 114: 76-84

doi: S0047-2484(17)30303-2 pmid: 29447762 |

| [84] | Chen FH, Welker F, Shen CC, et al. A late middle Pleistocene Denisovan mandible from the Tibetan plateau[J]. Nature, 2019, 569(7756): 409-412 |

| [85] | Morwood MJ, O’Sullivan PB, Aziz F, et al. Fission-track ages of stone tools and fossils on the east Indonesian island of Flores[J]. Nature, 1998, 392(6672): 173-176 |

| [86] | Brumm A, Jensen GM, van den Bergh GD, et al. Hominins on Flores, Indonesia, by one million years ago[J]. Nature, 2010, 464(7289): 748-752 |

| [87] | Bednarik RG. Seafaring in the Pleistocene[J]. Cambridge Archaeological Journal, 2003, 13(1): 41-66 |

| [88] | Howitt-Marshall D, Runnels C. Middle Pleistocene sea-crossings in the eastern Mediterranean?[J]. Journal of Anthropological Archaeology, 2016, 42: 140-153 |

| [89] | Leppard TP, Runnels C. Maritime hominin dispersals in the Pleistocene: advancing the debate[J]. Antiquity, 2017, 91: 510-519 |

| [90] | Strasser TF, Runnels C, Wegmann K, et al. Dating Palaeolithic sites in southwestern Crete, Greece[J]. Journal of Quaternary Science, 2011, 26(5): 553-560 |

| [91] | Strasser TF, Runnels C, Vita-Finzi C. A possible Palaeolithic hand axe from Cyprus[J]. Antiquity Project Gallery, 2016, 90: 350 |

| [92] | Flynn JJ, Wyss AR. Recent advances in South American mammalian paleontology[J]. Trends in Ecology & Evolution, 1998, 13: 449-454 |

| [93] | de Queiroz A. The resurrection of oceanic dispersal in historical biogeography[J]. Trends in ecology & evolution, 2005, 20(2): 68-73 |

| [94] | Ali JR, Huber M. Mammalian biodiversity on Madagascar controlled by ocean currents[J]. Nature, 2010, 463(7281): 653-656 |

| [95] | Simpson GG. Mammals and land bridges[J]. Journal of the Washington Academy of Sciences, 1940, 30(4): 137-163 |

| [96] | Leppard TP. Passive dispersal versus strategic dispersal in island colonization by hominins[J]. Current Anthropology, 2015, 56(4): 590-595 |

| [97] |

Ruxton GD, Wilkinson DM. Population trajectories for accidental versus planned colonisation of islands[J]. Journal of Human Evolution, 2012, 63(3): 507-511

doi: 10.1016/j.jhevol.2012.05.013 pmid: 22748511 |

| [98] | Dennell RW, Louys J, O’Regan HJ, et al. The origins and persistence of Homo floresiensis on Flores: Biogeographical and ecological perspectives[J]. Quaternary Science Reviews, 2014, 96: 98-107 |

| [99] | Ingicco T, van den Bergh GD, Jago-On C, et al. Earliest known hominin activity in the Philippines by 709 thousand years ago[J]. Nature, 2018, 557(7704): 233-237 |

| [100] | Smith JMB. Did early hominids cross sea gaps on natural rafts?[A] In: Metcalf I, Smith J, Davidson I, Morwood MJ (Eds.). Faunal and Floral Migrations and Evolution in SE Asia-Australasia[C]. The Netherlands: Swets and Zeitlinger, 2001, 409-416 |

| [101] | Ihara Y, Ikeya K, Nobayashi A, et al. A demographic test of accidental versus intentional island colonization by Pleistocene humans[J]. Journal of Human Evolution, 2020, 145: 102839 |

| [102] | Van den Bergh GD, Li B, Brumm A, et al. Earliest hominin occupation of Sulawesi, Indonesia[J]. Nature, 2016, 529(7585): 208-211 |

| [103] | O’Connell JF, Allen J, Williams MAJ, et al. When did Homo sapiens first reach Southeast Asia and Sahul?[J]. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 2018, 115(34): 8482-8490 |

| [104] | Clarkson C, Jacobs Z, Marwick B, et al. Human occupation of northern Australia by 65,000 years ago[J]. Nature, 2017, 547(7663): 306-310 |

| [105] | Hawkins S, O’Connor S, Maloney TR, et al. Oldest human occupation of Wallacea at Laili Cave, Timor-Leste, shows broad-spectrum foraging responses to late Pleistocene environments[J]. Quaternary Science Reviews, 2017, 171: 58-72 |

| [106] |

O’Connor S, Ono R, Clarkson C. Pelagic fishing at 42,000 years before the present and the maritime skills of modern humans[J]. Science, 2011, 334(6059): 1117-1121

doi: 10.1126/science.1207703 pmid: 22116883 |

| [107] | Park SC, Yoo DG, Lee CW, et al. Last glacial sea-level changes and paleogeography of the Korea (Tsushima) Strait[J]. Geo-Marine Letters, 2000, 20(2): 64-71 |

| [108] | Nakazawa Y. On the Pleistocene population history in the Japanese Archipelago[J]. Current anthropology, 2017, 58(S17): S539-S552 |

| [109] | Ikeya N. Maritime transport of obsidian in Japan during the Upper Palaeolithic[A]. In: Kaifu Y, Izuho M, Goebel T, Sato H, Ono A (Eds.). Emergence and Diversity of Modern Human Behavior in Paleolithic Asia[C]. Texas: Texas A&M University, 2015, 362-375 |

| [110] | Normile D. Update: Explorers successfully voyage to Japan in primitive boat in bid to unlock an ancient mystery[J]. Science, 2019. doi:10.1126/science.aay6005 |

| [111] | Fujita M, Yamasaki S, Katagiri C, et al. Advanced maritime adaptation in the western Pacific coastal region extends back to 35,000-30,000 years before present[J]. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 2016, 113(40): 11184-11189 |

| [112] | Kawamura A, Chang CH, Kawamura Y. Middle Pleistocene to Holocene mammal faunas of the Ryukyu Islands and Taiwan: An updated review incorporating results of recent research[J]. Quaternary International, 2016, 397: 117-135 |

| [113] | Détroit F, Mijares AS, Corny J, et al. A new species of Homo from the Late Pleistocene of the Philippines[J]. Nature, 2019, 568(7751): 181-186 |

| [114] | Erlandson JM, Graham MH, Bourque BJ, et al. The kelp highway hypothesis: Marine ecology, the coastal migration theory, and the peopling of the Americas[J]. The Journal of Island and Coastal Archaeology, 2007, 2(2): 161-174 |

| [115] | Erlandson JM, Braje TJ, Gill KM, et al. Ecology of the kelp highway: Did marine resources facilitate human dispersal from Northeast Asia to the Americas?[J]. The Journal of Island and Coastal Archaeology, 2015, 10(3): 392-411 |

| [116] | Bird MI, Condie SA, O’Connor S, et al. Early human settlement of Sahul was not an accident[J]. Scientific Reports, 2019, 9(1): 1-10 |

| [117] | Williams AN. A new population curve for prehistoric Australia[J]. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 2013, 280(1761): 20130486 |

| [118] | Bradshaw CJA, Ulm S, Williams AN, et al. Minimum founding populations for the first peopling of Sahul[J]. Nature ecology & evolution, 2019, 3(7): 1057-1063 |

| [119] | Pitulko VV, Tikhonov AN, Pavlova EY, et al. Early human presence in the Arctic: Evidence from 45,000-year-old mammoth remains[J]. Science, 2016, 351(6270): 260-263 |

| [120] | Pitulko VV, Pavlova EY, Nikolskiy PA. Revising the archaeological record of the Upper Pleistocene Arctic Siberia: Human dispersal and adaptations in MIS 3 and 2[J]. Quaternary Science Reviews, 2017, 165: 127-148 |

| [121] |

Pitulko VV, Nikolsky PA, Girya EY, et al. The Yana RHS site: Humans in the Arctic before the last glacial maximum[J]. Science, 2004, 303(5654): 52-56

pmid: 14704419 |

| [122] | Basilyan AE, Anisimov MA, Nikolskiy PA, et al. Wooly mammoth mass accumulation next to the Paleolithic Yana RHS site, Arctic Siberia: Its geology, age, and relation to past human activity[J]. Journal of Archaeological Science, 2011, 38(9): 2461-2474 |

| [123] | Druzhkova AS, Thalmann O, Trifonov VA, et al. Ancient DNA analysis affirms the canid from Altai as a primitive dog[J]. PloS ONE, 2013, 8(3): e57754 |

| [124] | Germonpré M, Sablin MV, Lázničková-Galetová M, et al. Palaeolithic dogs and Pleistocene wolves revisited: a reply to Morey (2014)[J]. Journal of Archaeological Science, 2015, 54: 210-216 |

| [125] | Ovodov ND, Crockford SJ, Kuzmin YV, et al. A 33,000-year-old incipient dog from the Altai Mountains of Siberia: Evidence of the earliest domestication disrupted by the Last Glacial Maximum[J]. PloS ONE, 2011, 6(7): e22821 |

| [126] | Shipman P. The Invaders: How Humans and Their Dogs Drove Neandertals to Extinction[M]. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2015, 1-263 |

| [127] | Boudadi-Maligne M, Escarguel G. A biometric re-evaluation of recent claims for Early Upper Palaeolithic wolf domestication in Eurasia[J]. Journal of Archaeological Science, 2014, 45: 80-89 |

| [128] | Janssens L, Perri A, Crombé P, et al. An evaluation of classical morphologic and morphometric parameters reported to distinguish wolves and dogs[J]. Journal of Archaeological Science: Reports, 2019, 23: 501-533 |

| [129] | Pitulko VV, Pavlova EY, Nikolskiy PA, et al. The oldest art of Eurasian Arctic[J]. Antiquity, 2012, 86: 642-659 |

| [130] | Trinkaus E, Shang H. Anatomical evidence for the antiquity of human footwear: Tianyuan and Sunghir[J]. Journal of Archaeological Science, 2008, 35(7): 1928-1933 |

| [131] | Roberts P, Boivin N, Lee-Thorp J, et al. Tropical forests and the genus Homo[J]. Evolutionary Anthropology: Issues, News, and Reviews, 2016, 25(6): 306-317 |

| [132] | Xhauflair H, Revel N, Vitales TJ, et al. What plants might potentially have been used in the forests of prehistoric Southeast Asia? An insight from the resources used nowadays by local communities in the forested highlands of Palawan Island[J]. Quaternary International, 2017, 448: 169-189 |

| [133] | Westaway KE, Louys J, Awe RD, et al. An early modern human presence in Sumatra 73,000-63,000 years ago[J]. Nature, 2017, 548(7667): 322-325 |

| [134] | Barker GWW, Barton H, Bird M, et al. The ‘human revolution’ in lowland tropical Southeast Asia: the antiquity and behavior of anatomically modern humans at Niah Cave (Sarawak, Borneo)[J]. Journal of human evolution, 2007, 52(3): 243-261 |

| [135] | Hunt CO, Gilbertson DD, Rushworth G. Modern humans in Sarawak, Malaysian Borneo, during oxygen isotope stage 3: Palaeoenvironmental evidence from the Great Cave of Niah[J]. Journal of Archaeological Science, 2007, 34(11): 1953-1969 |

| [136] | Hunt CO, Gilbertson DD, Rushworth G. A 50,000-year record of late Pleistocene tropical vegetation and human impact in lowland Borneo[J]. Quaternary Science Reviews, 2012, 37: 61-80 |

| [137] | Lewis L, Perera N, Petraglia M. First technological comparison of Southern African Howiesons Poort and South Asian Microlithic industries: An exploration of inter-regional variability in microlithic assemblages[J]. Quaternary International, 2014, 350: 7-25 |

| [138] | Roberts P, Boivin N, Petraglia M. The Sri Lankan ‘microlithic’ tradition c. 38,000 to 3,000 years ago: Tropical technologies and adaptations of Homo sapiens at the southern edge of Asia[J]. Journal of World Prehistory, 2015, 28(2): 69-112 |

| [139] |

Perera N, Kourampas N, Simpson IA, et al. People of the ancient rainforest: Late Pleistocene foragers at the Batadomba-lena rockshelter, Sri Lanka[J]. Journal of human evolution, 2011, 61(3): 254-269

doi: 10.1016/j.jhevol.2011.04.001 pmid: 21777951 |

| [140] |

Roberts P, Perera N, Wedage O, et al. Direct evidence for human reliance on rainforest resources in late Pleistocene Sri Lanka[J]. Science, 2015, 347(6227): 1246-1249

doi: 10.1126/science.aaa1230 pmid: 25766234 |

| [141] | Ji XP, Kuman K, Clarke RJ, et al. The oldest Hoabinhian technocomplex in Asia (43.5 ka) at Xiaodong rockshelter, Yunnan Province, southwest China[J]. Quaternary International, 2016, 400: 166-174 |

| [142] | Huerta-Sánchez E, Jin X, Bianba Z, et al. Altitude adaptation in Tibetans caused by introgression of Denisovan-like DNA[J]. Nature, 2014, 512(7513): 194-197 |

| [143] | Peng F, Wang HM, Gao X. Blade production of Shuidonggou Locality1 (Northwest China): a technological perspective[J]. Quaternary International, 2014, 347: 12-20 |

| [144] | Shang H, Tong HW, Zhang SQ, et al. An early modern human from Tianyuan Cave, Zhoukoudian, China[J]. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 2007, 104(16): 6573-6578 |

| [145] | Nian XM, Gao X, Xie F, et al. Chronology of the Youfang site and its implications for the emergence of microblade technology in North China[J]. Quaternary International, 2014, 347: 113-121 |

| [146] | Yi MJ, Gao X, Li F, et al. Rethinking the origin of microblade technology: a chronological and ecological perspective[J]. Quaternary International, 2016, 400: 130-139 |

| [147] | Li ZY, Ma HH. Techno-typological analysis of the microlithic assemblage at the Xuchang Man site, Lingjing, central China[J]. Quaternary International, 2016, 400: 120-129 |

| [148] | Callaway E. Evidence mounts for interbreeding bonanza in ancient human species[J]. Nature, 2016. doi:10.1038/nature.2016.19394 |

| [149] | Sankararaman S, Mallick S, Dannemann M, et al. The genomic landscape of Neanderthal ancestry in present-day humans[J]. Nature, 2014, 507(7492): 354-357 |

| [150] |

Stewart JR, Stringer CB. Human evolution out of Africa: The role of refugia and climate change[J]. Science, 2012, 335(6074): 1317-1321

doi: 10.1126/science.1215627 pmid: 22422974 |

| [151] | Dunbar RIM. The social brain: Mind, language, and society in evolutionary perspective[J]. Annual review of Anthropology, 2003: 163-181 |

| [152] | Dunbar RIM, Gamble C, Gowlett J (Ed.). Social Brains, Distributed Mind[C]. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2010 |

| [153] | Agadjanian AK, Shunkov MV. Paleolithic Man of Denisova Cave and zoogeography of Pleistocene mammals of northwestern Altai[J]. Paleontological Journal, 2018, 52(1): 66-89 |

| [154] | Olson KA, Fuller TK, Mueller T, et al. Annual movements of Mongolian gazelles: nomads in the Eastern Steppe[J]. Journal of Arid Environments, 2010, 74(11): 1435-1442 |

| [155] | Rybin EP. Tools, beads, and migrations: specific cultural traits in the Initial Upper Paleolithic of Southern Siberia and Central Asia[J]. Quaternary International, 2014, 347: 39-52 |

| [156] | Buvit I, Terry K, Izuho M, et al. The emergence of modern behaviour in the Trans-Baikal, Russia[A]. In: Kaifu Y, Izuho M, Sato H, Ono A (Eds.). Emergence and Diversity of Modern Human Behavior in Paleolithic Asia[C]. Texas: Texas A&M University Press, 2015, 490-505 |

| [157] | Graf KE, Buvit I. Human dispersal from Siberia to Beringia: Assessing a Beringian standstill in light of the archaeological evidence[J]. Current Anthropology, 2017, 58(S17): S583-S603 |

| [158] | Lbova LV. Personal ornaments as markers of social behavior, technological development and cultural phenomena in the Siberian early upper Paleolithic[J]. Quaternary International, 2021, 573: 4-13 |

| [159] | Gladyshev SA, Olsen JW, Tabarev AV, et al. Chronology and periodization of Upper Paleolithic sites in Mongolia[J]. Archaeology, Ethnology and Anthropology of Eurasia, 2010, 38(3): 33-40 |

| [160] | Gladyshev SA, Olsen JW, Tabarev AV, et al. The Upper Paleolithic of Mongolia: Recent finds and new perspectives[J]. Quaternary International, 2012, 281: 36-46 |

| [161] | Zwyns N, Gladyshev SA, Gunchinsuren B, et al. The open-air site of Tolbor 16 (Northern Mongolia): Preliminary results and perspectives[J]. Quaternary International, 2014, 347: 53-65 |

| [162] | Zwyns N, Gladyshev S, Tabarev A, et al. Mongolia:paleolithic[A]. In: Smith C (Ed.). Encyclopedia of global archaeology[C]. New York: Springer Science+Business Media, 2014, 5025-5032 |

| [163] | Kuzmin YV. Long-distance obsidian transport in prehistoric Northeast Asia[J]. Bulletin of the Indo-Pacific Prehistory Association, 2012, 32: 1-5 |

| [164] | Kuzmin YV. Obsidian as a commodity to investigate human migrations in the Upper Paleolithic, Neolithic, and Paleometal of Northeast Asia[J]. Quaternary International, 2017, 442: 5-11 |

| [165] | O’Connor S, Louys J, Kealy S, et al. Hominin dispersal and settlement east of Huxley’s Line: The role of sea level changes, island size, and subsistence behavior[J]. Current Anthropology, 2017, 58(S17): S567-S582 |

| [166] | Piper PJ, Ochoa J, Robles EC, et al. Palaeozoology of Palawan Island, Philippines[J]. Quaternary International, 2011, 233(2): 142-158 |

| [167] | Kealy S, Louys J, O’Connor S. Reconstructing palaeogeography and inter-island visibility in the Wallacean Archipelago during the likely period of Sahul colonization, 65-45000 years ago[J]. Archaeological Prospection, 2017, 24(3): 259-272 |

| [1] | 惠家明. 颅骨板障静脉的三维复原及其在人类演化中的意义[J]. 人类学学报, 2025, 44(04): 545-555. |

| [2] | 邓婉文, 谢颖. 广西隆安娅怀洞遗址发现的小型石制品[J]. 人类学学报, 2025, 44(03): 413-426. |

| [3] | 华杰群, 葛俊逸, 陆成秋, 沈中山, 邢松, 卢泽基, 高星, 邓成龙. 湖北郧县学堂梁子古人类遗址年代学研究进展[J]. 人类学学报, 2025, 44(02): 316-332. |

| [4] | 张亚盟, 吴秀杰. 中国晚更新世早期现代人内耳迷路的形态变异[J]. 人类学学报, 2024, 43(06): 1038-1047. |

| [5] | 关莹, 王社江, 周振宇, 高星, 张茜. 洛南手斧上的淀粉粒与古人类使用石器的策略[J]. 人类学学报, 2024, 43(06): 1064-1074. |

| [6] | 李锋. 早期现代人向东亚扩散北方路线的研究进展与展望[J]. 人类学学报, 2024, 43(06): 951-966. |

| [7] | 魏偏偏, 赵昱浩. 东亚地区更新世古人类股骨的演化[J]. 人类学学报, 2024, 43(06): 993-1005. |

| [8] | 周亚威, 王煜, 侯晓刚, 李树云. 山西大同金茂园遗址人群颅骨的形态学[J]. 人类学学报, 2024, 43(02): 233-246. |

| [9] | 吴秀杰. 中更新世晚期许家窑人化石的研究进展[J]. 人类学学报, 2024, 43(01): 5-18. |

| [10] | 倪喜军. 人类起源研究中的哲学问题[J]. 人类学学报, 2023, 42(06): 709-720. |

| [11] | Omry BARZILAI. 以色列内盖夫沙漠的发现对黎凡特石器工业来源与去向的启示[J]. 人类学学报, 2023, 42(05): 626-637. |

| [12] | 贺乐天, 王永强, 魏文斌. 新疆哈密拉甫却克墓地人的颅面部测量学特征[J]. 人类学学报, 2022, 41(06): 1017-1027. |

| [13] | 刘鑫, 张兴华, 宇克莉, 刘艳霞, 包金萍, 郑连斌. 生物电阻抗法测定广西京族的体成分[J]. 人类学学报, 2022, 41(06): 1028-1036. |

| [14] | 沙仁高娃, 程慧珍, 韦兰海. 达斡尔语分支早期在蒙古语族中的地位[J]. 人类学学报, 2022, 41(06): 1037-1046. |

| [15] | 邢松. 现代人出现和演化的化石证据[J]. 人类学学报, 2022, 41(06): 1069-1082. |

| 阅读次数 | ||||||

|

全文 |

|

|||||

|

摘要 |

|

|||||

京ICP证05002819号-3

京ICP证05002819号-3